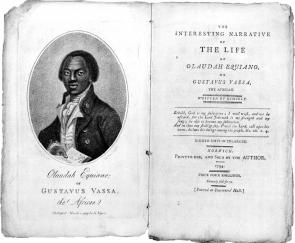

Olaudah Equiano, 1789

A Spotlight on a Primary Source by Olaudah Equiano

Within ten years of the first North American settlements, Europeans began transporting captured Africans to the colonies as enslaved laborers. Imagine the thoughts and fears of an eleven-year-old boy who was kidnapped from his village by African slave traders. He was forced to march west to the coast of Africa, sold to different people along the way. When he reached the Slave Coast he saw White men for the first time. His mind must have been filled with many questions. Where was he going? What would these men do to him? Would he ever see his home again?

Within ten years of the first North American settlements, Europeans began transporting captured Africans to the colonies as enslaved laborers. Imagine the thoughts and fears of an eleven-year-old boy who was kidnapped from his village by African slave traders. He was forced to march west to the coast of Africa, sold to different people along the way. When he reached the Slave Coast he saw White men for the first time. His mind must have been filled with many questions. Where was he going? What would these men do to him? Would he ever see his home again?

This young man was Olaudah Equiano. He and many other Africans, both male and female, were loaded on ships that took them to the British colonies, where they were sold as slaves. Hundreds of people were packed into the lower decks with barely enough room to move during a journey that took at least six weeks. Many died, but Equiano survived.

Equiano traveled the world with his enslaver, a ship captain and merchant. In 1766 he was able to purchase his own freedom. Equiano wrote his autobiography, The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa, the African, in 1789. Equiano recounted how his early life in Africa was interrupted when he was kidnapped by slave traders and separated from his family, writing “we were soon deprived of even the smallest comfort of weeping together.” Equiano was bought and sold, marched to the African coast, and shipped in squalid conditions to America. He wrote of the voyage, “The closeness of the place, and the heat of the climate, added to the number in the ship, which was so crowded that each had scacely room to turn himself, almost suffocated us.” Many people read Equiano’s Narrative, and his account exposing the horrors of slavery influenced Parliament’s decision to end the British slave trade in 1807.

Excerpt

I was not long suffered to indulge my grief; I was soon put down under the decks, and there I received such a salutation in my nostrils as I had never experienced in my life; so that with the loathsomeness of the stench, and crying together, I became so sick and low that I was not able to eat, nor had I the least desire to taste any thing. I now wished for the last friend, Death, to relieve me; but soon, to my grief, two of the white men offered me eatables; and, on my refusing to eat, one of them held me fast by the hands, and laid me across, I think, the windlass, and tied my feet, while the other flogged me severely. I had never experienced any thing of this kind before; and although not being used to the water, I naturally feared that element the first time I saw it; yet, nevertheless, could I have got over the nettings, I would have jumped over the side; but I could not; and, besides, the crew used to watch us very closely who were not chained down to the decks, lest we should leap into the water; and I have seen some of these poor African prisoners most severely cut for attempting to do so, and hourly whipped for not eating. This indeed was often the case with myself. In a little time after, amongst the poor chained men, I found some of my own nation, which in a small degree gave ease to my mind. I inquired of them what was to be done with us? they gave me to understand we were to be carried to these white people’s country to work for them.