Her Hat Was in the Ring: How Thousands of Women Were Elected to Political Office before 1920

by Wendy E. Chmielewski

In 1866, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, the well-known leader of the woman’s rights movement, declared her intention to run for Congress, from Brooklyn, New York. Stanton was probably the first woman to campaign for a federal office. It would be another fifty years before the first woman took her seat in Congress. In 1916, Jeannette Rankin, a Republican from Montana, was elected and served in the US House of Representatives from 1917 to 1919. Far less well known is the fact that in the decade before Stanton announced her intention to campaign for office, four women had been elected to local and county offices in three states. In 1853 Olive Rose was elected county recorder by the voters of Lincoln County, Maine; the following year Adeline T. Swift of Penfield, Ohio, was elected to the Board of Supervisors; and the next year, 1855, Marietta Patrick and Lydia Hall were elected to the school board of Ashfield, Massachusetts. Voters in Maine, Ohio, and Massachusetts were all male in the 1850s. In the decade following Stanton’s campaign, more than sixty women were elected to local political offices. But these early women politicians were only the first of the 5,000–6,000 women who gained elected office across the United States between 1850 and 1920. The woman suffrage movement has been considered the primary civil rights movement for women, but the right to be elected to political office has its own history and is also an important marker of women’s fight for full citizenship.

In 1866, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, the well-known leader of the woman’s rights movement, declared her intention to run for Congress, from Brooklyn, New York. Stanton was probably the first woman to campaign for a federal office. It would be another fifty years before the first woman took her seat in Congress. In 1916, Jeannette Rankin, a Republican from Montana, was elected and served in the US House of Representatives from 1917 to 1919. Far less well known is the fact that in the decade before Stanton announced her intention to campaign for office, four women had been elected to local and county offices in three states. In 1853 Olive Rose was elected county recorder by the voters of Lincoln County, Maine; the following year Adeline T. Swift of Penfield, Ohio, was elected to the Board of Supervisors; and the next year, 1855, Marietta Patrick and Lydia Hall were elected to the school board of Ashfield, Massachusetts. Voters in Maine, Ohio, and Massachusetts were all male in the 1850s. In the decade following Stanton’s campaign, more than sixty women were elected to local political offices. But these early women politicians were only the first of the 5,000–6,000 women who gained elected office across the United States between 1850 and 1920. The woman suffrage movement has been considered the primary civil rights movement for women, but the right to be elected to political office has its own history and is also an important marker of women’s fight for full citizenship.

In most states, to be eligible for elected office a citizen had to be a voter. In most locales this excluded women from office. However, challenges to the unequal citizenship status of women began in the first years of the early Republic. From the mid-1790s until 1807 property-owning women in New Jersey could vote alongside their male counterparts.[1] Changes to women’s voting rights began in the 1850s and 1860s with women in Michigan (1855) and women in Kansas (1861) gaining the right to vote for school board members and educational officers. Women in Wyoming gained full suffrage in 1869. By the end of the century women in twenty-six states across the country had gained school suffrage, allowing them to vote for members of school boards and superintendents of schools. In some states women also gained municipal suffrage making them eligible for local or state offices as well. These were all hard-fought battles to prove that women could be voters and participate in politics if only on the local and state levels. When the Nineteenth Amendment was ratified in August 1920, women in sixteen states already had full suffrage rights, and women had been elected to political office in forty-three states.

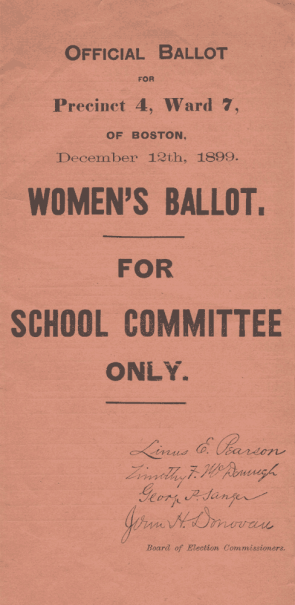

In most states, to be eligible for elected office a citizen had to be a voter. In most locales this excluded women from office. However, challenges to the unequal citizenship status of women began in the first years of the early Republic. From the mid-1790s until 1807 property-owning women in New Jersey could vote alongside their male counterparts.[1] Changes to women’s voting rights began in the 1850s and 1860s with women in Michigan (1855) and women in Kansas (1861) gaining the right to vote for school board members and educational officers. Women in Wyoming gained full suffrage in 1869. By the end of the century women in twenty-six states across the country had gained school suffrage, allowing them to vote for members of school boards and superintendents of schools. In some states women also gained municipal suffrage making them eligible for local or state offices as well. These were all hard-fought battles to prove that women could be voters and participate in politics if only on the local and state levels. When the Nineteenth Amendment was ratified in August 1920, women in sixteen states already had full suffrage rights, and women had been elected to political office in forty-three states.

