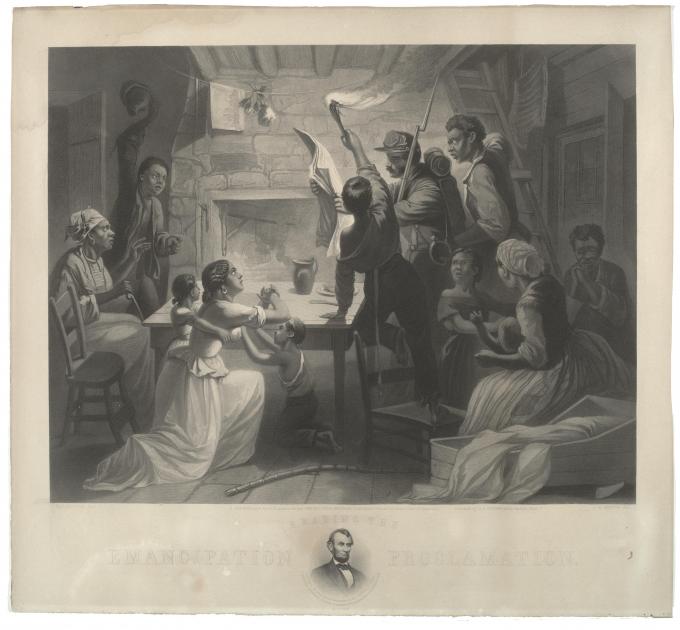

The Emancipation Proclamation: Raising money for sick and wounded soldiers

Posted by Sandra Trenholm on Monday, 11/19/2012

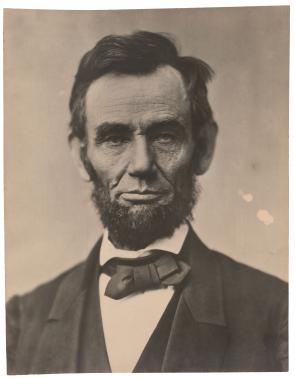

The Emancipation Proclamation stands as the single most important accomplishment of Lincoln’s presidency. The preliminary proclamation, announced on September 22, 1862, served as a warning for Southern states that if they did not abandon the war, they would lose their slaves. More important, it was the first step toward the official abolition of slavery in the United States. While many Northerners were not initially abolitionists, their support of Abraham Lincoln and the Union military, as well as the demonstrated determination of slaves to escape bondage in the South and the courage of African American soldiers, led to widening support for an end to slavery.

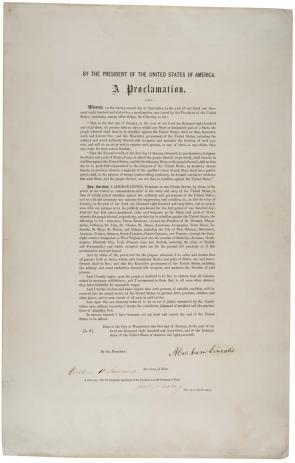

Charles G. Leland and George H. Boker prepared forty-eight copies of the Emancipation Proclamation in 1864 for sale at the Sanitary Commission’s Great Central Fair in Philadelphia. The copies, signed by Abraham Lincoln, William Seward, and John G. Nicolay (the President’s secretary) sold for $10 each. Proceeds from the fair benefited the United States Sanitary Commission, a volunteer organization that raised money to provide medicine for sick and wounded soldiers and to improved living conditions in military camps.

Charles G. Leland and George H. Boker prepared forty-eight copies of the Emancipation Proclamation in 1864 for sale at the Sanitary Commission’s Great Central Fair in Philadelphia. The copies, signed by Abraham Lincoln, William Seward, and John G. Nicolay (the President’s secretary) sold for $10 each. Proceeds from the fair benefited the United States Sanitary Commission, a volunteer organization that raised money to provide medicine for sick and wounded soldiers and to improved living conditions in military camps.

