"The Authentic Voice of Today": Lin-Manuel Miranda's Hamilton

by Elizabeth L. Wollman

"The show is the first Broadway musical in some time to have the authentic voice of today rather than the day before yesterday."

The comment above could easily have been written about Hamilton, but it was written long before Hamilton’s composer, lyricist, book-writer, and current star, Lin-Manuel Miranda, was even born. It’s from 1968, and it appeared in the New York Times review by theater critic Clive Barnes of Broadway’s first hit rock musical, Hair. Like Hamilton, Hair was one of the most commercially and critically successful, aesthetically influential Broadway musicals to open in a very, very long time. Like Hamilton, Hair accomplished what most people thought was impossible, in blending Broadway show tunes with contemporary pop music without sounding horrible. And like Hamilton, Hair was tough to get tickets to for a while.

While their reception histories and their use of pop music are similar, these musicals don’t otherwise initially seem to have much in common. Hair, about a group of hippies in Greenwich Village, was loosely plotted and employed lots of experimental techniques to examine the Civil Rights Movement, the Vietnam War, the counterculture, the generation gap, and other contemporary issues. Characters frequently broke the imaginary fourth wall to wander through the aisles or address the audience directly, did or said things that were meant to be more symbolic than realistic, and at one much-talked-about point, stripped completely naked (albeit in very dim light).

No one gets naked in Hamilton, which uses comparatively little in the way of experimental direction or performance. Hamilton refers regularly to the contemporary United States, but it is rooted in the distant past, and its sociopolitical commentary is thus less obvious than Hair’s was. Also unlike Hair, Hamilton is tightly plotted, with a clear beginning (Hamilton emigrates from the West Indies and makes new friends in New York), middle (Hamilton and his friends fight in the Revolutionary War, start families, and set about establishing an independent nation), and end (Hamilton is mortally wounded during a duel with Aaron Burr).

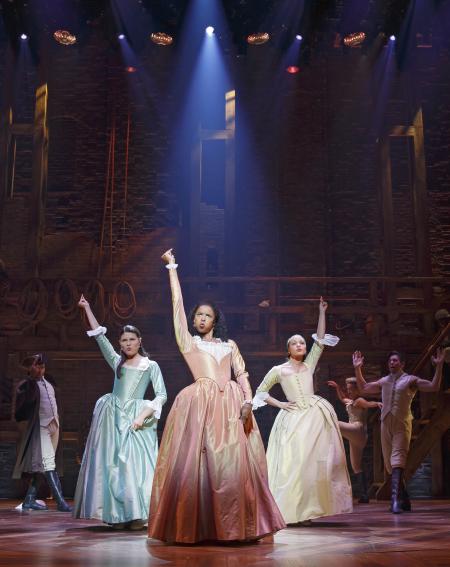

Hamilton thus seems more conventional and accessible than Hair did in its day. Its approach to its subject matter is meant to unite, not divide. While Hair offended plenty of conservatives, Hamilton gently reaches across the aisle. Despite Hamilton’s unhappy demise, Hamilton is also unflaggingly optimistic in depicting him as the embodiment of the American dream: he is a "young, scrappy, and hungry" immigrant whose motto is "I am not throwing away my shot!" Like countless model Americans to follow him, Hamilton seizes every opportunity he is given, works hard, and earns respect and status in exchange. Driving this message home is the show’s casting. While the historical figures being depicted were Caucasian, Hamilton’s cast features almost entirely actors of color, whose performances link America’s past to its dizzyingly diverse present.

If you get past the major differences, it is easier to see how much Hair and Hamilton have in common. Both were initially nurtured and produced Off Broadway at the Public Theater, the mission of which is to create challenging, accessible theater that speaks to cultural, social, or political issues. Both depict young Americans who love their country and are passionate about supporting or protesting its policies. Both shows feature diverse casts and appeal to spectators who otherwise don’t feel especially at home or included on Broadway. And both have enormously catchy, innovative scores that have the "voice of today rather than the day before yesterday."

