The Early Republic

by Joseph J. Ellis

The Early Republic

- Creating a New Government

- The Early Republic

- The Age of Jefferson and Madison

- Hamilton

by Joseph J. Ellis

In April of 1789 the ink on the recently ratified Constitution was barely dry when George Washington began the trek from his Mount Vernon plantation to the national capital at New York. The public reverence usually accorded to royalty was on display throughout the weeklong trip, including a laurel crown lowered from an arch of triumph in Philadelphia, rose petals cast in Washington’s path by white-robed girls at Trenton, and a specially composed ode sung by a chorus of sailors in New York harbor to the tune of “God Save the King.” It was a rather courtly way to launch a republic.

When he observed “I walk on untrodden ground,” Washington was not exaggerating. The opening words of the Constitution—“We the people of the United States”—expressed a fervent hope rather than a social reality. The roughly four million settlers spread along the coastline and streaming over the Alleghenies felt their primary allegiance, to the extent they felt any allegiance at all, to local, state, and regional authorities. No republican government had ever before exercised control over a population this diffuse or a land mass this large, and the prevailing assumption among most European pundits of the day was that, to paraphrase Abraham Lincoln’s later formulation, a nation so conceived and so dedicated could not endure. The central task facing Washington and the political elite that formed around him was to prove the pundits wrong.