A piecemeal set of suffrage and electoral rights across the states and territories did not stop some women from campaigning for political office in their towns, counties, and states. Between 1853 and 1920 close to 6,000 women ran in more than 7,500 political campaigns, and many were elected. In forty-three states and territories, single and married women, representing nineteen political parties, had campaigned for sixty different offices. The histories of these women have been mostly forgotten, apart from a few famous women, such as Stanton. The "Her Hat Was in the Ring" digital history project seeks to bring the stories of these women to light.[2] This online project currently contains information on more than 3,500 women who campaigned for political office.[3] Searches by state, political party, and political office may also be performed.

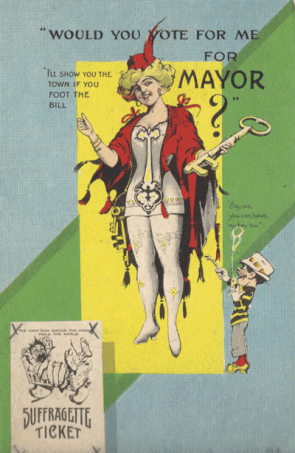

Who were these women elected to local offices including mayor, town council member, county treasurer and recorder of deeds, and justice of the peace? About fifty percent of women ran for educational offices (school board members, county and state superintendents of schools, and university trustees), mostly because those were the first offices open to women. The incumbents were significant political players in their communities, deciding on the disposition of school tax monies, influencing the local direction of education and school land purchases, and determining access to higher education. The offices carried community status and influence and paid a reasonable salary, allowing many women to support themselves and their families. Campaigns for these offices were frequently highly contested races by men and women. When deciding to compete, the women ran full campaigns, provided interviews for newspapers, distributed campaign literature, had campaign songs, made stump speeches, and attended party conventions. In some states, without traditional support of local party machines, female candidates relied on the support of women’s organizations often involved in reform movements—women’s rights, health reform, temperance, child welfare, and labor rights. In the 1896 campaign in Illinois, candidate Lucy Flowers used the opportunity to create coalitions with emerging race-based political organizations.

Who were these women elected to local offices including mayor, town council member, county treasurer and recorder of deeds, and justice of the peace? About fifty percent of women ran for educational offices (school board members, county and state superintendents of schools, and university trustees), mostly because those were the first offices open to women. The incumbents were significant political players in their communities, deciding on the disposition of school tax monies, influencing the local direction of education and school land purchases, and determining access to higher education. The offices carried community status and influence and paid a reasonable salary, allowing many women to support themselves and their families. Campaigns for these offices were frequently highly contested races by men and women. When deciding to compete, the women ran full campaigns, provided interviews for newspapers, distributed campaign literature, had campaign songs, made stump speeches, and attended party conventions. In some states, without traditional support of local party machines, female candidates relied on the support of women’s organizations often involved in reform movements—women’s rights, health reform, temperance, child welfare, and labor rights. In the 1896 campaign in Illinois, candidate Lucy Flowers used the opportunity to create coalitions with emerging race-based political organizations.

The data show that in the earlier candidacies women campaigned to win; examples include the 1869 campaign of Iowan Julia Addington for county superintendent of schools, and the women of the Boston School Committee (1873–1874). In contrast, the early candidacies of women who ran for federal office—Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and presidential candidates Victoria Woodhull (1872) and Belva Lockwood (1884 and 1888)—were symbolic efforts initiated as part of the woman’s rights movement. Women ran on major and third-party tickets including the Prohibition Party and various socialist parties. The midwestern states ran or elected the largest numbers of women, followed by western states. Women in the Northeast were successful in election to local school boards. In general, women were surprisingly successful in campaigns on the local level for such offices as mayor, city council, and town clerk, and for state representative. By the turn of the century, Republicans had the most female candidates, with Democrats a close second.[4] Major party female candidates were more successful than their third-party counterparts.

The data show that in the earlier candidacies women campaigned to win; examples include the 1869 campaign of Iowan Julia Addington for county superintendent of schools, and the women of the Boston School Committee (1873–1874). In contrast, the early candidacies of women who ran for federal office—Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and presidential candidates Victoria Woodhull (1872) and Belva Lockwood (1884 and 1888)—were symbolic efforts initiated as part of the woman’s rights movement. Women ran on major and third-party tickets including the Prohibition Party and various socialist parties. The midwestern states ran or elected the largest numbers of women, followed by western states. Women in the Northeast were successful in election to local school boards. In general, women were surprisingly successful in campaigns on the local level for such offices as mayor, city council, and town clerk, and for state representative. By the turn of the century, Republicans had the most female candidates, with Democrats a close second.[4] Major party female candidates were more successful than their third-party counterparts.

