Hanging by a Chad—or Not: The 2000 Presidential Election

by James Gormly

When Vice President Albert Gore Jr. and George W. Bush, governor of Texas, squared off in the 2000 presidential election, people predicted it was going to be a historic election. The November results would determine not only which party occupied the White House, but might also shift control of the Senate and the House of Representatives. Heightening the election drama, nearly every poll showed that the two presidential candidates were running head-to-head and that support from party regulars was equally solid on both sides. The election appeared to pivot on voters not closely affiliated with either party, especially in fifteen swing states. Further complicating the election were the two third-party candidates. Ralph Nader, Green Party, was expected to attract Gore supporters while Patrick Buchanan, Reform Party, could pull votes away from Bush.

When Vice President Albert Gore Jr. and George W. Bush, governor of Texas, squared off in the 2000 presidential election, people predicted it was going to be a historic election. The November results would determine not only which party occupied the White House, but might also shift control of the Senate and the House of Representatives. Heightening the election drama, nearly every poll showed that the two presidential candidates were running head-to-head and that support from party regulars was equally solid on both sides. The election appeared to pivot on voters not closely affiliated with either party, especially in fifteen swing states. Further complicating the election were the two third-party candidates. Ralph Nader, Green Party, was expected to attract Gore supporters while Patrick Buchanan, Reform Party, could pull votes away from Bush.

Despite the amount of time and money expended on the election and the potential for sweeping the political table, the campaign appeared lifeless with little heated debate and a lot of well-worn political rhetoric. Gore stressed the growing economy and the benefits of government programs. Bush called the incumbent Democrats taxers and spenders and, pointing to President Clinton’s scandals, stressed he would restore morality and dignity to the White House. Given their carefully scripted and nuanced positions on most of the issues, neither Gore nor Bush enjoyed a boost from the three presidential debates. Bush was strongest in rural areas and in the South, Midwest, and Mountain states. Gore’s support came largely from urban areas, minorities, and the Northeast and Pacific states. Many predicted Bush would win the popular vote while Gore would earn the necessary 270 votes in the Electoral College. Most political pundits thought the election hinged on three critical swing states: Pennsylvania, Michigan, and Florida. On the eve of the election, Time unveiled its poll showing Bush with 49 percent, Gore with 43 percent, Nader with 3 percent, and Buchanan with 1 percent of the vote. Newsweek’s special election edition’s cover simply said: "Cliffhanger."[1]

On Election Day, Tuesday, November 7, shortly after 7:00 p.m. Eastern Standard Time, working from exit polls, television commentators and news services began to announce their projected results. Gore was the projected winner in the northeastern states, including the swing state Pennsylvania. Below the Mason-Dixon Line, Bush racked up projected victories. Then, shortly before 8:00 p.m., the Associated Press and several television networks placed Florida and its twenty-five electoral votes in Gore’s column. Two hours later, they projected that Gore would be the forty-third president of the United States. CBS’s news anchor Dan Rather pronounced: "If we call a state, you can take it to the bank."[2]

In Austin, Bush, upon hearing from observers in Florida that the vote was too close to call, announced that he would wait until all the votes were counted. His assessment was correct as, minutes before 10:00 p.m., the networks and news services began backtracking. Dan Rather sheepishly admitted that Florida seemed to be going for Bush. As most midwestern and Rocky Mountain states were added to Bush’s totals, shortly after 2:00 a.m. the networks projected that Bush would carry Florida and become the next president. Believing it was over, Gore phoned Bush to congratulate him on his victory and left for the Nashville War Memorial Plaza to publicly concede the election. But, just as he arrived, he was told that Bush’s majority in Florida was less than 6,000 votes and that thousands of votes were still to be counted. Florida was again too close to call. Gore phoned Bush again at 3:30 and "un-conceded." At 4:00 a.m., the networks again reversed themselves and announced that Florida and the presidential election remained undecided. NBC anchor Tom Brokaw admitted the networks had erred again: "We don’t just have egg on our face – we have an omelet all over our suit."[3]

The nation awoke Wednesday to learn it would have to wait for an official recount in Florida, where Bush led Gore by 1,784 votes. New Mexico and Oregon were also recounting ballots, but their electoral votes (five and seven) were inconsequential compared to Florida’s. It was not the first time that a presidential election did not immediately crown a winner, but it had not happened since 1876—and Florida had been part of that dispute too. Few thought the recounting process would take long. State law said that recounts needed to be completed within seven days (by November 14) and be reported to Florida’s Secretary of State Katherine Harris by 5:00 p.m. that day. She would then certify those votes, but final certification of the winner would come only after all the absentee ballots were counted on November 17.

