Memorializing the Gravesites of Twentieth-Century African Americans

by Karla F. C. Holloway

Excerpts reprinted by permission of Karla F. C. Holloway from her book Passed On: African American Mourning Stories (Duke University Press, 2003).

I wandered for an hour trying to find Harriet Tubman (1913). I didn’t mind the time. I had grown used to these searches, and I came to depend on their quiet and solitude, feeling comfort and ease in these stilled cemetery spaces. . . . Most of the time I traveled alone, but there were trips when my husband and daughter accompanied me. That time, my fourteen-year-old niece Aziza came along, persuaded to go on the two-hour drive from my parents’ home in Buffalo to the Auburn, New York, cemetery if I would agree to listen to her Prince tapes while we traveled. It was an easy bribe: I wanted her company and I like Prince.

When we entered the cemetery gates on that Sunday summer morning, there was only one person stirring who might have some indication of where we could find Harriet Tubman. He guided his lawnmower neatly and carefully between the tombstones as if there were years of practice and respect for the grounds governing his labor. It’s under that really big tree on the south side along the wall, he told us—not particularly happy, it seemed, with our distracting presence. So, we thanked him and walked there, following the wall’s back route, Aziza asking at each gravestone, Maybe that one? And me thinking how each grave was reminiscent of Dickinson’s “a swelling in the ground.” Suddenly, a massive cypress emerged from the leafy vista that had obscured it, and there was Harriet.

Some years into the process of writing [Passed On], I left behind the sense I was searching for tombstones. I was looking instead for Harriet, or Billie, or Richard. It became a personal, even an intimate, sojourn among my cultural kin. When we found Billie Holiday’s (1959) grave in New York City, the lyrics and melody of “God Bless the Child” moved from memory to mouth, and soon I was standing in full-voiced song before the tombstone she shared with her mother. An elderly White couple, tending a grave some rows down, left their work and came to where I stood with Billie and her mother and asked if I knew her. Before I could help it, I heard myself say, Oh yes, she’s my great aunt. Of course, it wasn’t at all true, but at that moment, I felt like kin. Well, we take care of her, they told me. Whenever we come to tend our parents’ graves, we clear away any weeds in front of Miss Holiday’s as well. I was touched by their neighborliness and told them so. I think I even said the family will be so grateful. I know I could have said this; it would have been easy. Poetic license.

Some years into the process of writing [Passed On], I left behind the sense I was searching for tombstones. I was looking instead for Harriet, or Billie, or Richard. It became a personal, even an intimate, sojourn among my cultural kin. When we found Billie Holiday’s (1959) grave in New York City, the lyrics and melody of “God Bless the Child” moved from memory to mouth, and soon I was standing in full-voiced song before the tombstone she shared with her mother. An elderly White couple, tending a grave some rows down, left their work and came to where I stood with Billie and her mother and asked if I knew her. Before I could help it, I heard myself say, Oh yes, she’s my great aunt. Of course, it wasn’t at all true, but at that moment, I felt like kin. Well, we take care of her, they told me. Whenever we come to tend our parents’ graves, we clear away any weeds in front of Miss Holiday’s as well. I was touched by their neighborliness and told them so. I think I even said the family will be so grateful. I know I could have said this; it would have been easy. Poetic license.

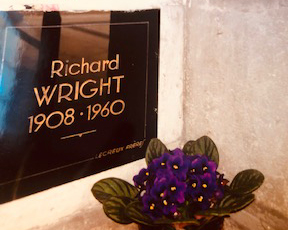

I left a flower at the gravesite of each twentieth-century African American I wanted to memorialize with this project. And, despite all the various shades that have dimmed the past years of my own life, I can remember distinctly each moment when I discovered a grave. The shivering embrace of the chilled air on one fall afternoon in Paris is with me still. At Le Cimetière du Père-Lachaise, I walked, without sense of or concern for the time that was passing, down byways thickened with monuments. I did not know then that there was a cemetery map that would have led me directly to the columbarium and Richard Wright’s (1960) space there among the cremated.

It was only after reading hundreds upon hundreds of names that I found his square of black granite that, nestled in the corner where I knelt to reach it, reflected my own tear-filled eyes back at me, either the wind or the memory rising to my gaze. Its gold lettering was simple and clear—starkly projected against the dark stone. My hand trembled as I placed a pot of African violets at the base of the wall. And, then, I waited there, until the sense that the moment had done what it would passed. Before I left, I tucked just a few of the African violet’s blossoms into the crack between the wall and Wright’s stone. Poor Richard, I mumbled, remembering an essay with that name. I laid the flat of my palm against the stone and held it there. How shall you be remembered? I traced the deep etching of the bright letters in his name.