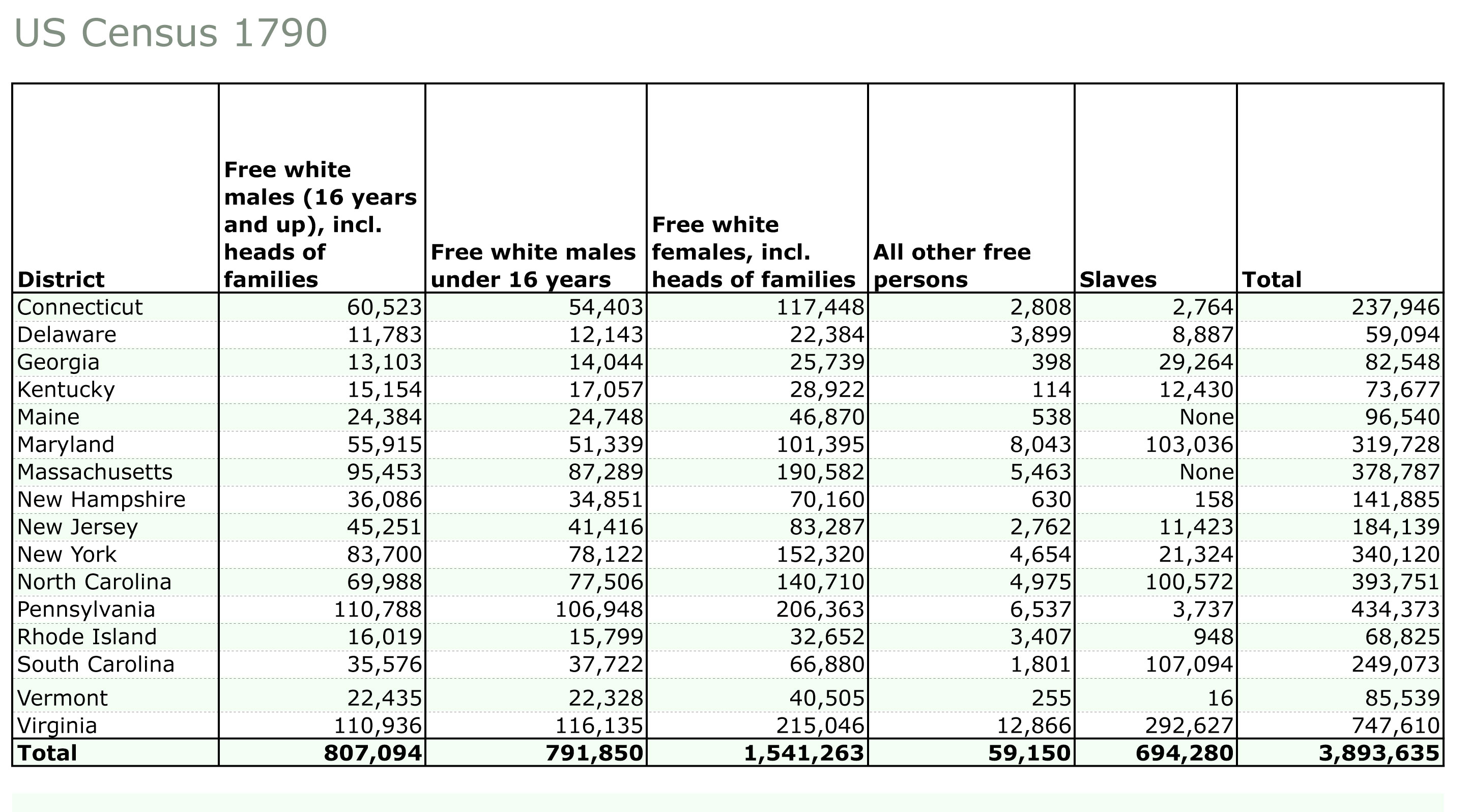

The numbers above, taken from the first census (1790), in addition to recording the size and distribution of the American population, also exposed the central dilemma destined to bedevil American politics for the next seventy years. That, of course, was slavery, which simultaneously contradicted the core principles of the American Revolution and yet dominated the demography and economy of the states south of the Chesapeake. Fully a quarter of the American population was African American, 90 percent of them enslaved, and their numbers were doubling every twenty years. Of all the problems facing the early republic, slavery posed the greatest threat to the infant American nation.

And so, with Washington’s silent endorsement, southern delegates in the First Congress, under James Madison’s adroit management, removed slavery from the federal agenda. In response to two petitions from Philadelphia Quakers calling for an end to the slave trade and a gradual emancipation to end slavery itself, the second petition signed by no less than Benjamin Franklin, the House ruled the petitions out of order on the grounds that slavery was a state matter, thereby defusing the explosive issue for the foreseeable future. The invention of the cotton gin in 1793 then extended and further imbedded slavery as the labor source in the Cotton Kingdom of the Deep South.

The census of 1790 made no mention of the approximately 100,000 American Indians, the vast majority living in about thirty tribal units between the Alleghenies and the Mississippi. A collision was clearly coming between these indigenous Americans and the tidal wave of white settlers pouring into the Ohio Valley. At the prompting of Secretary of War Henry Knox, Washington made a heroic effort to resolve the American Indian dilemma in accord with republican principles.

In the summer of 1790 he signed the Treaty of New York with the Creek Nation, which granted the Creeks sovereign control over the tribal lands in western Georgia and eastern Alabama, guaranteeing them federal protection from white settlers, who would presumably flow past this Indian enclave. Washington envisioned this treaty as the model to be followed with the other tribes, creating a series of Native American protectorates east of the Mississippi that made Indian removal unnecessary.

But it was not possible to enforce the treaty without the compliance of the state governments and a substantial increase in the size of the Army, neither of which proved possible. The result was a tragedy of epic proportions, namely genocide in slow motion.

The centerpiece of Washington’s domestic program was Alexander Hamilton’s financial plan, passed in three installments in 1790 and 1791. The flamboyant secretary of the treasury assumed responsibility for paying off the national debt, estimated at $77.1 million, and rescuing American fiscal policy from the chaos created under the Articles of Confederation. He proposed funding the national debt at par, assuming all the state debts, then establishing a national bank, forerunner of the Federal Reserve Board, to manage the economy.

Consolidating the debt and the fiscal policy at the national level made perfect sense to Hamilton, who presumed that the Constitution had vested such powers in the executive branch. But opposition to the assumption scheme, and even more so the National Bank, was fierce. Madison and Jefferson took the lead in declaring that the bank was unconstitutional and that the whole Hamiltonian program constituted a conspiracy (i.e., “the dreaded consolidation”) against the agrarian interests of the South.

At first the Virginians attempted to negotiate with Hamilton, most famously in a bargain, brokered over dinner, that traded passage of the assumption bill in return for locating the national capital on the Potomac. But after losing the battle over the bank, Madison and Jefferson went into absolute, though covert, opposition to the entire Federalist agenda. Jefferson hired the New Jersey journalist and part-time poet Philip Freneau to edit an opposition newspaper, the National Gazette, which depicted Hamilton’s financial plan as a hostile takeover of the American Revolution by “monarchists and moneymen” and accused the Federalists of attempting to recreate just the kind of British tyranny on American soil that the war for independence had supposedly banished.

