Admiration and Ambivalence: Frederick Douglass and John Brown

by David W. Blight

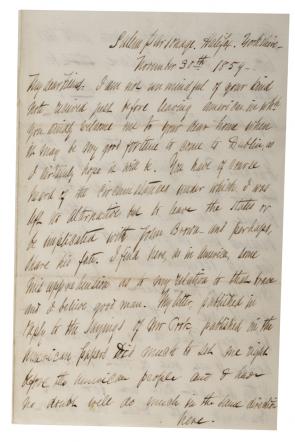

John Brown did not make it easy for people to love him—until he died on the gallows. Frederick Douglass, from his first meeting with Brown in 1847, through a testy but important relationship in the late 1850s, had long viewed the visionary abolitionist with a combination of admiration and ambivalence. In this remarkable letter (transcript) to Maria Webb—a friend in Dublin, Ireland, whom he had met in 1846–1847 and who raised money to help launch his newspaper, the North Star—Douglass defends both himself and Brown, "that brave and I believe good man." Brown’s militancy and violence against slavery had greatly influenced Douglass’s own evolving radicalism in the 1850s. However, the secrecy and strategic ineptness of the warrior from Bleeding Kansas left Douglass wary at the moment of truth when Brown had all but begged him to join the Harpers Ferry raid.

John Brown did not make it easy for people to love him—until he died on the gallows. Frederick Douglass, from his first meeting with Brown in 1847, through a testy but important relationship in the late 1850s, had long viewed the visionary abolitionist with a combination of admiration and ambivalence. In this remarkable letter (transcript) to Maria Webb—a friend in Dublin, Ireland, whom he had met in 1846–1847 and who raised money to help launch his newspaper, the North Star—Douglass defends both himself and Brown, "that brave and I believe good man." Brown’s militancy and violence against slavery had greatly influenced Douglass’s own evolving radicalism in the 1850s. However, the secrecy and strategic ineptness of the warrior from Bleeding Kansas left Douglass wary at the moment of truth when Brown had all but begged him to join the Harpers Ferry raid.

In late January 1858, Brown arrived at Douglass’s home in Rochester, New York, and stayed for a month. Living those winter days secluded in an upstairs room, Brown composed his "provisional constitution" for the state of Virginia, which he hoped to overthrow with his raid on the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia. It is likely that Brown told his host more details about his revolutionary plans than perhaps Douglass ever admitted. But the great orator-editor, who did indeed hope that Brown’s schemes might foment a successful Union-breaking assault on slavery, never found Brown’s plans, nor his leadership, convincing. Douglass did not attend Brown’s "convention" in Chatham, Ontario, on May 8, 1858, where the guerrilla leader tried to recruit African Americans to his cause. Douglass twice met Hugh Forbes, an Englishman whom Brown hired as his military strategist, when the soldier of fortune passed through Rochester in 1857–1858. Here again, Douglass was much intrigued with these clandestine plotters against slavery, but he found Forbes to be unreliable with both money and personal trust. John Brown and his plans were rays of hope and fascination, but he was hard to love.

In early fall 1859, as Brown made final preparations for his raid, Douglass, driven by curiosity and hope, paid a visit to the "old man" in Chambersburg, Pennsylvania. They met secretly in an old stone quarry, Douglass accompanied by a fugitive slave named Shields Green, whom he had brought along as a possible recruit for Brown’s band of rebels. They sat down on large rocks and discussed Brown’s plans. Brown beseeched Douglass to join his rather pathetically small band of willing warriors. "I want you for a special purpose," Douglass remembered Brown saying to him. "When I strike, the bees will begin to swarm, and I want you to help hive them." Douglass was dismayed; he had earlier understood that Brown really intended to liberate slaves in Virginia and funnel them into hideaways in the Appalachian Mountains. Now, Brown appeared obsessed with attacking the federal arsenal, a desperate mistake, in Douglass’s judgment. The former fugitive slave told the Kansas captain that he was "going into a perfect steel trap, and that once in he would not get out alive." Douglass said no to Brown’s pleas, but let Shields Green decide his own fate. According to Douglass, Green said "I b’leve I’ll go wid de ole man"; he would die at Harpers Ferry.