It was only after reading hundreds upon hundreds of names that I found his square of black granite that, nestled in the corner where I knelt to reach it, reflected my own tear-filled eyes back at me, either the wind or the memory rising to my gaze. Its gold lettering was simple and clear—starkly projected against the dark stone. My hand trembled as I placed a pot of African violets at the base of the wall. And, then, I waited there, until the sense that the moment had done what it would passed. Before I left, I tucked just a few of the African violet’s blossoms into the crack between the wall and Wright’s stone. Poor Richard, I mumbled, remembering an essay with that name. I laid the flat of my palm against the stone and held it there. How shall you be remembered? I traced the deep etching of the bright letters in his name.

Later, I actually came to prefer to search without a map, to wander these serene spaces unguided, giving the imaginations I constructed about my grave meanderings time to develop. When the caretaker in Monaco told me that not one of Josephine Baker’s children came to visit their mother’s grave, my English “tsk tsk” echoed hers in French. Back in the United States, my husband Russell and I saw the tributes of coins on the gravestone of Louis Armstrong (1971). A submarine sandwich had been divided, its halves placed on each of the in-ground markers that lay before the tombstone (one marking the space for Louis, the other for his wife Lucille). There was a soda on hers and a can of Fosters on his, the condensation on his can still apparent. We took the photograph quickly, not wanting to intrude on that loving gesture (which Josephine should have had from someone who cared at least that much). As we left, I looked back through the quickly dissolving haze of the early morning. And, as I walked away, it seemed as if the white marble trumpet atop his memorial had no foundation, that it hovered over the site, like his music lingers in our national memories.

That visit’s haze and harmony was like another early morning visitation, this one as far south as the other had been north. In St. Louis Cemetery Number I, near Voudou priestess Marie Laveau and the Morial family vault is the vault of Homer Plessy, the litigant in the famous civil rights case Plessy v. Ferguson, which made legal the ethic, as well as the practice, of “separate but equal.” Perhaps it was the jumble of spiritual energies in New Orleans, and especially in the cemeteries, that interrupted any individual sense of Plessy. Instead, decades of jazz funerals and the tremendous crush of sight and sound, movement and melody saturated the thick New Orleans air. Later that day I wished that Mahalia Jackson could be there as well. As austere and stately as her gated marble edifice might be, at the edge of a cemetery just outside of New Orleans, there was no way to recall her spirit to the noisy space of her plot, which was too near the highway, power lines, and a culvert of dirty water. I wished instead she had been in the company of the surreal cities of the dead in downtown New Orleans.

I had no such regrets when I found Arthur Ashe (1993). I was grateful for the decision of his family to keep him and his mother, Mattie Ashe, in the historically Black cemetery Woodland. The family gated the small plot where tombstones of Arthur and Mattie now stand together. But the iron pickets that surround his and his mother’s gravestones did not imply separation from others in that Black cemetery in Richmond, although Arthur’s is certainly a memorial of greater size and note than the others in its company, including hers. Instead, it seemed to lovingly enclose him and his mother, and I felt there a spirit of embrace rather than separation. I found both Woodland and Arthur’s gravesite quite easily, as the caretaker I had called had assured me I would. He told me that I could not miss it on the left, as I drove up the short, winding road to the cemetery gates of that historical burying ground for Blacks in Richmond.

The historical practice of maintaining separate graveyards for Blacks and Whites in this country was one that continued, in fits and starts, throughout the twentieth century, although in the later years of that century, after bias became a federal wrong, that practice persisted more as a matter of choice for both races. . . . Outright bias, shameful conduct, and a generally quiet history of preference in the habits of many graveyards recalled the practices of the funeral homes and churches that brought them their dead.

Only three days had passed since Whitney Elaine Johnson, an infant, had been buried in Barnett Creek Baptist Church Cemetery in Thomasville, Georgia, when church deacons approached her obviously grief-stricken mother and asked that she exhume her daughter’s body and move her to a “cemetery that would accept blacks.” Although it was 1996, the Baptist fellowship at Barnett Creek was not quite ready to change a “lifetime” policy at their cemetery, which “had been segregated for as long as anyone can remember,” even for a biracial child whom they had not identified as Black until her father showed up to visit his daughter’s grave. Fortunately, before the baby was exhumed, these deacons reversed their decision, succumbing, albeit reluctantly, to the glaring light of a curious and challenging media onslaught. Although the story of the deacons’ request to preserve the all-White cemetery in Thomasville became public, there were many similar stories at the century’s end that were successfully and privately buried. Thomasville, Georgia’s, story just happened to be one that earned the attention of the press; others were able to quietly continue a history of separation under cover of the weight of tradition. Whitney’s grandmother bemoaned this state of affairs in her hometown, saying, “this isn’t the 1950’s.”[1]