The machine recount was quickly completed. Bush remained the leader, although his lead was only 229 votes. The following day, Thursday, November 9, Secretary Harris prepared to certify the count and announce the results, but challenges to the totals from four counties—Broward, Miami-Dade, Palm Beach, and Volusia—halted the process. Florida’s election codes allowed for challenges by a candidate or voter. If the local court approved, the county canvassing board would conduct a partial manual count and if it found a problem that might change the results, it had to correct the problem. Conducting a complete hand count of all ballots was one option to fix the error.

All four counties wanted hand counts, but the Volusia canvassing board, which had already begun its manual count, recognized that it could not finish by the November 14 deadline. It asked the Florida circuit court to extend the deadline to allow all votes to be hand counted. The following day, the Democratic Party in Palm Beach filed suit to contest the vote count due to mistakes using the "butterfly" ballot. They argued that the structure of the butterfly ballot had caused many voters to mistakenly punch out the hole for Buchanan when they meant to vote for Gore. These, plus the ballots not read by the machines because the holes were not completely punched out, they claimed, created a significant "under vote." They pointed to thousands of ballots having two holes punched out (often for Buchanan and Gore) and many more with holes only partially punched, held on by one corner—quickly labeled the "hanging chad." They wanted those doing the manual recount to examine each ballot to determine the intention of the voter and to count the hanging chads. Later they successfully argued that other chads, including those only showing signs of being pushed—the "dimpled" and "pregnant" chads—also should be counted. Florida’s votes now appeared to depend on manual recounts and the nature of the chads. Counting chads was complicated and controversial, but it was nothing compared to the legal battles about to break.

Fearing the recounts might jeopardize Bush’s victory, his supporters sought to stop them through the courts. Although a US district court declined involvement, their hopes soared when Secretary of State Harris announced that in keeping with Florida law she would "ignore" all votes submitted after 5:00 p.m., November 14. Realizing that the vast majority of the votes being recounted would not be considered, Gore supporters asked the Florida Supreme Court to extend the deadline and require that the complete recounts be certified. The court agreed to hear the case, but did not issue a decision before the deadline, which allowed Harris to certify only those votes arriving before 5:00. Bush then led by 300 votes and unless the absentee ballot count or the Florida Supreme Court’s decision favored Gore, Bush would be certified the winner on November 17. The validity of absentee and mail-in ballots immediately became another set of lawsuits, but it was the Florida Supreme Court’s decision on November 16 that grabbed the headlines. The court halted Harris’ certification and announced a new deadline of 5:30 p.m., November 25. It also agreed to consider whether the secretary of state could ignore the additional recounted votes. Bush supporters protested; the National Review thought the decision scandalous and asked "if the courts pick the president what remains" of self-government.[4]

In presenting their views to the Florida justices, Bush’s lawyers stated that Florida’s law regarding recounts applied only when the errors were made in "voter tabulation" and not when the ballots were improperly marked by the voters. They also stated that the court could not change the law and force the secretary of state to accept the "late" recounted ballots, especially if those votes affected the electors, whose election is defined in Section II of the US Constitution. Gore’s lawyers stressed that the intention of the election law was to count as many ballots as possible, including those ballots rejected by the voting machines. It was illogical, they held, to go through the time-consuming hand count if those votes were not to be counted. The Florida Supreme Court, on November 21, agreed with Gore and declared that Harris had abused her position by ignoring recounted votes and reaffirmed their November 25 deadline. The decision precipitated two races: to complete the manual recounts and to either obtain or prevent the US Supreme Court’s intervention.

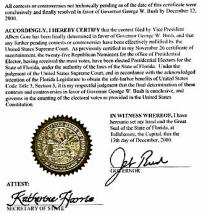

On Friday, November 25, those races appeared over. The recounts were still incomplete and those votes tabulated were not enough to give Gore a victory. In addition, the US Supreme Court had agreed to review the Florida court’s decision. At 7:30 p.m., Secretary Harris announced she was not including the recounted votes and that George W. Bush led by 537 and would receive Florida’s electoral votes. Bush declared victory. Gore, however, was unwilling to concede and returned to the Florida courts to contest Harris’s certification and to complete the recounts. Once more the presidency was in limbo, awaiting court decisions.

