Sylvester Graham and Antebellum Diet Reform

by Cindy Lobel

"Eat Food. Not too much. Mostly Plants." So begins Michael Pollan’s 2009 book, In Defense of Food. Pollan has made a career educating Americans about the dangers of our contemporary, industrialized food supply. His book offers a manifesto in defense of "real food – the sort of food our great grandmothers would recognize as food," removed from industrial processes and professional nutrition advice. Pollan’s writings on the contemporary food supply are very much of our time, but his concerns are not entirely new. If we were to put him to the test and return to the time of our grandmothers’ grandmothers, he would hear arguments about the food supply that presage his own.

"Eat Food. Not too much. Mostly Plants." So begins Michael Pollan’s 2009 book, In Defense of Food. Pollan has made a career educating Americans about the dangers of our contemporary, industrialized food supply. His book offers a manifesto in defense of "real food – the sort of food our great grandmothers would recognize as food," removed from industrial processes and professional nutrition advice. Pollan’s writings on the contemporary food supply are very much of our time, but his concerns are not entirely new. If we were to put him to the test and return to the time of our grandmothers’ grandmothers, he would hear arguments about the food supply that presage his own.

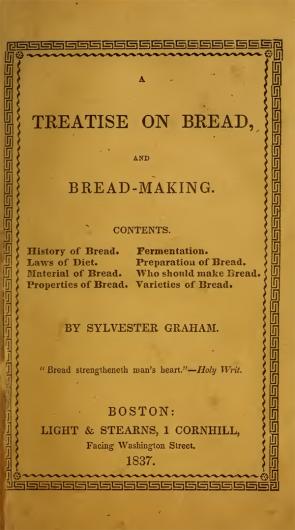

In the 1830s, critiques of American food and eating were rampant and shrill, and usually attached to the name of Sylvester Graham, the de facto founder of the diet reform movement in the antebellum United States. During the 1830s and 1840s, the man Ralph Waldo Emerson described as the "prophet of bran bread" made a name for himself lecturing and publishing books on diet and proper living. Graham developed a system of healthy living that eschewed strong drink and overly processed food, and advocated moderation in all areas of daily life. Graham and his followers posited a strong link between diet, health, and morality, seeing the body as a holistic system that needed to be kept in balance in order for the individual to maintain physical and spiritual health. Graham gave his name to a movement and those who followed any of his tenets became known as "Grahamites."

Few Americans today know who Sylvester Graham is, or realize that they memorialize him in some small way every time they eat a Graham cracker—an adulterated form of the bran bread that was central to Graham’s system. But Graham’s impact was strongly felt in nineteenth-century America. In the antebellum decades, many individuals became Grahamites, limiting their diets; avoiding meat, spices, condiments, and complex preparations of food; abstaining from alcohol; and bathing regularly.

Graham’s followers established boardinghouses in various cities across the country where Grahamites could stay and take their meals while traveling. They opened provisions stores to supply pure, healthy foodstuffs. They published a magazine, the Graham Journal of Health and Longevity, and numerous books; established physiological societies in cities like Boston and New York and on college campuses like Oberlin, Wesleyan, and Williams; and held a number of health conventions. By the Civil War, Graham’s tenets and theories had influenced even more-widespread health crusades, such as the water-cure movement, which used various water treatments to cure disease and maintain health, and phrenology, the pseudoscientific movement that attributed character traits and conduct to the physical shape and size of the skull. New religious movements like Christian Science and Seventh-day Adventism incorporated Grahamite principles. And following the Civil War, entrepreneurs like the cereal mavens the Kellogg brothers integrated the Grahamites’ concerns into the marketing of their commercial products.

The diet reform movement influenced many Americans who did not consider themselves Grahamites. Nineteenth-century manuscript and published cookbooks included recipes for Graham bread, Protestant ministers offered sermons on the connection between diet and morality, and advice books urged healthy living based on Grahamite principles. In short, the ideas and values of the diet reform movement as initiated by Graham became part of mainstream American culture in the nineteenth century and beyond.

While he frequently insisted that his theories were novel and original, Graham was hardly the first individual to advocate a regimented diet, or to draw connections between diet and character. But Graham was the first diet reformer in the United States to give his name to a movement. So why did Graham and his followers make such a splash when they did, leading one journalist to fear that "this wild Fanaticism will sweep through the land overthrowing every social comfort, every physical enjoyment, every pleasure that springs from sense and refers to sense"?[1]

As with all historical phenomena, context is important. In order to understand diet reform’s appeal, one must understand the time and place in which the diet reformers lived and worked. Part of Graham’s influence sprang from his access to a mass audience. Quite simply, Graham reached more Americans than any of his predecessors because he had greater access to them. Technological innovations like the steam press and new distribution techniques brought about an explosion in printed material—reformers’ tracts, advice literature, newspapers, magazines, and books of all kinds. Lectures became a common form of middle-class entertainment in the nineteenth century and lyceums and theaters emerged in all American cities to host them. Diet reformers thus stood on a soapbox of unprecedented height.