She must have known that era well. At that time, even a veteran’s uniform could not break the code in some US cemeteries. In 1952, Greenwood Memorial Park in Phoenix refused to bury Pfc. Thomas Reed, a nineteen-year-old soldier killed in Korea. His body lay in a mortuary vault, and Lincoln Ragsdale Sr. defiantly left him there, unburied, for three months until the cemetery trustees voted to rescind their racist policies. In the same era, Black families in Michigan were also forced to contend with the issue of segregated cemeteries; according to a 1959 letter to Gordon Parks, for instance, Black families in Flint “buried their kin in Saginaw because only one undertaker and one burial ground in their hometown accepted blacks.”[2] It wasn’t until 1966, when the Michigan Court of Appeals upheld the case of J. Spencer, whose mother was denied burial in Flint’s Memorial Park because she was African American, that the county cemeteries dropped their bans against nonwhites.[3] If one were to track the history of such stories, one might expect that perhaps African American Korean War veterans would have been the last to experience blatant racism and lack of respect from their countrymen. But, even in the Vietnam era, Black veterans found a macabre kinship with their Korean War counterparts. In Ft. Pierce, Florida (Zora Neale Hurston’s final resting place), it took federal legislation to make room for a Black Vietnam veteran. Despite the fact that he had been “given military honors at an armory,” that veteran’s 1970 eulogy characterized him as a “man without a country.”[4]

Although cemetery desegregation was juridically assured in 1968, when the Supreme Court ruled in Jones v. Mayer using an 1866 civil rights law that guaranteed Blacks equal rights in making and enforcing contracts and purchasing personal property, local legislation was slow to acknowledge the impact of that ruling. The conduct of cemeteries toward African Americans often extended beyond belief and common sense. Not until midcentury did the national cemetery at Arlington begin accepting the bodies of loyal Black veterans for burial. It did not matter that, during the last years of the Civil War, the Freedmen’s Village of nearly 3,000 Black people existed on what were the eventual grounds of Arlington National Cemetery. Nor did it matter that 2,700 members of that Black population were already buried there. The United States maintained Arlington as a segregated national cemetery until 1948, well after the two world wars that filled both urban and rural cemetery plots with deceased Black veterans. Little wonder that the prominent African Americans who are buried in Arlington today attract such respectful attention and notice.

Thurgood Marshall’s (1993) grave stands there, an American flag visible in the distance and, ironically, the great columns of the Robert E. Lee house, on a hill in the background, look much like the ones on the Supreme Court building where Marshall labored over the constitutional consequences of the nation’s legal doctrine for thirty-three years. Many of the twentieth-century African Americans buried at Arlington had a critical impact in the construction of the nation’s cultural history. Joseph Louis Barrow’s (1981) gravesite is there as well, his classic pugilistic pose reaching out from one side of the granite marker, enacting the determination that characterized his life. Also in Arlington, just to the left of a massive sphere that identifies the man buried beneath as the “discoverer of the North Pole,” is a particular black granite tombstone shaped just like Arthur Ashe’s. Like Ashe’s, it is adorned with a bronze and gold relief and bears an engraving that effectively back-talks the site to its right. Matthew Henson’s (1955) tombstone guarantees that the story of his life, which did not gain respect and credibility while he lived, would be explicit after his death—it identifies him as the “co-discoverer” of the North Pole.

It was not always that explicit. I think that scientist George Washington Carver’s (1943) grave is sometimes overlooked, with his more famous colleague, Booker T. Washington, often gaining the greater notice. Carver’s gravesite at Tuskegee University was ringed with plastic flowers when I saw it. I wanted to remove them and leave something more dignified. The faded plastic blossoms seemed less than this great agricultural scientist deserved. But I found some measure of contentment sitting on the curved bench that was placed just at the foot of Carver’s aged concrete marker and that provided an appropriate place for pause and consideration of his accomplishments at Tuskegee.

It was not always that explicit. I think that scientist George Washington Carver’s (1943) grave is sometimes overlooked, with his more famous colleague, Booker T. Washington, often gaining the greater notice. Carver’s gravesite at Tuskegee University was ringed with plastic flowers when I saw it. I wanted to remove them and leave something more dignified. The faded plastic blossoms seemed less than this great agricultural scientist deserved. But I found some measure of contentment sitting on the curved bench that was placed just at the foot of Carver’s aged concrete marker and that provided an appropriate place for pause and consideration of his accomplishments at Tuskegee.

Not all gravestones properly indicate the era and moment of the deceased. Although the historic grounds of Oakwood Cemetery in Chicago seemed to promise an aged and period-appropriate stone for the gravesite of the anti-lynching crusader and feminist activist Ida B. Wells, nothing in the marker that lies across her grave indicates the era of her passing. Instead, she shares a fairly modern granite tombstone with her husband Ferdinand, a nod to a late-century decision to “improve” her gravesite. Oakwood’s current owners do not rest on the distinguished history of its residents; they are still in the business of drumming up patrons. When my husband and I went in search of Ida B., the woman in the cemetery office looked at us carefully, as if we were auditioning to get the information we wanted, which was simply the location of Symphony Shores, where Ida was buried. But she surprised us by asking if we were married. I said yes, wondering why that was in any way relevant. When she followed up by asking if we were interested in a plot for ourselves, I realized the business of burial never concludes.