Shows that become as monumentally successful as Hair or Hamilton are exceedingly rare, for a number of reasons. First, Broadway musicals are famously risky ventures. Of course, the payoff can be enormous for a hit: in 2014, for example, Variety reported that the musical version of The Lion King, which opened on Broadway in 1997, had become the top box office title in any medium, with worldwide earnings of $6.2 billion. But most Broadway musicals—approximately 80 percent of them—don’t run for long enough to make back their primary investments.

Second, Broadway has a lot more competition than it did back when there were no movies, television, or Internet. They are expensive, and a lot of people think they are corny and outdated. It doesn’t help that Broadway historically caters to its core audience—white, middle-class, middle-aged people. This is why musicals like Hair and Hamilton are so important: they remind everyone that the musical theater—a genre, after all, that was born and bred in the US—can and should be original, accessible, and representative of people from all backgrounds.

Inclusiveness and accessibility are clearly important to Miranda, and are reflected in many ways in Hamilton. Much like Alexander Hamilton himself, Miranda is clearly so fascinated with and passionate about something that he has been unable to keep from inserting himself into it, messing around with its guts enough to leave an indelible mark. Hamilton loved his adopted country so much that he poured his energy into it, tinkering endlessly with the details of its foundation in hopes of ensuring its best possible future. Miranda, too, has worked obsessively to innovate and help ensure the continued relevance of one of the country’s major performing arts genres. The American musical won’t be the same as a result of his attention to it.

While critics and historians have been quick with Hamilton, as they were with Hair, to apply the word "revolutionary," the term isn’t fair to either production. "Revolutionary" implies total, unprecedented change, but no musical—no art—emerges from nowhere to change everything in its path. Like Hair, Hamilton harnesses the past to the present and is thus brilliantly evolutionary. In uniting Rodgers and Hammerstein with Biggie Smalls, Cab Calloway with Jay-Z, and Gilbert and Sullivan with DMX, Hamilton pushes the stage musical forward while never forgetting where it came from. It’s no invading alien: Hamilton fits on Broadway the way Alexander Hamilton fit in New York.

Of course, in linking past with present, Hamilton inevitably takes risks in some ways and remains pretty traditional in others. Slavery is openly denounced in Hamilton, and the casting choices certainly speak for themselves. Yet there is no representation of people of color who lived during the colonial era and in some way or another served the Revolution. The slave Cato, for example, along with his owner, Hercules Mulligan, acted as a patriot spy and courier during the war. While Mulligan’s heroic actions are celebrated in the musical, there is no mention of Cato or other blacks who lived and worked—either as free or enslaved people—during the time.

Miranda clearly tried to give voice to the women of the revolutionary generation—even allowing Eliza Hamilton the final words of the musical—but Hamilton doesn’t attempt to challenge the gender codes and assumptions buried deep in traditional narratives or contemporary commercial staging. The plot places primary focus on the important work men did in building the country, while the female characters are ultimately secondary to the action. The hip-hop styles used in the score are an enormous revelation, but gender codes remain firmly rooted in the use of contemporary styles, too: the rap battles are performed by men at their most swaggeringly macho; female characters tend instead to sing songs based in gentler, smoother (and more female-identified) R&B stylings of solo singers like Beyoncé or groups like TLC.

Then again, a century ago, Broadway audiences were segregated (until the early 1920s, whites sat in the orchestra and blacks in the balcony). Black performers were paid less and were highly restricted in terms of what they could do onstage. Today, actors of color believably depict the founding fathers using contemporary music rooted in black American culture, and in doing so are luring spectators of all ideologies, ages, and backgrounds to Broadway—and turning them on to hip-hop and American history in the process. For all the lengths we need to go when it comes to race and representation, we’ve nevertheless come a very long way. Hamilton reminds us of and celebrates that fact. Like this country, after all, Hamilton was made by immigrants, who, the show reminds us, "get the job done." It doesn’t take a revolution to drive that point home—just a great show with a great score and a message that everyone is welcome at the table.

Elizabeth L. Wollman is on the faculty of the Department of Fine and Performing Arts at Baruch College. Her scholarly interests include the history of the Broadway musical since 1980, American popular music, gender studies, and aesthetics. She is the author of Hard Times: The Adult Musical in 1970s New York City (Oxford University Press, 2013) and The Theater Will Rock: A History of the Rock Musical, From Hair to Hedwig (University of Michigan Press, 2006).