"Dear Miss Cole": World War I Letters of American Servicemen

by Phillip Papas

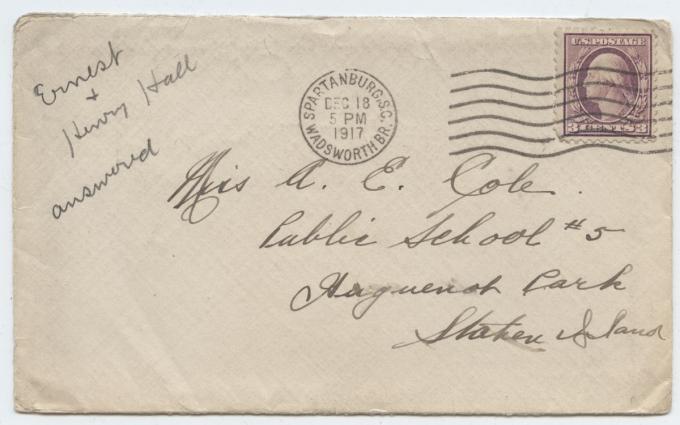

"Received your package," Pvt. George Van Pelt of Company I, 165th Infantry wrote in May 1918 from the frontlines in France to Annie E. Cole, a grammar school teacher and principal on Staten Island, New York, and to her students. "I appreciate your kindness very much and glad to know that the boys and girls of P. S. #5 have not forgotten me. Those wristlets are fine, just the thing I needed." The woman behind these letters and gifts to the soldiers, Annie E. Cole, was one of eight children born to Jacob W. and Mary Cole. After attending public schools on Staten Island and taking education courses at Columbia University, Cornell University, and Dartmouth College, she began teaching at PS #5 in the town of Huguenot Park in 1884. Annie was the school’s principal from 1891 until her retirement in 1930. Annie’s actions during the First World War embody the nationalism and spirit of volunteerism that were prevalent in America at the turn of the twentieth century. She was the head of the registration department of the Huguenot Park draft board and took part in Liberty Loan drives. Annie also volunteered for the American Red Cross and the Salvation Army, participated in the United War Work Campaign, and solicited donations for wartime relief efforts like the Armenian and Syrian Relief Fund. While Annie’s project at PS #5 might have been a lesson in communication as much as it was a gesture of patriotism, one thing is certain: it reassured the servicemen that they were not forgotten and created a bond between them and the children.

The woman behind these letters and gifts to the soldiers, Annie E. Cole, was one of eight children born to Jacob W. and Mary Cole. After attending public schools on Staten Island and taking education courses at Columbia University, Cornell University, and Dartmouth College, she began teaching at PS #5 in the town of Huguenot Park in 1884. Annie was the school’s principal from 1891 until her retirement in 1930. Annie’s actions during the First World War embody the nationalism and spirit of volunteerism that were prevalent in America at the turn of the twentieth century. She was the head of the registration department of the Huguenot Park draft board and took part in Liberty Loan drives. Annie also volunteered for the American Red Cross and the Salvation Army, participated in the United War Work Campaign, and solicited donations for wartime relief efforts like the Armenian and Syrian Relief Fund. While Annie’s project at PS #5 might have been a lesson in communication as much as it was a gesture of patriotism, one thing is certain: it reassured the servicemen that they were not forgotten and created a bond between them and the children.

For the 5,000 Staten Islanders who served stateside or in combat zones during World War I, just as for other Americans, mail was an important link to home. It helped them stay current with the activities of family, friends, and neighbors while also providing a means to communicate their experiences. Even today, with the availability of modern forms of communication such as Facebook, Skype, Twitter, and email, handwritten cards and letters as well as care packages from family, friends, and strangers provide an emotional lift for Americans in the armed forces. The servicemen’s letters to Annie E. Cole and her students, now housed at the Staten Island Historical Society, speak of patriotism, loneliness, and the emotional stress that come with combat. They bear witness to the fighting in the trenches and provide a window onto the experiences of the average American serviceman during the First World War.

