"Hidden Practices": Frederick Douglass on Segregation and Black Achievement, 1887

by Edward L. Ayers

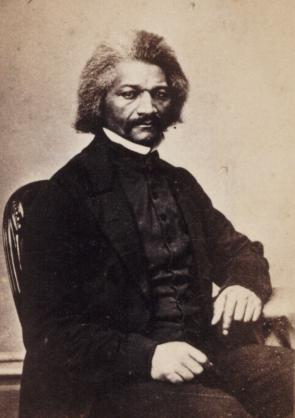

Frederick Douglass recalled his feelings when slavery came to an end, after so much work and so many sacrifices. "I felt that I had reached the end of the noblest and best part of my life," he admitted. But Douglass hardly underestimated the challenges facing the four million people emancipated in part by his labors. Even during the Civil War, he foresaw that "sullen, silent, and gloomy but subdued hate shall settle upon the Southern mind." In the face of what was sure to be white resistance to every step of black freedom, "a profounder wisdom, holier zeal, than belongs to the prosecution of war, will be required."

Frederick Douglass recalled his feelings when slavery came to an end, after so much work and so many sacrifices. "I felt that I had reached the end of the noblest and best part of my life," he admitted. But Douglass hardly underestimated the challenges facing the four million people emancipated in part by his labors. Even during the Civil War, he foresaw that "sullen, silent, and gloomy but subdued hate shall settle upon the Southern mind." In the face of what was sure to be white resistance to every step of black freedom, "a profounder wisdom, holier zeal, than belongs to the prosecution of war, will be required."

Once freedom came, Douglass offered surprising counsel to northern whites who asked what should be done "with the Negro": "Do nothing with us! . . . All I ask is, give him a chance to stand on his own legs! Let him alone!" Douglass wanted black southerners simply to have a fair chance. He wanted them to be treated like other Americans, with equality in the courts, at the polls, and in the marketplace. Douglass felt confident that black Americans would succeed if they had the opportunity.

Fittingly, Douglass’s major theme in the lectures he gave in the postwar era was "Self-Made Men." He gave that speech fifty times, before every kind of audience. The talk echoed the themes of his great speeches of the antebellum years, when he told the story of his own self-fashioning as he made himself free. Douglass saw the harsh trials of the post-Reconstruction South as a test for black Americans, a crucible in which their greatness would be forged. He wanted his fellow black citizens to prove themselves, without aid and without excuse. Poverty stood as the greatest enemy of African Americans, he told a black audience in the middle of Reconstruction, because poverty "makes us a helpless, hopeless, dependent, and dispirited people, the target for the contempt and scorn of all around us." As soon as black Americans could display a "class of men noted for enterprise, industry, economy and success," he assured another African American audience, "we shall no longer have any trouble in the matter of civil and political rights." In his emphasis on individual accomplishment and on the power of the marketplace as the ultimate judge of worth, Douglass shifted the responsibility on to black shoulders. His words, perhaps to our surprise, sound more like Booker T. Washington than W. E. B. Du Bois.

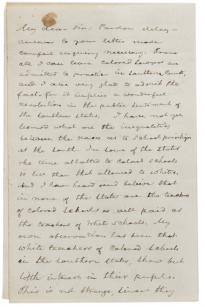

Douglass’s consistent view of black progress is clearly on display in a letter from 1887. Use the opportunities before you, it counsels its unknown recipient, and have confidence that effort and experience will succeed. A "wonderful revolution in the public sentiment of the Southern states" had taken place because black lawyers were permitted to practice in Southern courts, Douglass heard.

In the schools of the South, though, he reported, African American people faced discrimination in funding; as a result, black schools suffered from shorter days and lower-paid teachers. Douglass wanted black teachers for black schools, fearing that the only whites who would teach black students were forced to do so by "their necessities" rather than by dedication.

In this letter, so balanced between hopefulness and despair, Douglass observes that "Our wrongs are not so much now in written laws which all may see—but the hidden practices of a people who have not yet abandoned the idea of Mastery and dominion over their fellow man." Unfortunately, the ideas of mastery and dominion were soon to take legal form. White southerners, worried that their control was being eroded by the very forces of black advancement Douglass celebrated, began to create an elaborate system of laws "for all to see," that instituted white determination to sustain "dominion over their fellow man." Even as Douglass wrote this letter, legislators across the South were forging laws of segregation and disfranchisement that would shackle the South for generations to come. In the late 1880s, unsatisfied with leaving black people alone and seeing them prosper, white southerners segregated one public space after another and systematically undermined black voting.

Frederick Douglass, speaking in the determined language of American self-help, did not anticipate such a campaign against black people, brought on by the fears their very success unleashed. But, in his remaining years, he would fight against discrimination just as he had fought against slavery, as a violation of American ideals.

Edward L. Ayers is president emeritus of the University of Richmond, where he is currently the Tucker-Boatwright Professor of the Humanities. He has authored or edited ten books, several focused on the history of the American South and the legacy of the Civil War, including The Promise of the New South: Life after Reconstruction (1992); In the Presence of Mine Enemies: Civil War in the Heart of America, 1859–1863 (2003), which received the 2004 Bancroft Prize for Distinguished Book in American History; and America’s War: Talking about the Civil War and Emancipation on their 150th Anniversaries (2011).