Getting Ready to Lead a World Economy: Enterprise in Nineteenth-Century America

by Joyce Appleby

When Jefferson won the presidency in 1801, his victory had an economic impact as great as the political one. The establishment of the new government under the Constitution twelve years earlier had laid the foundation for an integrated market, but its character remained to be shaped. At the center of this critical economic moment were the competing visions of Jefferson and the Federalists.

When Jefferson won the presidency in 1801, his victory had an economic impact as great as the political one. The establishment of the new government under the Constitution twelve years earlier had laid the foundation for an integrated market, but its character remained to be shaped. At the center of this critical economic moment were the competing visions of Jefferson and the Federalists.

Many of those supportive of the Constitution hoped that the country might grow more like Great Britain with its stability, refinement, and deference to leading families. But an unexpected opposition arose over just these goals, sparked by battles over free speech, democratic participation, and grassroots opportunity. Upon winning the election in 1800, Jefferson swiftly dismantled the Federalists’ fiscal program, reducing taxes and halving the size of the civil service that Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton had built up to provide energy and direction from the political center. Yet under the aegis of the Federalists, roads were constructed, debts paid off, postal services extended, customs established, and newspapers promoted. And thanks to Hamilton’s fiscal prowess, the United States became a safe place to stash money.

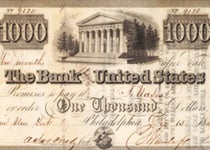

Most Europeans who bought Hamilton’s stock invested their earned interest in the country’s many private ventures. America became the first emerging market. Had the Federalists passed on their power to like-minded men in 1801, the course of economic development would have been guided by government officials attentive to the nation’s major creditors. A national elite would have informed policies for the country as a whole. The Bank of the US would have controlled the flow of credit, and the pace of settlement would have slowed as land passed first to large speculators. Since the Federalists considered the differences between the talented few and the ordinary many as fixed by nature, they favored concentrating capital in the hands of those who knew best how to invest it.

Instead, a new political movement explicitly hostile to the exercise of government authority triumphed. The fiscal stability that Hamilton had achieved benefited the very people who fought to liberate themselves from men like him. The United States in fact got the best of two worlds in Hamilton and Jefferson. Even though Hamilton dismissed the notion that ordinary people could use their money wisely—and thus ignored the most protean element in the economy—he won the confidence of investors at home and abroad. Jefferson, on the other hand, distrusted financiers and wanted to free ordinary white men from the condescension of their superiors. He released the pent-up energies of thousands who hungered for inclusion in the economic potential that all could see. His belief in limiting government power also had roots in the slaveholders’ determination not to be harassed by the federal government. And he was lucky enough to pass on his policies to his two successors and neighbors. Freed from British restrictions, American merchants sent ships up the California coast, across the Pacific, and into the Indian Ocean. Elias Hasket Derby, America’s first millionaire, made his money opening up markets in Russia and the Orient. American boat designers and shippers had the pleasure of beating out the English with clippers built up and down the New England coast. Pushing the rivalry a bit further, American merchants began sending their ships to China to deliver tea to the London market, prompting a great competition.

While President Jefferson was popularizing a political movement to give autonomy to ordinary people, Chief Justice John Marshall was working to weaken local authority. Marshall made decisions to uphold contracts and block state-sanctioned monopolies, clearing the ground for a particularly individualistic kind of capitalism. Although they were rivals inappreciative of each other’s talents, Marshall developed a liberal jurisprudence that complemented Jefferson’s executive initiatives. Strengthening the constitutional protection of contracts and property, the Supreme Court reduced the scope of both federal and state legislative power. Capitalism was made safe for democracy, and democracy itself came to mean protection of individual rights more than the power of the people to act through their representatives. For the next half century the states, shorn of the power to block economic development, took the lead in promoting it. They built an infrastructure of banks, roads, and canals while offering bounties, licenses, and charters for promising and unpromising ventures alike. The last Federalist institution, the Bank of the United States, hit the dust in 1836 with Andrew Jackson’s determination to strangle "the monster bank." It obviously was unnecessary to economic development since those years saw phenomenal growth.

