Lincoln and Emancipation: Black Enfranchisement in 1863 Louisiana

by Richard J. Carwardine

As the president of a fractured nation, Abraham Lincoln faced no issue more perplexing than that of restoring the rebel states to the Union. Reconstruction during wartime was, he judged, "the greatest question ever presented to practical statesmanship."[1] It meant managing a complex of competing demands: working within the Constitution, squaring local and national political demands, acknowledging military imperatives, and respecting justice for loyal Unionist southerners, white and black. Emancipation was for Lincoln an irreversible process, even in areas not covered by his Emancipation Proclamation, and freedom for the enslaved was more than a means to a restored Union: it was becoming an end in itself.

As the president of a fractured nation, Abraham Lincoln faced no issue more perplexing than that of restoring the rebel states to the Union. Reconstruction during wartime was, he judged, "the greatest question ever presented to practical statesmanship."[1] It meant managing a complex of competing demands: working within the Constitution, squaring local and national political demands, acknowledging military imperatives, and respecting justice for loyal Unionist southerners, white and black. Emancipation was for Lincoln an irreversible process, even in areas not covered by his Emancipation Proclamation, and freedom for the enslaved was more than a means to a restored Union: it was becoming an end in itself.

From the outset of the war Lincoln thought hard about restoration. He initially expected the Confederacy’s Unionists to repudiate the rebellion of what he perceived to be a self-deluding minority. In a perpetual Union, he insisted, secession could have no legal status; the rebel states remained under a federal constitution that gave the president, as commander in chief, control of wartime reconstruction policy. His duty was to nurture local initiatives toward restoring self-government and ending the rebellion. It was unlikely to involve any revolutionary tampering with southern slavery. Gradual, constitutional change offered the best hope of maintaining the political consensus essential to Union victory and a lasting peace.

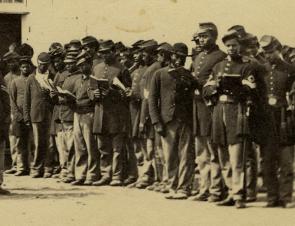

Lincoln’s early approach would eventually founder on the realities of broad-based Southern resistance, the weakness of Confederate Unionism, and the failure of the federal armies. During the summer of 1862 Lincoln concluded that emancipating secessionists’ slaves—bondage being an element vital to the South’s war effort—had come to be one of the "indispensable means" of the Union’s salvation. Invoking his constitutional power as commander in chief, the president issued a preliminary Emancipation Proclamation on September 22, and a hundred days later not only declared free the slaves in Confederate-held areas, but also opened the doors of the Union’s army and navy to the enlistment of African Americans as fighting men.

The Emancipation Proclamation heralded the death of the old Union. As the federal armies ate away at the borders of the Confederacy after New Year’s Day 1863, they became agents of liberation for the slaves who swarmed towards their approach. Both conviction and pragmatism ensured that Lincoln would hold steadfast to his new policy, though for the first half of that year he had little to show for it. The Union’s mood changed radically in the early days of July, following dramatic successes at Gettysburg and Vicksburg. Lincoln would increasingly describe his proclamation as an irreversible order, making explicit what previously he had merely implied: black freedom had become an objective of the war. "I think I shall not retract or repudiate" the proclamation, he told Stephen Hurlbut in late July. "Those who shall have tasted actual freedom I believe can never be slaves, or quasi slaves again."[2] It was a position he would reaffirm memorably at Gettysburg in November.

In the summer of 1863, Lincoln wrote a letter to three Louisiana Unionists, Thomas Cottman and two associates, that draws our attention to the local conditions prevailing in Louisiana.[3] Here in the spring of 1862 federal forces and a military governor had taken control of New Orleans and the neighboring parishes. Lincoln hoped the state’s restoration might become a model for others. The presence in the city of an educated, propertied free black population alongside one of the most substantial white Unionist communities in the lower South seemed to offer a viable nucleus for building a loyal government. But Louisiana Unionists were divided along a conservative-radical fault line over slavery’s place in the reconstituted order. Needing to hold together this coalition of proslavery planters and anti-slavery businessmen and workers, Lincoln was reluctant to see any local policy that would frighten off the conservatives, and even after issuing his preliminary emancipation order—which excluded the thirteen loyal parishes of Union-controlled Louisiana—he continued to offer "peace again upon the old terms under the constitution."[4] This, however, would depend on their moving swiftly to hold elections. A December 1862 vote in two congressional districts saw the return of two Unionist candidates, Benjamin F. Flanders and Michael Hahn. But radical Republicans, locally and in Congress, denounced the harsh "free-labor" regime which Nathaniel Banks, the commanding general, established in Louisiana to control the thousands of ex-slaves whose presence portended economic chaos, social confusion and a threat to military efficiency.

