Editor’s Log

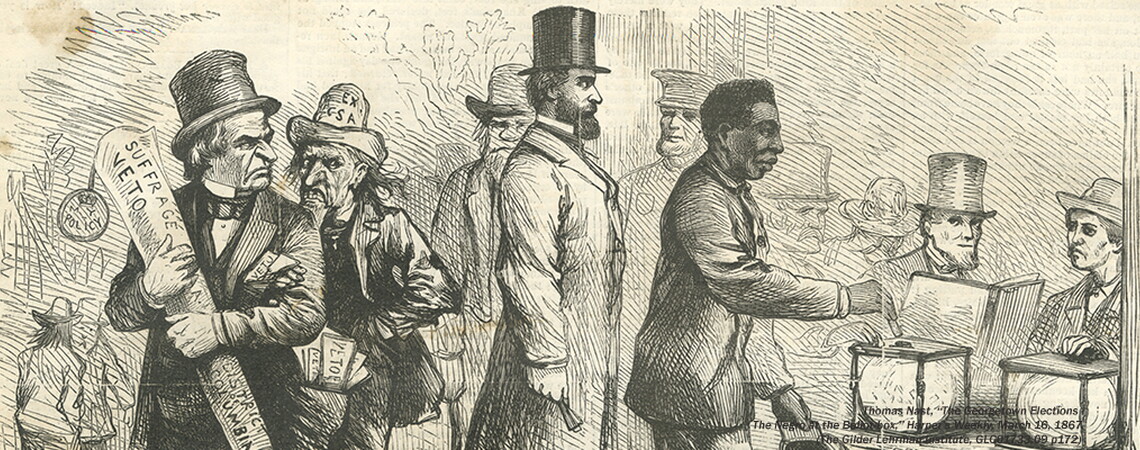

If the Civil War preserved the Union, then Reconstruction grappled with what that Union was to look like in the future. The Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments to the Constitution, passed in the years immediately after the war, signaled that the country was proceeding on a radical vision of racial equality. That this vision soon faded—only to be revived again in the century that followed, even as it came to include gender issues, is the subject of this issue of History Now. In the pages that follow, historians seek to provide us with a better understanding of the context of the constitutional amendments, their immediate consequences, and their persistent promise. These essays look at the violent response to Reconstruction, but also at the unexpected results of well-meaning efforts to insure civic equality. Finally, they explore the responses of a wide variety of Americans—African Americans, Native Americans, women, and former Confederates—to the radical changes promised by the postwar amendments. The result is a rich issue of our journal, filled with material you can bring into the classroom.

In our lead essay, “Reconstruction and the Remaking of the Constitution,” the premier scholar in the field, Eric Foner, provides a masterful overview of the era and its legacy. The three amendments that defined Reconstruction should be seen, he writes, as a “second founding,” a constitutional revolution that offered a new definition of the rights of all Americans. Foner proceeds to examine the origins, enactments, and objectives of these amendments and the contest over their meaning, a contest that continues to this day. This essay is strong in insight and serves as a reminder of the links between our national past and our national present.

Douglas Egerton heightens our understanding of African American goals and interpretations of Reconstruction’s promise in his essay, “Frederick Douglass and the Dawn of Reconstruction.” Douglass believed that Reconstruction did not begin with legislation; it began with the participation of black soldiers in the Union army. “No power on the earth,” Douglass declared, could deny the right of citizenship to any man who risked his life in the army of his country. Like Douglass, other African American leaders argued that Reconstruction was not simply a project for the former Confederacy; it was a mission to transform the entire nation. If many white abolitionists believed their work was done once slavery was ended, these black activists knew that, as Egerton puts it, “the antithesis of slavery was not freedom, but equality.”

Richard White, a leading expert on the history of the American West, views the goals of Reconstruction from a different perspective. In “Reconstructing the West and North,” White argues that Congressional radicals intended to redefine citizenship as “homogeneous,” that is, as the enjoyment of identical rights for all citizens. But when this concept was applied to Indian Country in the West and to the immigrant populations of Northern cities, homogeneity also meant that the citizens themselves would be diverse. Unity among these diverse peoples would come, the radicals believed, when all Americans adopted the values of the “heartland”—rural, small town communities. As White shows us, this insistence that the farm and the farm family should be the model for the nation’s citizens led to unexpected and often negative consequences.

In her essay, “Citizenship in the Reconstruction South,” Susanna Lee explores the racist views that sustained the institution of slavery and that shaped the mindset of the former political leadership of the Confederacy. Like other modern historians, Lee addresses the active role freed men and women played in the struggle to define the contours of a biracial democracy. She shows us the connection between the racial attitudes and the gender assumptions of elite white southerners, a link that helped insure that no effective women’s rights movement could take root in the reconstructed South.

In our final essay, “The Rise (and Fall) of the First Ku Klux Klan,” Elaine Frantz Parsons describes the origins of this terrorist organization and its activities in the Reconstruction era. Established by six men in Pulaski, Tennessee in 1866, the Klan spread rapidly throughout the Southern states. Its purpose was to secure white supremacy and to put an end to African American movement toward economic independence, social equality, and political organization. Parsons details the varieties of intimidation and violence perpetrated by the Klan against black people and the efforts by freed women and men to defend themselves against these attacks. She points out that both the federal government and state governments sought to police the Klan’s behavior by passing the federal Enforcement Acts and state laws that made it illegal to wear disguises in public. By the time of the 1872 elections, the Klan’s violence had, in fact, receded, but white southerners continued to rely on threats and violence in later years. Parsons reminds us that in 1915, the Klan would resurface again.