With the naiveté and bravado of someone who had not yet experienced combat, Henry C. Hall, who served on the submarine chaser USS SC-147, assured Annie that the American troops would "make quick work of the Huns." Writing in November 1917, seven months after the United States entered the First World War, Hall expressed his appreciation for a care package he had received. "I want to thank both you and the children for remembering me," he wrote to Annie. "It surely is fine work that the members of P. S. 5 have started and I am sure not only myself but the rest of the boys who have joined the Colors appreciate it as well."

Pvt. George Van Pelt expected "to go in the Trenches soon" in March 1918, indicating that the men were "well trained to the new kind of warfare" and "will show our Colors believe me." Two months later, after seeing combat, Van Pelt described his experiences on the frontlines. "Well Miss Cole," he wrote, "my regiment was in action . . . [and] some of the boys met their death but the Germans paid dear for it." Van Pelt had accidentally dropped his writing paper in the trenches. "You will see there is a little mud on this paper, well that is right from the trenches of France," he explained, emphasizing his role as an eyewitness to war. "[S]how it to the class . . . [as] a souvenir from the Battlefield of France."

The tragic and exhausting conditions in the trenches come through in many of the letters home. On April 18, 1918, Pvt. Ralph M. Winant of Company F, 9th Infantry wrote: "Our organization has been at the front twice for a period of weeks and out again for what is supposed to be a rest but which, in reality, is one continuous round of work in preparation for the next time in." He added that "All of us have endured great hardships and have had to see terrible sights . . . I imagine that the idea of working in, when we come out is to keep our minds occupied so that we will not think too much about what we have seen and to make us sleep soundly." With modesty Winant declared that he did not seek accolades for his service since he was just doing "my bit . . . for the cause."

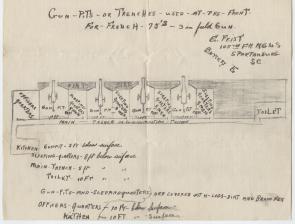

There was a limit to what the soldiers could share with Annie and her students since, for the first time in American history, soldiers’ letters were heavily censored to limit the amount of vital information that could be unintentionally leaked to the enemy. Seaman Second Class William Beyhl wanted to recount for the students of his alma mater his experiences at the American naval base in Norfolk, Virginia, but admitted that "we are not allowed to tell all we know [about] what is going on." Similarly, on July 18, 1918, Henry C. Hall wrote from Europe that he wanted to send the schoolchildren "some news direct from the old country, in regard to what is happening here but Mr. Censor doesn’t allow such news to pass so will have to wait until it can be told in person." However, one letter that evaded the censors enabled the students to better picture the trenches that stretched for miles along the battlefronts of Europe. It came from Ernest Feist, who was on maneuvers in the Blue Ridge Mountains with Battery E of the 105th Field Artillery in December 1917. Feist sent a sketch of "our gun pits for the benefit of the pupils." Their design, Feist explained, was based on "the original pits used by the French army at the front."

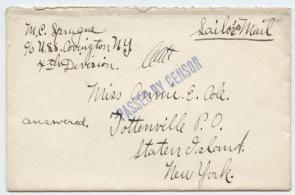

The useful objects, familiar treats, and messages of encouragement that filled care packages were lifelines for the troops. "I received your very kind gift last night and wish to thank you and your schollars very much for it," William J. Dolan, a machinists’ mate second class in the United States Naval Reserve Force, wrote on January 19, 1918. "I was just yearning for a piece of candy and your gift was a life saving." For Seaman Melvin C. Sprague, serving in France aboard the troop transport USS Covington, the "box of sweets" that he received was greatly appreciated. "It sure was a treat to have American candy to eat again, which is quite different from French," he wrote in late December 1917. In his letter of July 18, 1918, Henry C. Hall indicated that the schoolchildren’s latest care package was "the first to reach me since leaving the States" and he confessed that it was "nice . . . to receive a package from the home town when you are somewhat over five thousand miles from there."

"I was surely surprised upon receiving the package of candy and I thank you very much," wrote Richard Costello, who was with the United States Naval Reserve Force, on June 11, 1918, "for when away we greatly appreciate knowing the people at home are not forgetting us." Richard, whose full name was Clarence Richard Costello, described the excitement of mail day as the men "rush to get in line and even though sometimes we are disappointed in not getting mail we then look forward to the next mail." He added: "I was greatly pleased to think you had remembered me. For of course it was at Huguenot School I learned practically all I know." Ernest Feist’s brother Bernhard, a cadet at the quartermaster’s school located at the US Naval Training Station in Pelham Bay Park, the Bronx, New York, wrote to Annie on March 15, 1918, "You have undertaken a big job writing to all the boys & sending packages but I wish you luck also those who help. Give them my best wishes & thanks for the packages."