Lincoln let Banks’s contractual labor system stand. However, in the battle between Louisiana planter conservatives, who wanted to organize the state under the pre-war constitution, and the free-state men, the president’s instincts and private encouragement put him on the side of the progressives. He also wanted a "bottom-up" movement, not a Washington-imposed one. From the spring of 1863 he let it be known, discreetly, that Louisiana’s restoration would be linked to its organization as a "free state," one that had embraced emancipation. He quietly lent his support to the plan to elect a state constitutional convention that would abolish slavery. It was the proslavery opponents of the free-state men who would push Lincoln into his "first open, but indirect, indication of support for the Free State movement."[5] The planters sent a three-man delegation to the White House, led by the staunchly pro-slavery Cottman, to ask the president for "a full recognition of all the rights of the State, as they existed previous to the passage of an act of secession, upon the principle of the existence of the State Constitution unimpaired";[6] to that end they called for a November election under the old forms. Cottman judged that the president’s position on the persisting de jure authority of the federal constitution within the rebel states, and his exclusion of Louisiana parishes from the terms of the Emancipation Proclamation, meant that Lincoln would be in sympathy with the planters’ wish to see the state "return to its full allegiance" under the existing constitution.

Lincoln, however, was in no mind to fall in line. He made the delegation wait until only Cottman remained in Washington. His reply, designed for the press, explained that he was reliably informed that "a respectable portion of the Louisiana people" now sought to adopt a revised (that is, free-state) constitution: "This fact alone, as it seems to me, is a sufficient reason why the general government should not give the committal you seek, to the existing State constitution."[7] He did not go so far as publicly to endorse the free-state party. If restoration were to succeed, he needed to keep united the minority of Union men in Louisiana. But equally, he was not prepared passively to accept slavery’s perpetuation there.

What Lincoln intimated in the Cottman letter he continued to spell out privately, telling Banks in August 1863 that he did not want "to assume direction" of the state’s affairs, but that he "would be glad for her to make a new Constitution recognizing the emancipation proclamation, and adopting emancipation in those parts of the state to which the proclamation does not apply." Intimating his preference for a gentle evolution out of slavery, he continued: "And while she is at it, I think it would not be objectionable for her to adopt some practical system by which the two races could gradually live themselves out of their old relation to each other, and both come out better prepared for the new." Lincoln urged him to "confer with intelligent and trusty citizens of the State" and prepare the way for a state constitutional convention that would eliminate slavery.[8]

Having firmly told Banks to be "master" there, Lincoln felt he had to fall in with his commander’s decision to hold elections in February 1864 under the pre-war constitution. Fears that proslavery forces would secure control proved unfounded, but the convention that followed the victory of the more conservative free-state men produced a constitution too cautious for the radicals, who attacked the failure to advance beyond the promise of immediate, uncompensated emancipation and to give blacks the protection of the vote. Lincoln, though, welcomed what he judged a huge step forward, one which gave the freedmen of Louisiana greater civil and educational advantages than the blacks of his own Illinois.

He continued cautiously to move onto the radicals’ terrain. In March 1864 he urged Michael Hahn, recently elected as Louisiana’s first free-state governor, to promote a new constitution that would confer voting rights on "some of the colored people," both "the very intelligent, and especially those who have fought gallantly in our ranks." They would, he judged, "probably help, in some trying time to come, to keep the jewel of liberty within the family of freedom."[9] Just over a year later, in what turned out to be his final public address, he offered a vision of the future in which at least some blacks—including thousands who had recently been no more than illiterate field-hands—received the political rights enjoyed by whites.

The Lincoln who had never doubted that African Americans were embraced by the principles of the Declaration of Independence, but who before the war had disclaimed any intention of raising blacks to social and political equality with whites, and who had advocated the voluntary colonization of African Americans abroad, was by the time of his death meaningfully pursuing the integration of blacks into the reconstructed nation as the civic equals of whites.

[1] Inside Lincoln’s White House: The Complete Civil War Diary of John Hay. eds. Michael Burlingame and John R. Turner Ettlinger. (Carbondale, Illinois: Southern Illinois University Press, 1997), 69.

[2] Abraham Lincoln to Stephen Hurlbutt, July 31, 1863, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, ed. Roy P. Basler, 9 vols. (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1953–1955), 6: 358.

[3] Abraham Lincoln to E. E. Malhiot, Bradish Johnson, and Thomas Cottman, June 19, 1863, Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, GLC01571 (hereafter cited as GLC01571); also printed in Collected Works, 6: 287–289.

[4] Abraham Lincoln to Benjamin F. Butler, George F. Shepley and Others, October 14, 1862, Collected Works, 5:462.

[5] LaWanda Cox, Lincoln and Black Freedom: A Study in Presidential Leadership (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1981), 52.

[6] GLC01571.

[7] GLC01571.

[8] Abraham Lincoln to Nathaniel P. Banks, August 5, 1863, Collected Works, 6: 364–65.

[9] Abraham Lincoln to Michael Hahn, March 13, 1864, Collected Works, 7:243.

Richard J. Carwardine is president of Corpus Christi College, Oxford University. His biography of the sixteenth president, Lincoln (2003), received the Lincoln Prize in 2004.