Lincoln and Whitman

by David S. Reynolds

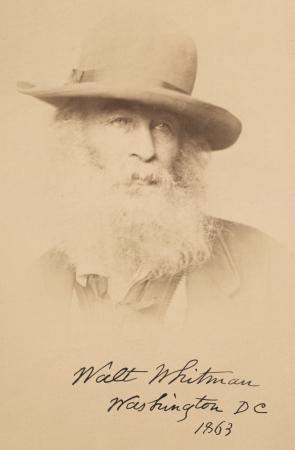

The relationship between Walt Whitman and Abraham Lincoln has long been the stuff of legend. According to one report, in 1857 Lincoln in his Springfield law office picked up a copy of Whitman’s poetry volume Leaves of Grass, began reading it silently, and was so entranced after half an hour that he started over, reading it aloud to his colleagues. Another anecdote, originally contained in an 1865 letter by a Lincoln aide, had Lincoln gazing out a White House window, spotting the hale, bearded Whitman walking by, and exclaiming, "Well, he looks like a man."

The relationship between Walt Whitman and Abraham Lincoln has long been the stuff of legend. According to one report, in 1857 Lincoln in his Springfield law office picked up a copy of Whitman’s poetry volume Leaves of Grass, began reading it silently, and was so entranced after half an hour that he started over, reading it aloud to his colleagues. Another anecdote, originally contained in an 1865 letter by a Lincoln aide, had Lincoln gazing out a White House window, spotting the hale, bearded Whitman walking by, and exclaiming, "Well, he looks like a man."

Although these stories may be apocryphal, they point to a kinship of spirits that was very real, if we judge from Whitman’s reaction to Lincoln. In Lincoln’s life, Whitman saw the comprehensive, all-directing soul he had long been seeking. In Lincoln’s death, he saw a grand tragedy that promised ultimate purgation and unification for America.

Whitman imagined Lincoln long before he saw him in person. In his 1856 political tract The Eighteenth Presidency! Whitman expressed disgust with the rampantly corrupt American political landscape and called for a "Redeemer President of These States," who would come out of "the real West, the log hut, the clearing, the woods, the prairie, the hillside." Whitman said he would be:

much pleased to see some heroic, shrewd, fully-formed, healthy-bodied, middle-aged, beard-faced American blacksmith or boatman come down from the West across the Alleghenies, and walk into the Presidency, dressed in a clean suit of working attire, and with the tan all over his face, breast, and arms.

When Lincoln arrived on the national scene six years later, he was all Whitman could have hoped for. On February 19, 1861, Whitman was among a throng of curious spectators in New York City who saw the president-elect arriving at the Astor House Hotel during his stopover in the city on his trip from Springfield to Washington, DC. During the war, when Whitman was a government worker and volunteer hospital nurse in Washington, he saw Lincoln some twenty to thirty times. He didn’t meet the President, but spotted him riding through the city for business or pleasure. "I see the President almost every day," he wrote in the summer of 1863. "We have got so that we exchange bows, and very cordial ones." Once Lincoln gave Whitman a long friendly stare. "He has a face like a Hoosier Michel Angelo," Whitman wrote, "so awful ugly it becomes beautiful, with its strange mouth, its deep cut, criss-cross lines, and its doughnut complexion."

No other human being seemed as multifaceted to Whitman as Lincoln. The President, he said, had "canny shrewdness" and "horse-sense." He seemed the down-home, average American, with his drab looks and his humor, redolent of barnyards and barrooms. Whitman commented on the "somewhat rusty and dusty appearance" of Lincoln, who "looks about as ordinary in attire, etc. as the commonest man." Whitman was excited that "the commonest average of life—a railsplitter and a flat-boatsman!"—now occupied the presidency.

Funny and unaffected, Lincoln nonetheless appeared basically sad; there was, Whitman wrote, "a deep latent sadness in the expression." He was "very easy, flexible, tolerant, almost slouch, respecting the minor matters," but capable of "indomitable firmness (even obstinacy) on rare occasions, involving great points." He was a family man but had an air of complete independence: "He went his own lonely road," Whitman said, "disregarding all the usual ways—refusing the guides, accepting no warnings—just keeping his appointment with himself every time." His "composure was marvellous" in the face of unpopularity and great difficulties during the war. He had what Whitman saw as a profoundly religious quality. His "mystical foundations" were "mystical, abstract, moral and spiritual," and his "religious nature" was "of the amplest, deepest-rooted, loftiest kind." Summing Lincoln up, Whitman called him "the greatest, best, most characteristic, artistic, moral personality" in American life.

Whitman admired Lincoln from the beginning, and his admiration increased over time. Just as Lincoln said early on that he was pursuing the war to preserve the Union rather than to extirpate slavery, so Whitman was devoted to the idea of Union. Like Lincoln, Whitman had long mistrusted both abolitionists and fire-eaters because they were disunionists who called for the separation of the North and the South. The poet was delighted when the war brought things to a head. "By that war," he said, "exit fire-Eaters, exit Abolitionists." The South’s greatest sin, he thought, was secession; the North’s greatest virtue was devotion to the Union. Lincoln, weaned on the Henry Clay school of nationality, epitomized this virtue above all. Whitman declared of Lincoln that "UNIONISM, in its truest and amplest sense, formed the hardpan of his character."