According to historian James McPherson, "Two soldiers died of disease for every one killed in battle. . . . Disease hit Civil War armies in two waves. The first was an epidemic of childhood maladies—mainly measles and mumps. . . . The second wave consisted of camp and campaign diseases caused by bad water, bad food, exposure, and mosquitoes. These included the principal killer diseases of the Civil War: dysentery and diarrhea, typhoid, and malaria." A soldier in the Civil War was ten times more likely to die of disease than a soldier in World War I. The money raised by the Sanitary Commission fairs helped ameliorate the conditions that caused disease and provided medicine and nurses to care for the sick and wounded.

The Great Central Sanitary Fair held in Logan Square in Central Philadelphia, June 7–29, 1864, has the honor of being the only event of this kind attended by President Lincoln. His speech, delivered on June 16, caused such an outpouring of emotions among the spectators that officials determined that it would be dangerous for him to attend another.

The Sanitary Commission offered an additional, often overlooked, benefit. It allowed friends and loved ones at home to feel as if they were a part of the war effort. When Northerners attended fairs, donated money or goods, or volunteered their time, they were actively aiding "their" soldier at the front.

Autographs of leading Americans were often sold at the Sanitary Commission fairs. However, only the Great Central Fair commissioned a printing of the Emancipation Proclamation.

History of the Proclamation

While the Emancipation Proclamation was conceived primarily as a military document, to withhold slave labor from the Confederate war effort, it had immediate effects in other areas. It put an end to worries over European intervention in the war on behalf of the Confederacy and boosted morale in many quarters. Southern newspapers condemned the Proclamation as a usurpation of property rights and an effort to start racial warfare.

While the Emancipation Proclamation was conceived primarily as a military document, to withhold slave labor from the Confederate war effort, it had immediate effects in other areas. It put an end to worries over European intervention in the war on behalf of the Confederacy and boosted morale in many quarters. Southern newspapers condemned the Proclamation as a usurpation of property rights and an effort to start racial warfare.

In July 1862, President Lincoln drafted a proclamation that would free slaves in the Confederacy. Lincoln first informed his Cabinet of his decision on July 22, 1862. The document stunned his Cabinet. Secretary Seward advised that the administration wait for a federal victory to issue the proclamation. With no major victories in the Eastern Theatre, the war had not gone well for the North. Seward feared the proclamation would be considered a desperate act if it were issued before the North won a major battle. Two months later, when federal troops stopped Confederate General Robert E. Lee’s invasion of Maryland at Antietam Creek, Lincoln finally had the opportunity to issue his preliminary proclamation.

During two Cabinet meetings at the end of December 1862, Lincoln listened to the criticism of the wording of his final draft. Cabinet members made suggestions for final revisions. Salmon P. Chase, Secretary of the Treasury, proposed one of the suggestions adopted by Lincoln. Chase suggested closing the document by invoking the judgment of mankind and the favor of Almighty God.

Lincoln had always believed slavery to be morally wrong and had argued against it for most of his political career. However, Lincoln knew that the president did not possess the power to abolish slavery, except as a matter of military necessity. He believed that the power to fully abolish slavery rested with Congress, and carefully worded the document to affect only those states still in rebellion as of January 1, 1863.

Now, therefore I, Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States, by virtue of the power in me vested as Commander-in-Chief, of the Army and Navy of the United States in time of actual armed rebellion against the authority and government of the United States, and as a fit and necessary war measure for suppressing said rebellion. . . . And by virtue of the power, and for the purpose aforesaid, I do order and declare that all persons held as slaves within said designated States, and parts of States, are, and henceforward shall be free; and that the Executive government of the United States, including the military and naval authorities thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of said persons.

. . . And upon this act, sincerely believed to be an act of justice, warranted by the Constitution, upon military necessity, I invoke the considerate judgment of mankind, and the gracious favor of Almighty God.

Pausing before he signed the final Proclamation, Lincoln said: "I never, in my life, felt more certain that I was doing right than I do in signing this paper."