In addition to these essays, this issue includes a special feature: a video of Henry Louis Gates, Jr., speaking at Pace University to an audience of Gilder Lehrman Affiliate School teachers and students about his acclaimed 2019 book, Stony the Road: Reconstruction, White Supremacy, and the Rise of Jim Crow.

The issue also offers a lesson plan for grades 9−12 by Rosanne Lichatin, the 2005 National History Teacher of the Year, on Lincoln and Reconstruction, as well as a selection of relevant Spotlights on Primary Sources from the Gilder Lehrman Collection.

In this issue, we have drawn on the historical lessons learned by Gilder Lehrman staff in Montgomery, Alabama, on November 1–3, 2019. On this staff trip, twenty-two GLI employees had the opportunity to visit major sites in the city, including the Rosa Parks Museum, the Legacy Museum, and the National Memorial for Peace and Justice. The Memorial commemorates more than 4,000 African Americans who were lynched in the US from 1877 to 1950—a long period of terror and violence between Reconstruction and the Civil Rights Movement. It is critically important for the Gilder Lehrman Institute to ensure—in this issue of History Now and in all the work we do for teachers and students—that the story of racial injustice is fully and unflinchingly told, and that the legacy of courageous Americans who fought for equality is both furthered and commemorated.

We hope that the information and analyses offered by distinguished historians and educators will enable you, as teachers, to enrich your classroom lessons on this critical period in our national history.

Carol Berkin, Editor

Presidential Professor of History, Emerita, Baruch College & The Graduate Center, CUNY

Nicole Seary, Managing Editor

Senior Editor, The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History

Special Features

A book talk by Henry Louis Gates, Jr., Alphonse Fletcher University Professor and Director of the Hutchins Center for African and African American Research, Harvard University, on Stony the Road: Reconstruction, White Supremacy, and the Rise of Jim Crow (Penguin, 2019), an event sponsored by the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History and attended by New York City student groups at the Schimmel Center, Pace University, May 31, 2019.

“Civil War and Reconstruction, 1861–1877,” an illustrated timeline

From the Archives

Videos

“The Importance of Frederick Douglass,” a presentation by David W. Blight, Sterling Professor of American History, Yale University

“1866: The Birth of Civil Rights,” a presentation by Eric Foner, De Witt Clinton Professor Emeritus of History, Columbia University

“The Politics of Reconstruction,” a presentation by Eric Foner, De Witt Clinton Professor Emeritus of History, Columbia University

“Reconstruction and Citizenship,” a presentation by Eric Foner, DeWitt Clinton Professor Emeritus of History, Columbia University

“The Changing Views of Reconstruction,” a presentation by Eric Foner, DeWitt Clinton Professor Emeritus of History, Columbia University

“Reconstruction and Its Legacy,” a presentation by Eric Foner, De Witt Clinton Professor Emeritus of History, Columbia University

“Inside the Vault: A Threat from the KKK, 1868,” a presentation by Beth Huffer, Former Curator of Books and Manuscripts, The Gilder Lehrman Collection

“Frederick Douglass on Lincoln and Reconstruction,” a presentation by Matthew Pinsker, Pohanka Chair in American Civil War History, Dickinson College

Essays

“Reconstruction” by Edward L. Ayers, Tucker-Boatwright Professor of the Humanities and President Emeritus, University of Richmond

“A Right Deferred: African American Voter Suppression after Reconstruction” by Marsha J. Tyson Darling, History Now 51, “The Evolution of Voting Rights,” Summer 2018

“Civil War and Reconstruction, 1861−1877” by Eric Foner, DeWitt Clinton Professor Emeritus of History, Columbia University

From the Teacher’s Desk (Lesson Plans)

“Lincoln’s Reconstruction Plan” by Rosanne Lichatin (Grades 9−12)

Spotlights on Primary Sources (Please make sure you are logged in to see these pages.)

“The women’s rights movement after the Civil War, 1866,” a primary source by Mary Tillotson

“Charles Sumner on Reconstruction and the South, 1866,” a primary source by Charles Sumner

“Sharecropper contract, 1867,” a primary source by Isham G. Bailey, Cooper Hughs, and Charles Roberts

“‘The war ruined me’: The aftermath of the Civil War in the South, 1867,” a primary source by A. C. Ramsey

“A Ku Klux Klan threat, 1868,” a primary source by a “Ku Klux”

“The Fifteenth Amendment, 1870,” a primary source by William Henry Seward

“Racism in the North: Frederick Douglass on ‘a vulgar and senseless prejudice,’ 1870,” a primary source by Frederick Douglass

“Frederick Douglass on Jim Crow, 1887,” a primary source by Frederick Douglass

“Frederick Douglass on the disfranchisement of black voters, 1888,” a primary source by Frederick Douglass

“A former Confederate officer on slavery and the Civil War, 1907,” a primary source by John S. Mosby