Diet reform also must be understood within the general reform ferment that spread through the United States in the early nineteenth century. Indeed, these movements shared many of the same adherents and the same influences. Temperance, abolitionism, diet reform, and other movements were rooted in the Second Great Awakening, a series of millennialist religious revivals that swept through the United States in the early nineteenth century. According to the converted, Christ’s Second Coming, and the thousand-year period described in Revelation, was imminent and Americans had to perfect themselves to be prepared for its arrival. This notion of perfectionism—and the potential for achieving it—was at the root of most of the reform movements of the nineteenth century, and diet reform was no exception.

One cannot separate the nineteenth-century diet reformers’ program and philosophies from their moralistic underpinnings. Sylvester Graham and many of his allies were ordained ministers who posited strong connections between diet, character, and morality. William Andrus Alcott, another important health reformer of the time, claimed that you could judge a child’s character by his eating habits.

Graham’s position on diet also was linked inextricably to his stance on sexuality. He believed that the body needed to be kept in balance to be healthy. If one area became overstimulated in any way, the whole system would deteriorate. In addition to sexuality and the vices of the day, heat itself was overstimulating. So Graham claimed that featherbeds encouraged sexual activity and argued that all food, even the healthiest, should never be eaten hot.

Graham lectured not only on food but also on chastity, delivering and publishing a famous lecture series to young men on sexuality. And Graham and his disciples made strong connections between certain stimulating foods—including spices, coffee, meat, and alcohol—and various vices. Eat spicy foods, they argued, and you might have a spicy constitution, making you prone to the temptations of the day, including drinking, gambling, and prostitution. Graham argued that gluttony was not only unhealthy but also immoral, asserting that eating to excess "is one of the greatest sources of evil to the human family."[2]

Today (as in Graham’s time), some of this advice appears downright peculiar, seeming to justify Graham’s reputation as a quack and a humbug and that of his followers as "cranium cracked dyspeptics."[3] But many tenets of diet reform sound quite reasonable to modern readers. Grahamites tried to eat less meat and more fruit and vegetables, to avoid very rich foods, to practice moderation in diet, to avoid processed foods, and to enjoy fresh air and exercise. Even the centerpiece of Graham’s dietary system—insistence on whole grain breads rather than those made with refined flours—makes sense to today’s consumers.

In fact, the diet reformers may have had appeal in the nineteenth century because American eating habits were, in fact, unhealthy. The standards of the antebellum diet included greasy foods, a surfeit of meat, and very limited fruits and vegetables. In fact, many medical experts argued that fruits and vegetables were unhealthy, particularly in an unprocessed state. Americans were known for eating too much and for "the voracious rapidity with which the viands were seized and devoured," as notorious British visitor Frances Trollope observed.[4] The growing cities had inadequate water supplies, overcrowded neighborhoods, and poor sanitation, leading to epidemic rates of digestive disease and discomfort and extraordinarily high mortality rates. It is no wonder that the dyspeptic businessman was as common an archetype of Victorian America as the fainting lady.

Early nineteenth-century medical practices were likewise unhealthy. Traditional medical practitioners embraced long-standing heroic measures such as leeching, bloodletting, blistering, and the use of opiates and other debilitating drugs to cure disease. Homeopaths, water curists, and Thomsonians developed preventives and cures for disease that eschewed invasive cures in favor of gentler and more holistic approaches. Thomsonians, for example, relied on herbs and regulating body temperatures and water curists used various water treatments to cure disease and maintain health. Diet reform was part of this larger health reform movement.

Diet reform also offered a program for making sense of the massive changes to American society during the market and industrial revolutions of the nineteenth century as the United States evolved from an agrarian to an industrial society. A subsistence-plus economy where households produced a good deal of their own food and household goods yielded to a commercial economy in most of the United States. Increasingly, households purchased daily necessities, sometimes from distant producers. Cities were growing and becoming more influential, and more Americans were migrating to urban areas to seek employment as the land ceased to offer opportunities to farmers’ sons and daughters. The antebellum cities offered a host of commercial entertainments and sensual lures including gambling dens, brothels, and theaters. According to ministers and reformers concerned about urban morals, even seemingly innocent outlets like restaurants, oyster cellars, and ice creameries could lead one into temptations and vice.

The diet reformers insisted that one could maintain physical and spiritual health by eschewing processed foods and complex preparations, and by avoiding the commercial lures of the burgeoning city. Graham’s bread itself reflected a resistance to industrial, commercial society. Graham argued that the commercial practice of removing the outer layer (bran) from the wheat removed all nutritious matter from bread, with dire consequences for health and morality. He attacked commercial bakers, arguing that even if they used unrefined flour, their primary goal was still profit, rather than the health of their customers, and so they created an inherently unsound product. The only fit bread, he concluded, was that made in the home by the mother and wife, who infused her bread with love and care. Graham decried commercial flours and breadstuffs at a time when most urban women were growing reliant on these modern products. Hearkening back to an idealized vision of self-reliance and home production, Graham assured his followers that they could maintain personal and societal health by avoiding the most pernicious aspects of their industrializing culture.