Long periods of separation from family and friends made it difficult for the servicemen to celebrate holidays, weddings, anniversaries, birthdays, and other personal milestones and exacerbated feelings of loneliness. In March 1918, George H. Stiles, serving on the battleship USS New Jersey, informed Annie that he had received the schoolchildren’s "thoughtful Easter box" and confessed that "getting something from home touches the heart." Melvin C. Sprague, who had been promoted to coxswain and had survived the sinking of USS Covington by a German submarine (U-86) off the coast of Brest, France, reported in November of that same year that he was "in the best of health" but confessed "I do catch the blues once in a while." For some of the servicemen being away from family for Christmas was difficult. On December 14, 1918, just over a month after the armistice of November 11 was signed, eighteen-year-old Pvt. John L. Franklin of the 423rd Company, 10th Battalion, wrote to Annie’s class from the Marine Corps training facility at Parris Island, South Carolina. "I expect to be home for Christmas," he said, but added glumly that if he did "get Christmas leave" it would be "only for two days."

The end of the war on November 11, 1918, brought joy and new challenges as well as hope and frustration to many of the servicemen. "You spoke of rejoicing, hearing that the Armistice were signed," Melvin C. Sprague wrote to Annie from the French port of Brest. "Well . . . over here . . . the people almost went crazy. There happened to be a hundred or more of Uncle Sam’s destroyers in port, which shot rockets, played search lights and blow whistles for hours." Sprague added that the "Streets were crowded with drunken Frenchmen who danced and raised old cane" while "the German prisoners here who . . . before were so sullen & slow in there work, are now full of pep and anxious to work." Writing from the German town of Bendorf on the Rhine River, in late December 1918, Ralph M. Winant, now a sergeant, described France as "badly scarred from war" and in a "deplorable state." He also noted that the Germans "are so thankful that hostilities have ceased that they are often willing to sacrifice much to add to our comfort all of which came as a surprise as we prepared to meet with all manner of unpleasantries." Winant was overcome with emotion. "After all we have been through in the last fifteen months, the greatness of this is too much . . . to grasp . . . For the first time in months we are sleeping under a roof and in a bed and get up in the morning knowing that there is plenty of water, soap and towels, whereas before we lay in little holes in the ground and wiped the mud from our faces with old papers if we had any."

At the end of the First World War, the US government began the process of demobilization and many of the troops returned to civilian life. In December 1918, Richard Costello’s brother James wrote from the army’s motor transport training center at Camp Holaird in Baltimore, Maryland: "now that . . . everything seems to be in a peaceable way . . . everyone is trying his best to get back to civilian life." James planned to resume his old job at the American District Telegraph Company when he returned to Staten Island. The words of twenty-four-year-old seaman William J. Van Pelt who, unlike his younger brother George, did not experience combat during the war, were prescient: "[T]he Germans are tricky and might only be planning for another fight in a short time."

The letters to Annie E. Cole and the schoolchildren of PS #5 on Staten Island chronicle the experiences of ordinary Americans of diverse ethnic backgrounds who were involved in an extraordinary event. They provide an enduring record of the wartime experiences of American servicemen during the First World War and demonstrate the important bonds formed between a community and its veterans. Writing to their former teacher enabled the men to open up and show their vulnerability. Their letters provide a critical glimpse of the emotional impact of war too often overlooked in discussions of combat and life in the military.

Phillip Papas is Senior Professor of History at Union County College in Cranford, New Jersey. He received his BA and MA from Hunter College and his PhD in History from the CUNY Graduate Center. He is the author of That Ever Loyal Island: Staten Island and the American Revolution (New York University Press, 2007) and Renegade Revolutionary: The Life of General Charles Lee (NYU Press, 2014). He is the co-author, with Lori R. Weintrob, of Port Richmond (Arcadia Publishing, 2009).