Understanding the Burr-Hamilton Duel

by Joanne B. Freeman

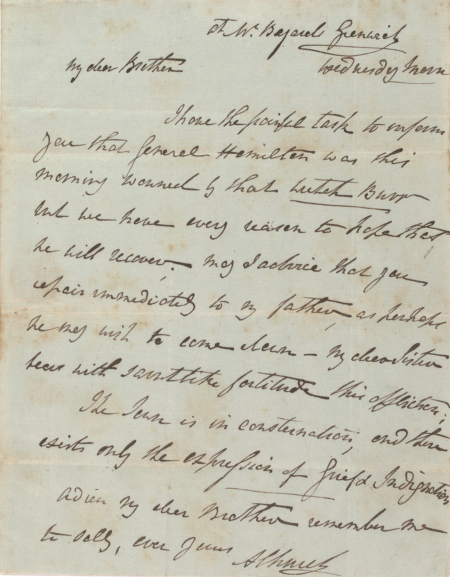

Without a doubt, the duel between former Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton and Vice President Aaron Burr is the most famous duel in American history. On July 11, 1804, the two political rivals met on a dueling ground in Weehawken, New Jersey. Hamilton’s shot went high—perhaps deliberately, perhaps not. Burr’s shot hit Hamilton in his abdomen, pierced his liver, and lodged in his spine. He died the next day.

Deadly, dramatic, and featuring two major-league Founders, the Burr-Hamilton duel is famous for good reason. But it is also misunderstood, largely because the practice of dueling makes little sense from the distance of two centuries. What could drive two rational and intelligent men to willingly risk their lives in a deadly showdown that seemingly accomplished nothing? Searching for answers, many twenty-first-century onlookers attribute the Burr-Hamilton duel to raging emotions or a hankering for revenge, viewing Burr as a fiendish killer and Hamilton as a suicidal martyr.

Yet Burr and Hamilton weren’t the period’s only duelists. Hundreds of men faced each other on the field of honor in early America, and most of these men weren’t fiends or martyrs. They fought duels because dueling made sense to them.

It certainly made sense to Burr and Hamilton. Like many politicians, they chose to fight a duel for good reasons. To understand those reasons, we need to take a closer look at the Burr-Hamilton duel.

What caused the Burr-Hamilton duel?

This question has two answers. The short answer involves an election and an insult. In 1804, Burr ran for governor of New York and lost the election, due in part to Hamilton’s ardent opposition; by this point, the two men had been political rivals for fifteen years. So when a friend showed Burr some of Hamilton’s nasty charges in a newspaper clipping—providing written proof of Hamilton’s insults—Burr acted.

The long answer involves the nuts and bolts of politics in early national America. Sometimes, when politicians lost elections, they initiated duels to redeem their reputation and prove themselves worthy political leaders. In New York City alone, between 1795 and 1807 there were sixteen duels and near-duels, most of them tied to elections. Typically, the loser of an election or one of his friends provoked a duel with the winner or one of his friends in the hope of proving the losers brave and honorable men who deserved the public trust. In essence, some politicians—like Burr—used an aristocratic practice to repair the damage to their reputation wrought by a democratic election. Having suffered the humiliation of losing New York’s gubernatorial election, Burr provoked a duel with Hamilton to prove himself a worthy leader who deserved public support and could offer his followers political offices and gains in the future.

Was Burr trying to kill Hamilton?

Probably not. As illogical as it may seem, many political duelists in this period didn’t want to kill their opponents. The point of a political duel was to prove a man willing to die for his honor, not to shed blood. Thus the many near-duels—"affairs of honor"—that were settled through negotiations: eleven of the sixteen affairs of honor in New York City were settled in this manner. Only five honor disputes resulted in a duel.

The negotiation process was highly ritualized. At the outset of most honor disputes, an offended man would write a carefully phrased letter to his attacker demanding an explanation. From that point on, the two men would communicate through letters delivered by friends—known as "seconds"—who tried to negotiate an apology that appeased everyone and dishonored no one. In many cases, the seconds were successful, and there matters ended. Upon receiving Burr’s initial letter of inquiry, Hamilton may well have expected little more than a ritualized exchange of letters, particularly given that before 1804, Hamilton had been involved in ten such bloodless honor disputes.

But sometimes, an insulted man felt so wounded that only a life-threatening exchange of fire could repair the damage. In such cases, he would force his opponent to duel by demanding an apology so extreme that no honorable man could concede to it. Burr did this when his negotiations with Hamilton went awry and spawned new insults. Feeling profoundly dishonored and desperate for a chance to redeem his name, Burr demanded that Hamilton apologize for all of his insults throughout their fifteen-year rivalry. Predictably, Hamilton refused, Burr challenged him to a duel, Hamilton accepted the challenge, and their seconds began planning their pending "interview" in Weehawken.