Perhaps one of the most poignant postmortem stories of the twentieth century was told by Malcolm X’s (1965) modest gravesite in Ferncliff Cemetery—the story of a summer tragedy that echoed his own prophetic words: “It had always stayed in my mind that I would die a violent death. In fact, it runs in my family.” His gravesite had originally been marked with the small brass plate, riveted flat against the ground to a concrete slab, characteristic of all plots in the cemetery in Ardsley-on-Hudson. But, on a summer day thirty-one years after his death, I looked for Malcolm, only to find that the site had been disturbed and his marker removed, temporarily replaced with a bouquet of flowers that withered in the summer’s sun and a T-shirt with Malcolm’s words emblazoned in red across black cloth. At first I was merely disappointed, but then I realized why his marker was gone, and the tragic generational vitality of his own prophecy brought me to tears. His marker had been taken away so that his wife’s name, Betty Shabazz, could be engraved next to his. This was the summer of her death, which she had suffered in the hands of her grandson, Malcolm. Her body, but not her name, had already been placed next to his in the grassy, bronzed pathways of Ferncliff.

The stories of graveyards do not only point inward, toward the personal, but outward as well, to the public. Certainly, the dramatic difference between the final resting places of two men of the century’s most significant stature and renown—Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr. (1968)—suggests a very interesting postmortem narrative. I did not look very long before finding a parking place near the city block in Atlanta, Georgia, that had become King’s gravesite, mausoleum, museum, historical center, and souvenir site. It was early on a Sunday morning, and the city streets were not very busy. On the one hand, the megablock of King’s memorial symbolized the constantly evolving postmortem capitalist construction of his unique legacy, an ever-expanding legacy that does continue to benefit African Americans. But, when that site is juxtaposed with the modest gravesite of Malcolm, who is buried in a community of gone-but-not-forgotten souls, the narrative of culture, capital, and memory is apparent. I felt as if I had made a requisite tourist stop as I stood staring at King’s sarcophagus centered in the middle of a reflecting pool—but that was all I felt.

Although the century’s years and its passing customs can only occasionally be discerned in the gravesites of African Americans, there were still, at the end of the twentieth century, some southern Black burial grounds where one could find plots decorated with the remnants of broken dishes, glassware, bedframes, and shells—echoes of early traditions in West Africa and the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century enslaved Africans in America. The families of the deceased had nurtured a belief in the spiritual lives of their loved ones and, through the use of such decorative graveyard arts, broke the connection between the two worlds, eased the soul’s transition from one world to the next, and gave the traveling soul a place to rest. Even though the sculptural art of William Edmondson—whose grave markers were important additions to the gravesites of the “impoverished yet art-loving members of Nashville’s 1930s black community”—shifted from cemetery to museum once he was “discovered” by a Harper’s Bazaar photographer, the “urge to adorn,” as Zora Neale Hurston put it, followed the African American cultural spirit and did not end with the funeral.[5]

Those who gave shape and contour to African America in the twentieth century are not all here, within [this essay], nor are they fully memorialized in the photographs I have taken of their gravesites. But those who are here, chosen from each of the century’s decades, might appropriately stand in for the others.

Karla F. C. Holloway is James B. Duke Distinguished Professor Emerita of English at Duke University. She is the author of eight books, including Passed On: African American Mourning Stories (Duke University Press, 2003); Private Bodies/Public Texts: Race, Gender, and a Cultural Bioethics (Duke University Press, 2011); and Legal Fictions: Constituting Race, Composing Literatures (Duke University Press, 2014). Her recent publications include two novels, A Death in Harlem (TriQuarterly, 2019) and Gone Missing in Harlem (TriQuarterly, 2021).

[1] Rick Bragg, “Just a Grave for a Baby, but Anguish for a Town,” New York Times, March 31, 1996.

[2] Angelika Kruger-Kahoula, “On the Wrong Side of the Fence: Racial Segregation in American Cemeteries,” History and Memory in African-American Culture, ed. Genevieve Fabre and Robert O’Meally (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994, 130–49), 131.

[3] Angelika Kruger-Kahoula, “On the Wrong Side of the Fence: Racial Segregation in American Cemeteries,” 131–32.

[4] Angelika Kruger-Kahoula, “On the Wrong Side of the Fence: Racial Segregation in American Cemeteries,” 132.

[5] Richard J. Powell, Black Art and Culture in the Twentieth Century (London: Thames and Hudson, 1997), 84.