Meanwhile, Douglass headed north to anxiously await word of what was to come. News of an attack on October 16, 1859, against the federal arsenal at the confluence of the Potomac and Shenandoah Rivers by a band of abolitionists electrified the nation. Among the documents seized from Brown in the wake of his arrest was a brief letter to the old warrior from Douglass written in 1857. Thus, Douglass could legally be construed by outraged Virginians to have been a co-conspirator in Brown’s deeds. Douglass was in Philadelphia lecturing as news came of the raid, and he hastily took the train home to Rochester. If caught and sent to Virginia, this black abolitionist who had spent twenty years in slavery assumed that he would be killed "for my being Frederick Douglass." In the dark of night on October 22, with a warrant out for his arrest and federal marshals soon to arrive in his upstate New York hometown, Douglass took a ferry across Lake Ontario, the same route on which he had himself ushered many a runaway slave. Anxious and without options, he sailed for England in early November on a lecture trip he had already planned, but not under these circumstances. Douglass’s letter to Webb was written just two days before the dramatic hanging of Brown in a field outside Charlestown, Virginia, on December 2, 1859. He had been convicted of treason, murder, and inciting slave insurrection.

The "Mr. Cook" referred to in this letter is the twenty-seven-year-old John E. Cook, one of Brown’s men who, captured and jailed, denounced Douglass in the press for allegedly abandoning his promises to join the raid. Under this cloud of suspicion, Douglass, living in the home of his old friend Julia Griffiths Crofts and her husband, the Rev. H. O. Crofts, in Halifax, Yorkshire, felt compelled to defend himself against both the accusation of treason and of betrayal of his friends. Before leaving Canada, Douglass wrote a public letter, published in the Rochester Democrat, October 31, 1859. Sharply rejecting Cook’s denunciation, Douglass declared that he "never made a promise" to join the raid and that the "taking of Harpers Ferry was a measure never encouraged by my word or by my vote. . . . My field of labor for the abolition of slavery has not extended to an attack on the United States Arsenal." But as he made a case for his legal innocence, he also embraced violence and declared himself very much John Brown’s moral ally.

This became a common position among many abolitionists, and even some Republican party politicians. "I am ever ready to write, speak, publish, organize, combine, and even to conspire against slavery," said Douglass, "when there is a reasonable hope of success. Men who live by robbing their fellow-men of their labor and liberty have . . . voluntarily placed themselves beyond the laws of justice and honor, and have become only fitted for companionship with thieves and pirates." Douglass wanted it widely known that he objected only to Brown’s particular means and tactics, not his ultimate ends or his justification. Even Harriet Beecher Stowe had demonstrated in Uncle Tom’s Cabin that lawlessness was the abolitionists’ necessary weapon. The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 had made virtually all radical abolitionists law-breakers. Douglass was willing to be lawless, willing to kill "pirates." But he knew that such acts against slavery and its national police power in America required more than courage and justification; it would take extraordinary cunning, skill, mobilization, and military prowess.

Douglass returned to America from England in early summer 1860, drawn home by the news that his beloved daughter Annie had died that spring at age eleven. As the election year intensified, the federal government ceased its pursuit of Brown’s alleged accomplices among abolitionists. Douglass came back to a grief-stricken family and a nation on the brink of disunion. In his personal arsenal of rhetorical weapons against slavery, and soon the Confederacy, would always be John Brown’s dead body. Hard to love in life, Brown was of enormous value in death. Douglass saw Brown’s enduring worth to the cause of black freedom, and he never ceased to eulogize the martyr, the classical hero, whose sacrifice made his gallows as sacred as the Christian cross.

In an 1881 speech at Storer College, in Harpers Ferry, Douglass declared that the hour of Brown’s "defeat was the hour of his triumph," his "capture" the "victory of his life." As though remembering his own ambivalence about Brown’s plans in 1859, but also the power of his symbol in the wake of the execution, Douglass summed up the old warrior’s significance. "With the Allegheny mountains for his pulpit, the country for his church and the whole civilized world for his audience," announced Douglass, "he was a thousand times more effective as a preacher than as a warrior." Brown had used revolutionary violence, however ineptly, to foment a larger revolution in America. For that, Douglass would forever honor him as the greatest abolitionist hero. At some of Douglass’s speeches recruiting black soldiers during 1863, he would break into "John Brown’s Body," singing as he called young men forward in the fight to destroy slavery. Brown had become not only loveable, but a "soul" that kept a cause alive and marching in dark times to come.

David W. Blight is Class of 1954 Professor of American History at Yale University and Director of the Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance, and Abolition at Yale. He is the author of A Slave No More: Two Men Who Escaped to Freedom, Including Their Narratives of Emancipation (2007); Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory (2001), which received the Bancroft Prize, the Abraham Lincoln Prize, and the Frederick Douglass Prize; and Frederick Douglass’s Civil War: Keeping Faith in Jubilee (1989).