Women's Long Journey for the Vote

by Eleanor Clift

The earliest and most famous expression of the discontent American women felt over their station in life was voiced by Abigail Adams in March 1776 when she urged her husband, the future president John Adams, to “Remember the Ladies, & be more generous & favourable to them than your ancestors.” John Adams was meeting with the Continental Congress in Philadelphia, drafting a new code of laws that, his wife warned him, women would not feel bound to obey if they had no voice or representation.

Three-quarters of a century later, on the morning of July 19, 1848, more than three hundred people streamed into the Wesleyan Chapel in Seneca Falls, New York, for what was billed as a “Woman’s Rights Convention.” Local newspapers dubbed it “The Hen Convention,” and one writer described the participants as “divorced wives, childless women and some old maids.”

Elizabeth Cady Stanton, a noted abolitionist and the daughter of a lawyer and judge, read aloud a Declaration of Sentiments that she had drafted. Modeled after the Declaration of Independence, it became the road map for women’s rights, addressing a host of inequalities and demanding voting rights for women, without which none of the other rights could flow.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton, a noted abolitionist and the daughter of a lawyer and judge, read aloud a Declaration of Sentiments that she had drafted. Modeled after the Declaration of Independence, it became the road map for women’s rights, addressing a host of inequalities and demanding voting rights for women, without which none of the other rights could flow.

History regards Seneca Falls as the official kickoff of the suffrage movement, and Stanton as its muse. Housebound with several young children, her outlet was writing speeches for Susan B. Anthony, a devoted suffragist unencumbered by marriage and children and able to travel the country spreading the word.

Their friendship and partnership endured through all the ups and downs of the decades-long suffrage movement, but they didn’t live long enough to see the result of their years of labor.

Fast forward to the March 1913 in Washington DC, when some eight thousand women from all walks of life gathered to march in support of suffrage. When President-elect Woodrow Wilson arrived at Union Station the afternoon before his inauguration, then held in March and not January as it is today, he wondered aloud where the crowds were to greet him. He was told they were over on Pennsylvania Avenue to watch the women.

There were women in nurse’s uniforms, college women in their academic robes, and working women in their everyday clothes. At the head of the parade, there was a strikingly beautiful woman named Inez Milholland riding a white horse and carrying a banner of purple, white and gold—suffrage colors, purple for the royal glory of women, white for purity, and gold for the crown of the victor.

The New York Times called it “one of the most impressively beautiful spectacles ever staged in this country.”

It was also the first time a protest had marred a presidential inauguration, and along the avenue the sidewalks were lined with men who were not happy with what they were seeing. They heckled and jeered the women and then, as the police stood by and did nothing, they stormed the marchers, making it impossible for the parade to continue, tripping and shoving the women, spitting on them, and tossing lighted cigarette butts at them.

A hundred women were taken to the hospital, and the Chicago Tribune reported that Helen Keller, famous for having overcome deafness and blindness to become a voice for women, “was so exhausted and unnerved by the experience” of having to reach a grandstand to find safety that she was unable to speak that evening at Constitution Hall.

It was a full-blown scandal, and there were congressional hearings during which more than 150 witnesses described the melee. The chief of police in the District of Columbia lost his job, and, after a long period of inactivity, the suffrage cause was jolted back into the headlines with a new young vibrant leader named Alice Paul.

Paul had a master’s degree in political science and sociology from the University of Pennsylvania when she headed to England in 1907 to further her studies. There she was exposed to more radical forms of protest as British suffragists stormed Parliament and lay down in streets to impede traffic. Paul was arrested and jailed for a short period of time before returning to the United States in 1910, determined to import British tactics and shake the US suffrage movement out of its complacency.

Paul had a master’s degree in political science and sociology from the University of Pennsylvania when she headed to England in 1907 to further her studies. There she was exposed to more radical forms of protest as British suffragists stormed Parliament and lay down in streets to impede traffic. Paul was arrested and jailed for a short period of time before returning to the United States in 1910, determined to import British tactics and shake the US suffrage movement out of its complacency.

While she would never condone violence, Paul recognized that the violence at the Inaugural protest helped the suffrage cause. The New York Tribune headline declared, “Capital Mobs Make Converts to Suffrage.”

Building on that sympathy, and upping the pressure, Paul organized rotations of women, known as “Silent Sentinels,” to stand outside the White House gate every day except Sunday to protest for the vote. President Wilson would come through the gate in his carriage with his wife, tip his hat to the women, and assume that once it got cold they would disperse.

He was wrong. When the frigid weather set in, the women brought in heated bricks to stand on, defying Wilson’s expectation that they would wilt under trying conditions. These were well-connected women, and Paul made sure that their activities were well publicized. Some had husbands who knew Wilson well, so pressure was applied from all sides.