Entrepreneurial Americans didn’t want financial order; they wanted easy credit and money to fund their enterprises. If this meant repeated panics and bubbles, as it did, they accepted them as the price of free enterprise. In the United States the freedom to innovate, to move up and out, to make it on one’s own acquired an enhanced value. Capitalist development did not seem a divisive force to ordinary Americans, but rather the main vehicle of progress for an energetic, disciplined, self-reliant people. Americans identified their nation with commercial prowess in a way that was unthinkable in any other country. This appreciation of economic growth erected a high ideological barrier to collective action whether it came from laborers trying to unionize or reformers securing social benefits for the population as a whole.

If the Constitution laid the bedrock of America’s liberal society, the free enterprise economy raised its scaffolding. The elimination of imperial control over land and credit enabled thousands of operators to act on their plans with the financing of high hopes. Old colonial wealth rarely went into new enterprises after independence. Small, start-up firms using waterpower in rural areas initiated new manufacturing ventures with borrowed money and their own sweat equity. Like ordinary farmers buying land on credit, they took their lumps during market downturns. There was little of the spirit of noblesse oblige among them. They developed a "pull yourself up with your own boot straps" attitude toward success and failure.

Fortuitously, this spirit of initiative was accompanied by successful efforts to join the Union by roads and canals and still later, telegraph and railroads. Congress also promoted informal unity with its expanding postal service and by underwriting the mailing costs of the country’s proliferating newspapers. Americans were buying 22 million copies of 376 papers annually by 1810, the largest aggregate circulation of newspapers of any country in the world. Ten years later, the number of newspapers published had more than doubled and so had the size of the reading public. Ludwig Gall, a German traveler, noted that even female street vendors and free blacks read the newspaper. Once controlled by the elite, information and opinions had been wrested away by the elite’s articulate critics.

Simultaneously, a never-ending stream of Americans, eager for farms of their own, pushed west with confidence that they had a right to the land. Acquisition had to be bought, negotiated for, or taken from tribes that had lived there for centuries. "Hostile" became linked to the word "Indians." Newspapers characterized the Native Americans’ tenacious fight to save their ancestral grounds as savagery. The number of property owners increased with the opening up of public land for bargain purchases after 1801. While many remained poor farmers, they had managed to get on the right side of the critical divide between independence and dependency. After the War of 1812, Congress gave its veterans 160-acre bounties in land lying between the Illinois and Mississippi Rivers. When land offices opened on the frontier, sales soared. Frontier communities sprouted up like daisies in a summer meadow. The invaders justified their intrusion on the grounds that the indigenous people had failed to improve the land, or at least improve it in the European manner. Capitalism, with its steady promotion of development, gave a kind of specious justice to Americans’ advance into the wilderness. Skirmishes and set battles between the invaders and defenders continued throughout the settlement of the Ohio and Mississippi Valleys.

American geographic mobility astounded foreign visitors who wrote home about the undulating train of wagons snaking their way to Pittsburgh from where they could raft down the Ohio. To these visitors, American society offered an ever-changing visual landscape as people moved, roads were graded, land cleared, and buildings razed in a reconfiguration of the material environment that went on without rest. Ordinary men had never before had such a chance to create their own capital. Yet it was slave-produced cotton that brought the big profits to the country. As northerners moved into Ohio, Illinois, Michigan, Iowa and Michigan, southern planters took their slaves into Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana. Although all of the northern states had found ways to put slavery on the path toward abolition by 1801, any hopes that slavery might come to an end in the nation as a whole died with the expansion of the South’s frontier. The value of slaves started a steady ascent with Eli Whitney’s cotton gin, which made profitable the short staple cotton that could be grown everywhere. Returns from selling cotton abroad helped settle the country’s international debts and put money in the pockets of northerners who catered to the planters’ need for clothing and cloth, furniture and furnishings, and tools and trinkets.

