Historical Context: Facts about the Slave Trade and Slavery

by Steven Mintz

TRANS-ATLANTIC SLAVE VOYAGES

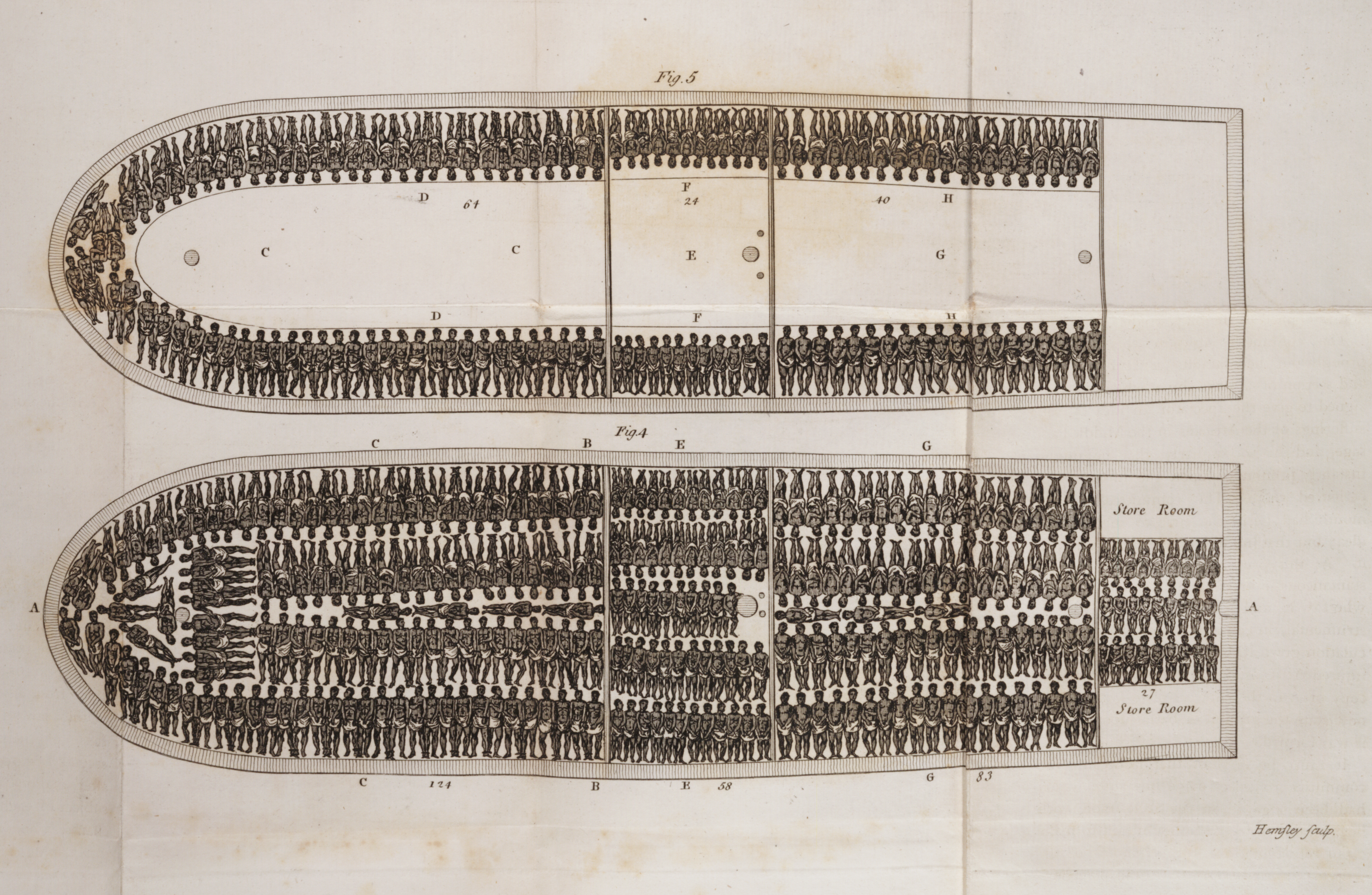

Over the period of the Atlantic Slave Trade, from approximately 1526 to 1867, some 12.5 million captured men, women, and children were put on ships in Africa, and 10.7 million arrived in the Americas. The Atlantic Slave Trade was likely the most costly in human life of all long-distance global migrations.

The first Africans forced to work in the New World left from Europe at the beginning of the sixteenth century, not from Africa. The first voyage carrying enslaved people direct from Africa to the Americas probably sailed in 1526.

The number of people carried off from Africa reached 30,000 per year in the 1690s and 85,000 per year a century later. More than eight out of ten Africans forced into the slave trade crossed the Atlantic between 1700 and 1850. The decade 1821 to 1830 saw more than 80,000 people a year leaving Africa in slave ships. Well over a million more—one-tenth of those carried off in the slave trade era—followed within the next twenty years.

By 1820, nearly four Africans for every one European had crossed the Atlantic; about four out of every five women who crossed the Atlantic were from Africa.

The majority of enslaved Africans brought to British North America arrived between 1720 and 1780.

