“Defence of Fort McHenry” or “The Star-Spangled Banner,” 1814

A Spotlight on a Primary Source by Francis Scott Key

In September 1814, Francis Scott Key, an attorney and DC insider, watched the American flag rise over Baltimore, Maryland’s Fort McHenry from a British ship in the harbor. Key had been negotiating the release of an American captive during the War of 1812 when the British attacked the fort. After twenty-five hours of heavy bombardment, Key was sure that, come dawn, the British flag would be flying over Baltimore. Upon seeing the American flag still aloft, he wrote, on the back of a letter, the first verse of what would eventually become the national anthem of the United States. Once he returned to the city, he drafted three more verses, completing what was then titled “Defence of Fort M‘Henry.” The words were put to the tune of a popular British song, “To Anacreon in Heaven.”

“Defence of Fort M’Henry” grew to be one of the most recognized songs in the United States. A local printer first published the lyrics in a broadside and shortly after, two Baltimore newspapers picked it up as well. By October, seventeen newspapers had spread the song up and down the East Coast. Within a few months, the song’s title, “Defence of Fort M’Henry,” was replaced with its more recognizable name, “The Star-Spangled Banner.” (It is believed that Thomas Carr, a Baltimore publisher, coined the new title.) In the 1890s, the US Navy and Army made “The Star-Spangled Banner” an official song of the military. President Woodrow Wilson signed an executive order to make it the national anthem for the military in 1916, and in 1931, Congress passed legislation making it the national anthem.

“Defence of Fort M’Henry” grew to be one of the most recognized songs in the United States. A local printer first published the lyrics in a broadside and shortly after, two Baltimore newspapers picked it up as well. By October, seventeen newspapers had spread the song up and down the East Coast. Within a few months, the song’s title, “Defence of Fort M’Henry,” was replaced with its more recognizable name, “The Star-Spangled Banner.” (It is believed that Thomas Carr, a Baltimore publisher, coined the new title.) In the 1890s, the US Navy and Army made “The Star-Spangled Banner” an official song of the military. President Woodrow Wilson signed an executive order to make it the national anthem for the military in 1916, and in 1931, Congress passed legislation making it the national anthem.

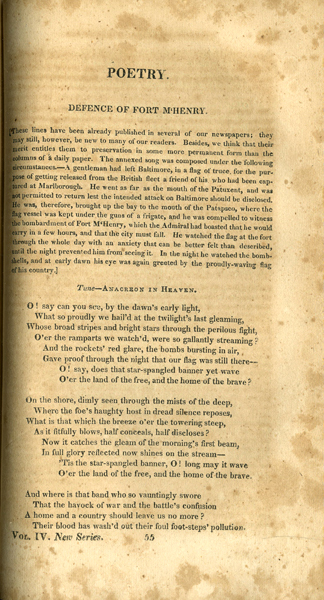

This document, “Defence of Fort M’Henry,” is from the Analectic Magazine, published by Moses Thomas in Philadelphia. This publication includes all four verses of the song, including the controversial lines in the third verse, “No refuge could save the hireling and slave, From the terror of flight or the gloom of the grave.” Key was most likely referring to the more than 4,000 enslaved people who joined the Corps of Colonial Marines during the War of 1812 to fight for the British to gain their freedom. Some printed editions of the song omit that verse altogether. The Analectic Magazine’s introduction hints at the song’s rapid rise in popularity, saying, “These lines have already been published in several of our newspapers. . . . We think that their merit entitles them to preservation in some more permanent form than the columns of a daily paper.”

Excerpts

[Verse 1]

O! say can you see, by the dawn’s early light,

What so proudly we hail’d at the twilight’s last gleaming,

Whose broad stripes and bright stars through the perilous fight,

O’er the ramparts we watch’d, were so gallantly streaming?

And the rockets’ red glare, the bombs bursting in air,

Gave proof through the night that our flag was still there—

O! say, does that star-spangled banner yet wave

O’er the land of the free, and the home of the brave?

[Verse 3]

And where is that band who so vauntingly swore

That the havock of war and the battle’s confusion

A home and a country should leave us no more?

Their blood has wash’d out their foul foot-steps’ pollution.

No refuge could save the hireling and slave,

From the terror of flight or the gloom of the grave;

And the star-spangled banner in triumph doth wave

O’er the land of the free, and the home of the brave.