Fueling this slave-based prosperity was the industrial revolution that had started in England. Steam engines revolutionized old ways of mining, shipping, and making everything from tools to pottery. But its greatest impact was on the manufacturing of cloth. Rarely has an invention come at a more opportune moment. British textile mills, soon to be joined by domestic producers, couldn’t get enough cotton. Southern specialization made planters dependent on the North for foodstuffs, lumber products, and manufactured goods. Producing cheap shoes and clothes for slaves became a start-up venture for many a bootstrap entrepreneur. Against the measurable wealth that slave labor created, the South experienced an immeasurable loss of cultural capital in skills not learned and investment opportunities left undeveloped. Less tangible was the enormous drain of the region’s moral resources from defending a social system that others found increasingly indefensible.

Who was the new American entrepreneur? With few exceptions, he came from a growing middle class distinguished from wealthy, colonial families by its work ethic and openness to new ideas. He borrowed from friends and family, invested his own sweat equity, and sank or swam with regularity. With such volatility, "panics" and "busts" came every score of years. The human loss in dollars and disappointments was significant, but the young economy was resilient enough to snap back. Many a poor white boy—sometimes even a girl—discovered his talent for making clocks, buttons, industrial wire, textiles, shoes, hats, pianos, vulcanized rubber, and steam engines of various kinds. The market’s opportunities came in new guises to new participants. The digest of patents put out by the first commissioner reveals the full sweep of commercial imagination. Because America’s patent law was cheaper and easier to acquire, ordinary people took advantage of its protection. As rural towns connected to the national market through roads, canals, and railroads, patent applications dramatically increased. Scores of ordinary Americans patented devices in metallurgy, chemical processes, hydraulic implements, machine tools, and household conveniences. After 1834 the US Patent Office scrutinized applications for novelty and usefulness. While this move diminished the number of patents granted, it also proved a boon to unknown and under-funded inventors whose success in getting a patent acted as a vote of confidence for the invention.

The national market became even more vitally connected in 1835 when Samuel Morse demonstrated that signals could be transmitted by wire. More specifically, electric impulses could be sent from an apparatus connected by an electric circuit to a receiver that operated an electrical magnet to produce marks on paper. From this, Morse composed his famous code of dots and dashes representing letters of the alphabet. Morse’s telegraph became the most widely used and an integral part of running a railroad. In the United States, railroads were seen as so essential to national unity that the federal government lent its Army engineers to lay out the first routes. (West Point was in fact the major engineering school in the country at the time.) Once established, maintaining railroads called for continuous experimentation to improve roadbeds and rails. Morse’s invention speedily shuttled information about arrivals, departures, and breakdowns across continents. Telegraph poles lined the roadbeds, vivid evidence that the space dividing people was collapsing.

In 1865, the New York Central Railroad alone had assets equal to one-quarter of all American manufacturing wealth. The substantial capital fixed in railroad lines forced investors to keep the volume of traffic as high as possible, introducing the new constraints of industrial capitalism. The impact of railroads on the overall economy went from transportation to production to finance. Railroads became integral to the business plans of others—not just manufacturers but farmers as well, all of whom were highly sensitive to rate schedules or any shenanigans that might be used to raise rates. Railroads quickly became a kind of public utility that eventually prompted government regulation.

American industry was on the march. By 1836, domestic locomotives supplanted British ones. In 1856, domestic production of iron overtook imports. The volume of American steam power surpassed that of Great Britain in 1850 and far outdistanced it by 1870. By 1886, United States steel production eclipsed that of Great Britain. One English traveler noted that he had never "overheard Americans conversing without the word dollar being pronounced." It didn’t matter, he said, whether the conversation took place "in the street, on the road, or in the field, at the theatre, the coffee-house or at home." Washington Irving had coined the phrase "the almighty dollar" in the 1820s. A century later, President Calvin Coolidge famously announced that "the business of America is business." For the United States, the push to advance economically became an intrinsic part of its emerging national character. Americans celebrated their enterprise and efficiency as a way to differentiate themselves from decadent, feudal Europe. Bereft of any strong aristocratic traditions, they valued the audacious qualities of their entrepreneurs.