This was hyperbolic rhetoric, and the suggestion that George Washington was the second coming of George III was preposterous. But in 1794, when Washington led thirteen thousand militia to western Pennsylvania to put down an insurrection by farmers protesting an excise tax on whiskey, both Jefferson and Madison described his behavior as despotic. The seeds of an organized opposition, soon to call themselves Republicans, were now planted.

Claiming to be true defenders of “the spirit of ’76” and denying with utter sincerity that they were members of a political party despite all the evidence to the contrary, the Republicans regarded any potent exercise of executive power as evidence of an American monarchy and insisted that the authority to make all domestic policy resided in the states. The clearest expression of their abiding political convictions came at the end of the decade in the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions (1798), which located sovereignty in the state and limited federal authority to foreign policy.

The chief Republican organ became the Philadelphia-based Aurora, which portrayed Washington as either a senile accomplice or a willing co-conspirator in the Hamiltonian plot to establish an American monarchy. The political atmosphere had become charged, utterly toxic, and thoroughly partisan.

Foreign policy soon became a casualty of the party wars, despite Washington’s best efforts to remain above the conflict. The central issue was the government’s posture toward the French Revolution, which after a brief romantic phase was now spiraling toward the blood-soaked guillotine. Despite nostalgic memories of France’s invaluable assistance in winning American independence, Washington was a rock-ribbed realist immune to French attachments and ideals. In 1793 he issued the Proclamation of Neutrality, declaring the Franco-American alliance (1778) void and American isolation from Europe in the long-term American interest. Jefferson argued that American ideals were its interests and that France was now the European embodiment of those ideals. The Republican press followed Jefferson’s lead and urged mass demonstrations in Philadelphia to protest Washington’s severance of the French connection.

Matters came to a head in the debate over Jay’s Treaty (1796), a hard-headed bargain with Great Britain designed to avoid war and tighten ties with America’s major trading partner. Such a diplomatic partnership with America’s implacable enemy struck most citizens as untenable, and Republican operatives had a field day denouncing the treaty as a pact with the Britannic Satan. But despite political machinations by Madison to have the decisive vote occur in the House rather than the Senate, the treaty passed by a slim majority (51-48), a tribute to Washington’s towering reputation.

Perhaps out of frustration, the Aurora launched a smear campaign against the American icon, claiming to have discovered evidence that Washington had accepted a British bribe during the war and that he had been a British spy all along. This was an outrageous libel that only exposed how poisonous American politics had become. To top it off, when Washington announced his decision to retire after two terms, which should have put the lie to Republican charges of his monarchical intentions, the Aurora urged all Americans “to devoutly pray for his imminent death.”

The election of 1796 pitted Jefferson against John Adams. The political etiquette of the era forbad campaigning, and Jefferson carried the preferred posture of indifference so far as to claim that he did not know he was a candidate. The election was extremely close (71-68) and sectional, Adams winning the North and Jefferson the South. In a quirk of the Constitution soon to be corrected, the runner-up Jefferson became vice president, making him a Trojan horse within the Adams presidency.

Few presidents in American history began their terms with greater burdens than Adams. In addition to a hostile vice president, he faced “the shadow of Washington” problem: following the greatest hero of the Revolutionary era. He also inherited Washington’s Cabinet, a second-tier group whose loyalties belonged to Hamilton. (Adams misguidedly believed that he lacked the authority to choose his own team, and there were no precedents.) The Republican press could hardly wait to level its guns on this short, stout, bald, thin-skinned New Englander, known for emotional mood swings, which were interpreted as evidence of his mental imbalance, if not insanity. Finally, he entered office with a so-called “quasi-war” raging with France, whose frigates were scooping up American merchant ships in the Caribbean in retaliation for the British tilt embodied in Jay’s Treaty.