Like other antebellum reform movements, the diet reformers established an organization through which to spread their message. The American Physiological Society, founded in 1837 in Boston, aimed to convert Americans to diet reform. They believed their mission to be a dire one since they believed (as millennialists) that perfection of the individual was imperative before society could be perfected. The society sponsored lectures and publications and its members proselytized with the fervor of zealots. By June 1838, the APS claimed a membership of 251 men and women, all convinced of the rightness of plain living.

As with other reform movements, women played an important role in the APS in particular (making up a full quarter of its founding members) and the diet reform movement in general. Health reformers spelled out a specific place in their mission for women in their role as wives and mothers. And they offered a program that many middle-class women found attractive. It included urging male sexual restraint and rejecting medical practices that were particularly hard on women, especially those that pertained to pregnancy and childbirth.

While they gained adherents, Graham and his followers also attracted a good deal of ridicule and sometimes violent opposition. Since Graham’s system included a pointed an attack on the commercialization of food, it is not surprising that commercial food producers were among his most vociferous opponents. On more than one occasion, Boston butchers and bakers stormed Graham’s lectures. An irate mob in Portland, Maine, also prevented Graham from speaking about sexuality to mixed audiences. In response, Graham’s disciple Mary Gove Nichols began delivering lectures on diet reform to female audiences in Graham’s place.

Medical professionals, too, felt threatened by Graham’s unorthodox approach to attaining and preserving good health, as well as his direct condemnation of their profession. The pages of the Boston Medical and Surgical Journal (precursor to the New England Journal of Medicine) were filled with editorials, letters, and articles declaiming Graham and his theories. The popular press joined in, too. An 1836 article in the New York Review, for example, described Grahamism as "most pernicious and abhorrent, . . . a fanatical attempt to shut out from mankind certain sources of happiness and enjoyment, which were clearly provided and intended for them in the economy of the earth."[5]

The diet reformers did not have quite the impact that their opponents feared. In 1839 Graham retired, the American Physiological Society disbanded, and the Graham Journal of Health and Longevity published its final issue. But the reformers left their mark on popular ideas about diet and health. Domestic and personal advice manuals incorporated the tenets of health reform into their advice for proper living. For example, Catharine Beecher, perhaps the foremost advocate of education and domesticity in the nineteenth century, extolled the virtues of a vegetarian diet in her writings and urged parents not to feed their children overstimulating foods for fear of causing disease. So, too, cookbook writers incorporated Grahamism into their recipes and household advice, arguing that proper cookery was important since mothers could ruin their children’s characters by indulging the wrong appetites.

More formally, the diet reformers influenced subsequent health reforms like phrenology and the water cure (also known as hydropathy), which enjoyed significant popular appeal as alternative medical approaches in the mid-nineteenth century. Hydropathy itself spawned the most successful advocate of diet reform of the nineteenth century and one whose name many Americans see every morning on their breakfast table. In 1876, John Harvey Kellogg assumed the directorship of the hydropathic Western Health Reform Institute in Battle Creek, Michigan. In 1878, Kellogg began to market "granola," a Grahamite cereal, and other unrefined grain cereals. Kellogg thus established the foundation of the breakfast cereal industry, incorporating Grahamite principles into everyday American dietary practices.

The diet reformers continued to leave their mark on American history and American eating habits into the twentieth century. The organic movement of the 1960s recalled the diet reform movement of the previous century, again urging Americans to eschew overly processed foods and to shorten the distance between producer and consumer. These arguments have assumed more urgency and salience today as our food supply globalizes and many Americans become increasingly concerned about the quality, derivation, and processing of their food. Today’s food reform movements, including crusades for organic food and against obesity, have a very different shape and context from nineteenth-century diet reform. But some of their arguments are quite similar to those espoused by Graham and his followers.

As we face sometimes-unsettling facts about our contemporary food supply, it is constructive to recall an earlier era of diet reform. That period also involved significant change both to American society and culture and the food supply itself. The diet reformers firmly believed they had the tools to adjust to these changes. For them, the road to individual and societal salvation began in their stomachs.

[1] "Art. IV," New York Review 2 (October 1837), 336.

[2] Sylvester Graham, Lectures on the Science of Human Life (Boston: Marsh, Capen, Lyon, and Webb, 1839), 2:537.

[3] Quotation from Edith Walters Cole, "Sylvester Graham, Lecturer on the Science of Human Life: The Rhetoric of a Dietary Reformer" (PhD dissertation, Indiana University, 1975), 220.

[4] Frances Trollope, Domestic Manners of the Americans, ed. Donald Smalley (New York: Vintage Books, 1949), 18–19.

[5] "Art. IV," New York Review 2, 336.

Cindy Lobel is assistant professor of history at Lehman College, The City University of New York. Among her publications are "Out to Eat: The Emergence and Evolution of the Restaurant in Nineteenth-Century New York City," in Winterthur Portfolio (2010), "Women in Nineteenth-Century America," in Clio in the Classroom (2009), and the entry on "Pizza" in The Encyclopedia of New York State (2004). She is currently at work on The Appetite of the Metropolis: Food, Eating, and Culture in New York City, 1790–1890 and a biography of nineteenth-century writer and reformer Catharine Beecher for Westview Press’s American Women’s Lives Series, edited by Carol Berkin.