Even at this point, knowing that he would soon face Hamilton on the field of honor, Burr probably wasn’t eager to kill him. For political duelists, killing their opponent often did more harm than good, making them seem bloodthirsty, opening them to attack by their opponents, and making them liable for arrest. Burr suffered this fate after killing Hamilton. Political opponents accused him of being a dishonorable, merciless killer (insisting, for example, that he was wearing a bullet-proof silk coat during the duel, and that he laughed as he left the dueling ground). He was charged with murder in New Jersey and New York. With the public turned against him and criminal charges pending, Burr—the Vice President of the United States—fled to South Carolina and went into hiding.

Was Hamilton trying to commit suicide by fighting a duel?

Again, probably not. There’s no denying that Hamilton was in low spirits in 1804. His political career was in decline. His political enemies, the Jeffersonian Republicans, were in power and seemed likely to stay there. And his oldest son Philip had died in a duel defending his father’s name three years past. Hamilton had reason to feel depressed. But given that deaths were relatively uncommon in political duels, it is highly unlikely that he was trying to kill himself by accepting Burr’s challenge. He had no reason to assume that he would die.

In fact, by Hamilton’s logic, not accepting Burr’s challenge may have seemed suicidal; by dishonoring himself, he would have destroyed his reputation and career. Several years earlier, when war with France was looming, Hamilton had used similar logic when discussing national honor. Urging Americans to denounce French insults and injuries, Hamilton argued that abandoning national honor would be "an act of political suicide." Surrendering one’s honor and accepting disgrace—not fighting—would be suicidal.

Why didn’t Hamilton decline Burr’s challenge? Why didn’t he just say no?

Hamilton’s decision to accept Burr’s challenge is particularly difficult to understand. Dueling was illegal, unpopular, and for many, irreligious. On all three counts, couldn’t Hamilton have simply refused to fight?

For Hamilton, the answer was no, and he explained his reasoning in a four-page statement to be made public only in the event of his death. He didn’t want to fight Burr, he admitted, and for good reason: dueling violated his religious and moral principles, defied the law, threatened the welfare of his family, put his creditors at risk, and ultimately compelled him to "hazard much, and . . . possibly gain nothing." But by Hamilton’s logic, the duel seemed impossible to avoid. He couldn’t apologize for his insults, because he meant them. And during their negotiations, Hamilton and Burr had exchanged harsh words, making a duel near unavoidable. Equally important, Hamilton was thinking about his future—yet another reason to doubt that he was suicidal. Had he refused to duel, he explained, he would have been dishonored and thereby unable to assume a position of leadership during future crises in public affairs. To preserve his reputation as a leader, he had to accept Burr’s challenge.

Why wasn’t Burr arrested?

Formally speaking, Burr could have been arrested on several counts. Dueling was illegal in most states, as was sending or receiving a duel challenge. And Burr had murdered Hamilton. Yet, although Burr was charged with murder in New York and New Jersey, he was never punished. In part, this was a product of his elite status. Leaders and elite gentlemen were rarely punished for dueling, even though they themselves passed anti-dueling laws; their privileged status often put them above the law. When New Jersey persisted in charging Burr with murder, eleven of Burr’s political allies in Congress defended his elite privilege in print, petitioning New Jersey’s governor to remind him that most political duels weren’t prosecuted, and that "most civilized nations" didn’t consider dueling fatalities "common murders."

What happened to Burr?

Burr’s eventful life became more tangled after his duel with Hamilton. After hiding in South Carolina for a time, he returned to Washington to resume his responsibilities as vice president. Many of Hamilton’s fellow Federalists in the Senate were horrified: Hamilton’s murderer was their presiding officer. In 1805, ousted from the Vice Presidency after President Jefferson’s first term, and having destroyed his career in both national and New York State politics, Burr turned his gaze west, heading towards Mexico with a small band of men, his intentions unclear. But the Jefferson administration felt sure that he was planning something treasonous, perhaps plotting a revolution to separate western states from the Union. Tried for treason in 1807, Burr was acquitted and fled to Europe, where he remained in self-imposed exile until 1812, when he returned to New York and resumed his law practice, deeply in debt. He died on September 14, 1836.

Did the Burr-Hamilton duel end dueling in America?

No, though it helped. Hamilton’s death launched an outcry of anti-dueling sentiment. North and South, religious and social reformers seized the moment to denounce dueling and demand the enforcement of anti-dueling laws. Dueling was already in decline in the North, and Hamilton’s death likely furthered its fall. But it lingered in the North and continued to thrive in the South long after 1804. Increasingly viewed as a Southern practice, it died a slow death throughout the first half of the nineteenth century, with elite politicians using it to their advantage until its demise.

Joanne B. Freeman, Professor of History and American Studies at Yale University, has written extensively on American politics in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Her book Affairs of Honor: National Politics in the New Republic (Yale University Press, 2002) won the Best Book award from the Society of Historians of the Early American Republic. She is the editor of Alexander Hamilton: Writings (Library of America, 2001).