In the 1850s, the world economy got a phenomenal boost after James Marshall discovered gold at his sawmill. Just nine days later the United States signed the treaty that ended the Mexican-American War and gave the nation California. The volatility of a gold find in an area not yet outfitted with the clothes of government produced a unique situation. Fortune hunters sped to California. Within four years, a quarter of a million immigrants from twenty-five countries had arrived. Indigenous men and women died in great numbers at the hands of lawless and racist newcomers. More gold was dug up in the 1850s than all places put together in the previous 150 years. World trade almost tripled, lubricated by an influx of gold that increased the world’s currency sixfold. Gold surpassed silver as the standard currency.

Meanwhile, the high costs of fighting a Civil War enabled Congress to support a network of federally chartered banks that could issue notes. A provision was built in: the banks had to deposit their cash reserves in New York City. As a result, New York City became the country’s financial center. As the Civil War raged, the pace of economic change accelerated. For decades prior to the war, cotton exports had dominated the American economy, orienting northern agriculture and industry toward southern consumption. During the war, the Union Army’s demand for uniforms, tents, rifles, wagons, and foodstuffs took hold. This new market acted like a catalyst in the industrialization of the economy.

After the war, the party of Lincoln became the party of nascent industrialists. Yet with individuals and private companies acting on what they calculated as their best interest, it was difficult to know what was going on. In a free enterprise system guided by dispersed decision-making, no one was in charge. The year 1873 proved to be disastrous in the history of American capitalism. A depression began that lasted in some areas for another twenty-six years. The crisis of 1873 illustrated the integration of world markets when downturns in the United States and Europe plagued economies in South Africa, Australia, and the West Indies.

When the price of silver began to fluctuate wildly in 1870s, the awkwardness of using both silver and gold as currency became apparent. Great Britain had maintained a single source of value, gold, to settle accounts; the United States and other countries followed suit in the 1870s. Now each country’s currency—mark, franc, pound, dollar—had a fixed exchange rate with gold. The gold standard proved to be an invisible taskmaster, nanny, jailer, and seer. It influenced everything from imports and exports to the price of wages. If a country ran a trade deficit, gold left the country causing a drop in the domestic purchasing power, which in turn hurt sales. Manufacturers had to lower costs to regain customers. They generally did this by pushing down wages.

The gold standard marked a new intensification of global trade greatly aided by telegraphy, international business news, and improved oceanic transportation. People became more confident that their money would be fairly exchanged in other countries; they started investing abroad, and especially in the United States—now the largest economy and the land of the best opportunities for high returns on capital.

By 1870, the last of the southern states had been readmitted into the union, and the North was ready to call it quits on reconstructing the states that had joined the Confederacy. Turning toward the West, Congress passed the Indian Appropriation Act of 1871 that made Native Americans national wards and nullified all previous Indian treaties. With the completion of the transcontinental railroad, the victorious North was ready to impose its national vision upon both the South and the West. The United States was now in a position to lead the world’s economy for the next hundred and fifty years. Its federal government had reestablished its authority; its Atlantic and Pacific coasts were joined by railroads. Its industry was about to pull in twenty million immigrants, mainly from central and eastern Europe. Grains from the "fruited plains" of California and the Midwest fed a burgeoning population of 76 million at century’s end. Despite efforts to organize labor, the industrialists and their bankers were firmly in charge of the economy and visible signs of its progress dominated public consciousness.

Joyce Appleby is Professor of History Emerita at the University of California, Los Angeles. Her most recent book is The Relentless Revolution: A History of Capitalism (2010).