In short, Lincoln, as Whitman saw him, was virtually the living embodiment of the "I" of Leaves of Grass. He was "one of the roughs," but also, for Whitman, "a kosmos," with the whole range of qualities that term implied. If, as Whitman said, Leaves of Grass and the war were one, they particularly came together in Lincoln.

As impressive as Lincoln was in life, it was his death that for Whitman was the crucial, transcendent moment in American history. John Wilkes Booth’s murder of Lincoln in Washington’s Ford Theatre on April 14, 1865—witnessed firsthand by Whitman’s close friend Peter Doyle—had, in the poet’s view, an unequalled impact on the Republic. Whitman became fixated on what he called "the tragic splendor of [Lincoln’s] death, purging, illuminating all."

For him, Lincoln’s death offered a model for social unification. In it, he declared, "there is a cement to the whole people, subtler, more underlying, than any thing written in constitution, or courts or armies." The reminiscence of Lincoln’s death, he noted, "belongs to these States in their entirety—not the North only, but the South—perhaps belongs most tenderly and devotedly to the South." Lincoln had been born in the South—Whitman called him "a Southern contribution"—and he had shown kindness to the South during the war. Several of his generals, including Sherman and Grant, had connections to the South. In death, Lincoln became the Martyr Chief, admired by many of his former foes.

In life and death, Lincoln had, in Whitman’s view, accomplished the cleansing and unifying mission that Whitman himself had designed for Leaves of Grass. It is not surprising that Whitman’s writing changed dramatically after the Civil War. Never again would he write all-encompassing poems like "Song of Myself" or "The Sleepers." Although fresh social problems after the war would impel Whitman to insist on the poet’s vital social role, never again would he produce poems reflecting this mission in a large-scale way. His poetic output decreased, and he left it to other "bards" to resolve the social ills he saw.

In Whitman’s best-known poems about Lincoln, "O Captain! My Captain!" and "When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d," the silencing of his former poetic self is noticeable. Both poems marginalize Whitman and concentrate on Lincoln, presaging the poet’s obsession with Lincoln in late years. In "O Captain!" the fixation is visible in the image of the "I" staring relentlessly at Lincoln’s bloody, pale corpse on the ship of state’s deck amid celebrations heralding the ship’s return to port. In "Lilacs," Lincoln is the majestic western star, while the poet is the wood thrush, the "shy and hidden bird" singing of death with a "bleeding throat." No longer does Whitman’s brash "I" present himself as the Answerer or arouse readers with a "barbaric yawp." In the war and Lincoln, many of the nation’s most pressing problems had reached painful resolution, changing the poet’s role from that of America’s imaginary leader to that of eulogist of its actual leader.

In "Lilacs," self-assertive individuality is replaced by self-effacing grief. The poem has an abstract, generalizing quality; even Lincoln is not named or described. The death of hundreds of thousands of Americans in the war and the murder of the nation’s leader impel Whitman to contemplate death generally. There is a simplicity and transparency about the poem’s three symbols: the star (Lincoln), the bird (the poet), and the sprig of lilac (his poem of eulogy). The war and its tragic climax have brought things into focus. "I understand you," he writes of the thrush, and of the western star: "Now I know what you must have meant a month since as I walk’d." Death has become, in the words of the thrush’s song, a "strong deliveress" to be glorified above all. The deaths of the soldiers and Lincoln are to remain personal and cultural reference points, as perennial as nature’s rhythms. Whitman ends by reaffirming Lincoln’s centrality and by bringing together the three symbols in a proclamation of unity:

For the sweetest, wisest soul of all my days and lands—and this

for his dear sake,

Lilac and star and bird twined with the chant of my soul,

There in the fragrant pines and the cedars dusk and dim.

During the two decades after the war Whitman delivered a speech on "The Death of Abraham Lincoln" over and over again. "O Captain! My Captain!" became his most popular poem, endlessly reprinted and anthologized. The poem, with its regular meter and melodramatic imagery, became a source of embarrassment for the poet, who confessed to his friend Horace Traubel: "I’m honest when I say, damn My Captain and all the My Captains in the book!" Still, he recited the poem publicly time and again, and his devotion to Lincoln was unwavering. In 1890, two years before his death, Whitman declared, "I hope to be identified with the man Lincoln, with his crowded, eventful years—with America as shadowed forth into those abysms of circumstances. It is a great welling up of my emotion sense: I am commanded by it."

By that time, Whitman was widely identified with Lincoln. Well into the twentieth century, thousands of American schoolchildren were required to memorize "O Captain! My Captain!" Even today, the Rail-Splitter and the Good Gray Poet linger in the American memory as intertwined pioneers of American democracy.

David S. Reynolds, Distinguished Professor of English at The Graduate Center, The City University of New York, and a Bancroft Prize winner, is the author of John Brown, Abolitionist: The Man Who Killed Slavery, Sparked the Civil War, and Seeded Civil Rights (2005); Walt Whitman’s America: A Cultural Biography (1996); and Beneath the American Renaissance: The Subversive Imagination in the Age of Emerson and Melville (1989).