On the positive side, Adams was perhaps the best-read student of history in the founding generation. He recognized that history’s shores were littered with the wreckage of emerging nations that foundered before they could reach maturity. He believed that Washington’s Farewell Address got it right: unity at home, neutrality abroad. He committed his presidency to ending the quasi-war with France and allowing the natural advantages of the United States to grow in splendid isolation from Europe.

To that end, in 1797 he dispatched a three-man peace delegation to Paris to negotiate a French version of Jay’s Treaty. He coupled this diplomatic commitment with a buildup of the American Navy, which would enable the United States to fight a defensive war on the high seas if the negotiations in Paris broke down.

They quickly did, and in quite spectacular fashion. Talleyrand, the famously unscrupulous French foreign minister, first refused to receive the American delegation, then sent three anonymous operatives, designated as X,Y,Z, to demand a bribe of $250,000 as a prerequisite for further negotiations. When word of this blatant skullduggery reached Philadelphia, Adams chose to keep it confidential, fearing it would provoke a popular surge in anti-French sentiment that would force the country into unnecessary war.

That almost happened when the pro-French Republicans, enjoying a two-to-one majority in the House, and suspecting Adams himself of foul play, pushed through a resolution demanding to see all the dispatches. When they exposed in excruciating detail the insulting behavior of the French government, popular opinion shifted overnight. A mob estimated at 10,000 gathered outside the presidential mansion, cheering Adams and chanting the new battle cry, “Millions for defense, not a cent for tribute.” If Adams had requested a declaration of war at that moment his popularity would have soared and his re-election been assured.

Instead, Adams made two decisions, one that placed a permanent stain on his presidency, and another that virtually assured his defeat in the next election.

The first decision, which he came to regret in his retirement, was to sign the Alien and Sedition Acts in July of 1798. These infamous statutes were designed to deport or disenfranchise foreign-born residents who were disposed to support the Republican, pro-French agenda, and make it a crime to publish “any false, scandalous, malicious writing or writings against the Government of the United States.” The Sedition Act was clearly intended to silence the barrage of anti-Adams invective pouring out of Republican newspapers like the Aurora. It was also, just as clearly, a violation of the republican principles enshrined in the First Amendment of the Constitution. Its sole redeeming feature was to make truth a defense in all libel trials, a legal precedent of considerable significance.

The second decision, made in February of 1799, was to send another peace delegation to France. The entire Federalist leadership in Congress claimed to be “thunderstruck” by the decision and began to circulate rumors that Adams had lost his mind. Adams, in fact, knew that he was committing political suicide, but when weighed in the balance against an expensive and unnecessary war with France, the decision was, as Jefferson might put it, self-evident. If virtue was the watchword of a truly republican government—and it was—Adams had committed the classic virtuous act.

The result of the presidential election of 1800 was almost foreordained, given the chasm in the Federalist camp created by the Adams decision to avoid war with France. Then Aaron Burr’s behind-the-scenes shenanigans in New York essentially bought New York’s thirteen electoral votes for Jefferson in return for a place on the ticket. The final tally (73-65) was closer than even Adams had expected. Awkwardly, Jefferson and Burr had tied, and it required thirty-six contentious ballots in the House of Representatives to make Jefferson the president. Adoption of the Twelfth Amendment in 1804 allowed electors to designate their choices for president and vice president separately, so this would not happen again.

And so as the decade, indeed the century, drew to a close, the first chapter in America’s republican experiment was ending and a new one beginning, a transition symbolized by the shift of the capital to its Potomac location, soon to be named Washington. More importantly, power had been transferred from one political party to another, all done peacefully, even routinely, according to the dictates of the Constitution.

Jefferson subsequently described his election as “The Revolution of 1800,” but in fact it was the non-revolutionary character of the transition that mattered most, suggesting as it did continuation of the ongoing experiment with republican government, an achievement that only a few developing countries over the next two centuries would be able to replicate. Jefferson gave rhetorical resonance to the abiding consensus in his inaugural address, declaring “We are all republicans – we are all federalists.” It had been a messy, bitterly partisan, highly improvisational process, but the center had held.

Joseph J. Ellis, Ford Foundation Professor of History at Mount Holyoke, is the author of Founding Brothers: The Revolutionary Generation, which received the Pulitzer Prize (2000); and American Creation: Triumphs and Tragedies of the Republic (2007).