With the clouds of World War I gathering, Wilson felt besieged by the suffragists, and in a fit of exasperation, he ordered them arrested for loitering in a public space. They received sentences of up to sixty days at Virginia’s Occoquan Workhouse, where they were housed with common criminals, and alongside black women—an offense in the segregated South—and subsisted on substandard food infested with vermin. The women wrote notes describing their treatment and stuck them through holes in the workhouse wall, allowing Paul to circulate them to the public.

The public was shocked to learn that the White House would subject women to such horrific conditions. Wilson responded by issuing a blanket pardon for all the women arrested, thinking that would put an end to the matter.

He was wrong again. The women kept returning to picket, until finally Alice Paul herself was taken into custody and sentenced to seven months in jail. Her mental health was evaluated and she was seen to have “an unhealthy obsession” with President Wilson. Paul remained unbowed, and when she and thirty others went on a hunger strike, they were force-fed in a particularly brutal way. (The HBO movie, Iron Jawed Angels, with Hillary Swank playing Paul, takes its name from the metal clamp forcing open Paul’s mouth as raw eggs were poured down a tube into her stomach.)

On November 27 and 28, 1917, Alice Paul and twenty-one other suffrage prisoners were released, and on January 10, 1918, the House by one vote approved the Susan B. Anthony Amendment.  What women had been through to make their case had moved the House, but not the Senate, where the Amendment failed even though Wilson argued passionately for it, declaring that women’s role in supporting the country during World War I had earned them the vote.

What women had been through to make their case had moved the House, but not the Senate, where the Amendment failed even though Wilson argued passionately for it, declaring that women’s role in supporting the country during World War I had earned them the vote.

Republicans won majorities in the House and Senate in November 1918, and Wilson, recognizing the momentum of the suffrage movement, requested the new Congress meet early in a special session. The Nineteenth Amendment passed the House handily and by two votes in the Senate.

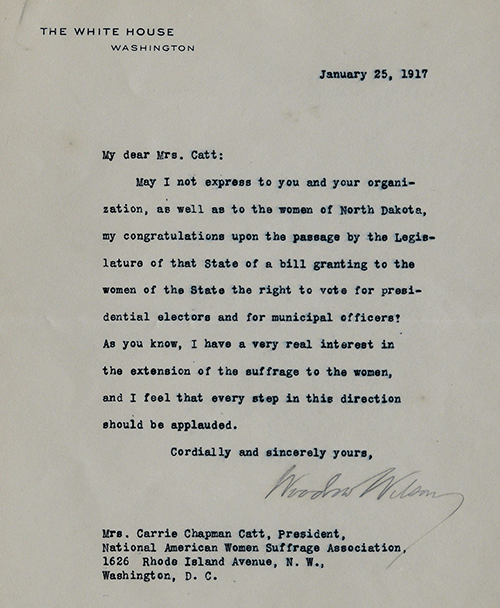

The fight then moved to the states where two-thirds, or 36 states, were needed for ratification. Alice Paul had gotten the amendment this far with her bold tactics and marketing savvy. Now the challenge was nuts-and-bolts organizing, and there was no one more capable than Carrie Chapman Catt. A generation older than Paul, Catt disapproved of Paul’s “barbarian” tactics, but they had worked, and now the hard-nosed organizing to get the amendment over the finish line fell to her.

It came down to Tennessee and a young legislator named Harry Burn whose mother was watching to see what he would do. She knew that his constituents in their rural community of Mouse Creek were opposed, so she sent him a telegram saying, “Don’t forget to be a good boy and help Mrs. Catt put the ‘rat’ in ratification.” (A popular cartoon showed a woman with a broom sweeping away the letters.)

There was still plenty of drama as Burn initially voted against suffrage, then switched his vote, leading to various theories about whether he might have accepted a bribe. Years later, he said simply that once he realized he was going on record for all time on the merits of the question, he had to vote for ratification.

Getting the vote was exhilarating, but once the battle was won, women took this new right for granted. Voting rates dropped, prompting Catt to despair before she died in 1947. In November 1920, she wrote, “Women have suffered an agony of soul which you can never comprehend, that you and your daughters might inherit political freedom. That vote has been costly. Prize it.”

Eleanor Clift is a columnist for the Daily Beast. She writes about politics and policy in Washington, and has covered every presidential campaign since 1976. She is best known as a panelist on the syndicated talk show The McLaughlin Group, which ended in 2016. Her book, Founding Sisters and the Nineteenth Amendment, was published by John Wiley & Sons in 2003.