Africans carried to Brazil came overwhelmingly from Angola. Africans carried to North America, including the Caribbean, left mainly from West Africa.

Well over 90 percent of enslaved Africans were sent to the Caribbean and South America. Only about 6 percent of African captives were sent directly to British North America. Yet by 1825, the US population included about one-quarter of the people of African descent in the Western Hemisphere.

The Middle Passage was dangerous and horrific. The sexes were separated; men, women, and children were kept naked, packed close together; and the men were chained for long periods. About 12 percent of those who embarked did not survive the voyage.

US SLAVERY COMPARED TO SLAVERY IN THE AMERICAS

Plantations in the United States were dwarfed by those in the West Indies. In the Caribbean, many plantations held 150 enslaved persons or more. In the American South, only one slaveholder held as many as a thousand enslaved persons, and just 125 had over 250 enslaved persons.

In the Caribbean, Dutch Guiana, and Brazil, the enslaved death rate was so high and the birth rate so low that they could not sustain their population without importations from Africa. Rates of natural decrease ran as high as 5 percent a year. While the death rate of the US enslaved population was about the same as that of Jamaican enslaved persons, the birth rate was more than 80 percent higher in the United States.

In the United States enslaved persons were more generations removed from Africa than those in the Caribbean. In the nineteenth century, the majority of enslaved in the British Caribbean and Brazil were born in Africa. In contrast, by 1850, most US enslaved persons were third-, fourth-, or fifth-generation Americans.

Slavery in the US was distinctive in the near balance of the sexes and the ability of the enslaved population to increase its numbers by natural reproduction. Unlike any other enslaved society, the US had a high and sustained natural increase in the enslaved population for a more than a century and a half.

CHILDREN

There were few instances in which enslaved women were released from field work for extended periods during slavery. Even during the last week before childbirth, pregnant women on average picked three-quarters or more of the amount normal for women.

Infant and child mortality rates were twice as high among enslaved children as among southern White children. Half of all enslaved infants died in their first year of life. A major contributor to the high infant and child death rate was chronic undernourishment.

The average birth weight of enslaved infants was less than 5.5 pounds, considered severely underweight by today’s standards.

Most infants of enslaved mothers were weaned within three or four months. Even in the eighteenth century, the earliest weaning age advised by doctors was eight months.

After weaning, enslaved infants were fed a starch-based diet, consisting of foods such as gruel, which lacked sufficient nutrients for health and growth.

HEALTH AND MORTALITY

Enslaved persons suffered a variety of miserable and often fatal maladies due to the Atlantic Slave Trade, and to inhumane living and working conditions.

Common symptoms among enslaved populations included blindness, abdominal swelling, bowed legs, skin lesions, and convulsions. Common conditions among enslaved populations included beriberi (caused by a deficiency of thiamine), pellagra (caused by a niacin deficiency), tetany (caused by deficiencies of calcium, magnesium, and Vitamin D), rickets (also caused by a deficiency of Vitamin D), and kwashiorkor (caused by severe protein deficiency).

Diarrhea, dysentery, whooping cough, and respiratory diseases as well as worms pushed the infant and early childhood death rate of enslaved children to twice that experienced by White infants and children.

DOMESTIC SLAVE TRADE

The domestic slave trade in the US distributed the African American population throughout the South in a migration that greatly surpassed the Atlantic Slave Trade to North America.

Though Congress outlawed the African slave trade in 1808, domestic slave trade flourished, and the enslaved population in the US nearly tripled over the next fifty years.

The domestic trade continued into the 1860s and displaced approximately 1.2 million men, women, and children, the vast majority of whom were born in America.

To be “sold down the river” was one of the most dreaded prospects of the enslaved population. Some destinations, particularly the Louisiana sugar plantations, had especially grim reputations. But it was the destruction of family that made the domestic slave trade so terrifying.

PROFITABILITY

Prices of enslaved persons varied widely over time, due to factors including supply and changes in prices of commodities such as cotton. Even considering the relative expense of owning and keeping an enslaved person, slavery was profitable.

In order to ensure the profitability of enslavement and to produce maximum “return on investment,” slaveholders generally supplied only the minimum food and shelter needed for survival, and forced their enslaved persons to work from sunrise to sunset.

Although young adult men had the highest expected levels of output, young adult women had value over and above their ability to work in the fields; they were able to have children who by law were also enslaved by the owner of the mother. Therefore, the average price of enslaved females was higher than their male counterparts up to puberty age. Men around the age of 25 were the most “valuable.”

Slaveholding became more concentrated over time, particularly as slavery was abolished in the northern states. The fraction of households owning enslaved persons fell from 36 percent in 1830 to 25 percent in 1860.

During the Civil War, roughly 180,000 Black men served in the Union Army, and another 29,000 served in the Navy. Three-fifths of all Black troops were formerly enslaved.

WORKS CITED AND RESOURCES

University of Virginia, American Slave Narratives

The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database, Emory University

The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, Or Gustavus Vassa, The African (1789)

Special thanks to Steven Mintz, University of Texas at Austin