Women of a broader than expected range of geographical, ethnic, and status backgrounds campaigned for office. Amanda T. Million of Kentucky was the first woman in the South elected to public office (county superintendent of instruction, 1886), but southern states had the lowest number of female candidates in the nation. Anna R. Woodbey of Nebraska, president of her local Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, was perhaps the first African American woman nominated for political office (Prohibition Party, 1895). Pauline Steinem, grandmother of modern feminist activist Gloria Steinem, may have been the first Jewish woman elected to office. She was a coalition candidate elected to the Toledo city school board in 1904. Women of ethnic backgrounds beyond the mainstream had a mixed rate of participation in the electoral process, and this depended on period, region, or locale. For example, in the West and Midwest women of Irish heritage were often candidates with no comment made

Women of a broader than expected range of geographical, ethnic, and status backgrounds campaigned for office. Amanda T. Million of Kentucky was the first woman in the South elected to public office (county superintendent of instruction, 1886), but southern states had the lowest number of female candidates in the nation. Anna R. Woodbey of Nebraska, president of her local Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, was perhaps the first African American woman nominated for political office (Prohibition Party, 1895). Pauline Steinem, grandmother of modern feminist activist Gloria Steinem, may have been the first Jewish woman elected to office. She was a coalition candidate elected to the Toledo city school board in 1904. Women of ethnic backgrounds beyond the mainstream had a mixed rate of participation in the electoral process, and this depended on period, region, or locale. For example, in the West and Midwest women of Irish heritage were often candidates with no comment made  on their background or ancestry, but in Boston, the rise of Irish women candidates for the school board was a watershed event in the city.

on their background or ancestry, but in Boston, the rise of Irish women candidates for the school board was a watershed event in the city.

Throughout the second half of the nineteenth century and into the first decades of the twentieth century, these brave women challenged laws and social norms that often denied them access to political office. Women elected to office provided political leadership, had the opportunity to write laws for their communities, created and directed educational policies, spent community monies and taxes, created or denied opportunities for their fellow citizens, and legally represented their communities in legislatures, courts, and local forums. On a personal level they enjoyed prestige, a steady salary, and the opportunity to create change. These were women chosen by their fellow citizens, voting women and men, to represent their communities in the halls of government. At a time when many still believed that women should not even vote for those representatives, never mind write laws and lead government themselves, these women led the way into the future. Discovering this history reminds us that Americans have long challenged and redefined the parameters of citizenship—fighting, changing, and finding ways to include more people in the community of democracy.

[1] In an article entitled "Female Suffrage in New Jersey," the anti-slavery newspaper, The Liberator, reported that African American women voted in Hunterdon County, New Jersey in 1802, "and their ballots elected a member of the Legislature" (The Liberator, Boston, November 20, 1857, p. 188).There was no specific source for this information included in the newspaper article. In 1807 the New Jersey legislature changed the law making only white men eligible to vote in the state.

[2] The "Her Hat Was in the Ring" project was founded in 2008 by Wendy E. Chmielewski (Swarthmore College Peace Collection), Jill Norgren (Emerita, John Jay College and CUNY Graduate Center), and Kristen Gwinn-Becker (independent scholar, founder and CEO of HistoryIT). The project web site is backed by a custom database, designed by the staff of HistoryIT.

[3] For a woman to be included in the "Her Hat Was in the Ring" project, she had to be nominated or declare her intention to run for elected office. Women who volunteered for community efforts, were hired for a public office, or were appointed to an office by an official or board of officials were not included in the project. Hundreds of thousands of American women volunteered to run their local public libraries, healthcare facilities, and civic associations; raised money for religious groups or for secular, social, and cultural institutions; and inspected community hospitals, orphanages, factories, and other institutions. Tens of thousands of women were hired for civil service or public offices, such as secretaries in legislatures, or on government boards, as post mistresses, etc. Tracking all the contributions of women to their communities in the second half of the nineteenth century and early twentieth century was beyond the scope of this research project. Additionally, we decided that asking fellow citizens for their vote and representing their communities as elected officials was a significant and unique marker of citizenship.

[4] Party affiliation is available for only about 50 percent of the women in the database. The data on Republican and Democratic Party affiliation is based on these figures. Just over half of all the women campaigners in this period ran for educational offices. In some states educational offices were non-partisan, while in others these offices were linked to a political party.

Wendy Chmielewski is the George Cooley Curator of the Swarthmore College Peace Collection. The recipient of a 2013 Gilder Lehrman Fellowship, she is the co-editor of Jane Addams and the Practice of Democracy and Women in Spiritual and Communitarian Societies in the United States.