On December 4, Gore got two doses of bad news. The Florida circuit court had rejected his arguments for further recounts, and the US Supreme Court had vacated the Florida Supreme Court’s decision and returned it for clarification. Hesitant to intervene in the election, the justices asked the Florida court to rethink its reasons for its decision, especially in regard to the law that affected the election of electors. Most observers believed the Florida Supreme Court would alter its position and allow Bush to claim the electoral votes. Four days later, the Florida Supreme Court issued its reconsidered decision. In a 5-to-4 decision, the majority reaffirmed their earlier principle: "we must do everything required by law to ensure that legal votes . . . are included in the final election results." They ordered a state-wide manual recount of undervotes to be finished by Sunday, December 10, at 2:00 p.m. Answering the federal court’s question about authority, the majority stated that it was their "responsibility to resolve this election under the rule of law."[5] For Gore’s forces, victory might still be possible.

The celebration lasted a day as the US Supreme Court issued a 7-to-2 decision in Bush v. Gore ordering a halt to all Florida recounts and calling for arguments to reconsider the Florida court’s decisions. The oral arguments showed that the Court was divided along ideological lines. Bush’s lawyers argued that the method of the recount was "arbitrary," did "irreparable harm" to his candidacy, and violated the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Further, the Florida court’s decision violated Article 2 of the Constitution, which states that electors must be selected by a method chosen by the legislature. Gore’s lawyers responded that the recount did not injure Bush and it was best to let the people decide by counting all their votes. Most observers noted that the arguments had little chance of changing the views of the members of the Court. On December 12, the Supreme Court announced its controversial 5-to-4 decision that effectively ended all attempts to recount Florida votes and allowed Harris to ignore the already submitted recounted ballots. The decision determined that the vote certified by Harris previously (537) was correct and, above all, final. Gore conceded defeat on December 13, and five days later, George W. Bush was officially elected forty-third president of the United States as the electors cast their ballots: Bush received 271 electoral votes, one more than needed; Gore received 266.

Bush assumed office on January 20, 2001. He had lost the popular vote and many thought that if the Miami-Dade and Palm Beach recounts had been completed Gore would have won Florida’s electoral votes. Those predicting a historic election were right, but for the wrong reasons. The results were unusual but not especially historic—Republicans won the presidency and maintained control over the House, but in the Senate they had lost four seats to the Democrats, resulting in a 50/50 split. Rather, it was the intervention of the Supreme Court and the manner in which it determined the presidency that made the election so important. Many argued that the Supreme Court had lost valuable credibility, becoming too partisan, especially because the five justices (Rehnquist, Scalia, Thomas, Kennedy, and O’Connor) who most consistently sought to reduce federal authority in Supreme Court cases, had in this instance upheld federalism by overriding a state’s supreme court on the meaning and intent of a state law. President Bush would declare that he was a "uniter, not a divider," but his election highlighted partisan divisions in the nation and led to questions about the role of nation’s highest court as well as the electoral process itself.

[1] Time, November 6, 2000; Newsweek, November 6, 2000.

[2] James W. Ceaser and Andrew E. Busch, The Perfect Tie: The True Story of the 2000 Presidential Election (New York: Rowman and Littlefield, 2001), 9.

[3] Howard Gillman, The Votes That Counted: How the Court Decided the 2000 Presidential Election (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001), 20.

[4] National Review, 52 (December 18, 2000): 14.

[5] Larry D. Kramer, "The Supreme Court in Politics," in Jack N. Rakove, ed., The Unfinished Election of 2000 (New York: Basic Books, 2001), 135–136.

James Gormly is a professor of history at Washington and Jefferson College and the co-author of Making America: A History of the United States, now in its sixth edition, and author of The Collapse of the Grand Alliance, 1945–1948 (1987) and From Potsdam to the Cold War: Big Three Diplomacy, 1945–1947 (1990).

Suggested Resources

Professor Gormly suggested the following books and articles on the presidential election of 2000 and the legal challenges that emerged.

Ackerman, Bruce, ed. Bush v. Gore: The Question of Legitimacy. New Haven CT: Yale University Press, 2002.

Ceaser, James, and Andrew E. Busch. The Perfect Tie: The True Story of the 2000 Presidential Election. New York: Rowman and Littlefield, 2001.

Dershowitz, Alan M. Supreme Injustice: How the High Court Hijacked the Election of 2000. New York: Oxford University Press, 2001.

Erikson, Robert S. "The 2000 Presidential Election in Historical Perspective." Political Science Quarterly 116 (2001): 29–52.

Gillman, Howard. The Votes that Counted: How the Court Decided the 2000 Presidential Election. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001.

Myrick, Howard A. "Television’s Role in the Election of 2000." Television Quarterly 32 (2001): 14–19.

Pomper, Gerald M. "The 2000 Presidential Election: Why Gore Lost." Political Science Quarterly 116 (2001): 201–229.

Pomper, Gerard M., ed. The Election of 2000. New York: Chatham House, 2001.

Rakove, Jack. The Unfinished Election of 2000. New York: Basic Books, 2001.