The Chinese Exclusion Act, 1882

A Spotlight on a Primary Source by the US Congress

Signed into law on May 6, 1882, the Chinese Exclusion Act barred most Chinese immigration to the United States by placing a 10-year ban on the entry of Chinese laborers. Chinese merchants, diplomats, scholars, and students were exempt from the ban. However, the law required them to obtain certification from the Chinese government before emigrating, which created a new barrier to entry into the country. The act also prohibited Chinese immigrants and their US-born children already living in the United States from becoming citizens, thus excluding them from the electorate.

Signed into law on May 6, 1882, the Chinese Exclusion Act barred most Chinese immigration to the United States by placing a 10-year ban on the entry of Chinese laborers. Chinese merchants, diplomats, scholars, and students were exempt from the ban. However, the law required them to obtain certification from the Chinese government before emigrating, which created a new barrier to entry into the country. The act also prohibited Chinese immigrants and their US-born children already living in the United States from becoming citizens, thus excluding them from the electorate.

In 1892, the ban was extended for another ten years, and in 1902 it was extended indefinitely. Congress repealed the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1943. However, the race-based quota system established by the 1924 National Origins Act greatly limited immigration from countries outside of northern and western Europe. In effect, only 105 people of Chinese ancestry were permitted entry to the US each year. It was only in 1965, with the passage of the Immigration and Nationality Act, also known as the Hart-Celler Act, that immigration quotas were eliminated, and Chinese were permitted to immigrate in the same numbers as people from other countries.

The Chinese Exclusion Act was the nation’s first race-based immigration law. It was also the most restrictive immigration act to that date. While the act created unprecedented restrictions and paved the way for further discrimination in immigration law, Chinese immigrants impacted by the act did not passively accept discrimination. Some challenged it through the court system, while others found ways to circumvent it. Between 1882 and 1905, more than 10,000 lawsuits relating to Chinese immigration and civil rights were filed, including the landmark Supreme Court case United States v. Wong Kim Ark (1898), which ensured that Chinese born in the United States were guaranteed citizenship through the American citizenship clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. The “paper son” system, in which young Chinese men tried to gain entry using purchased identity papers that falsely claimed they were the sons of US citizens, became a common method of bypassing the restrictions.

A full transcript is available.

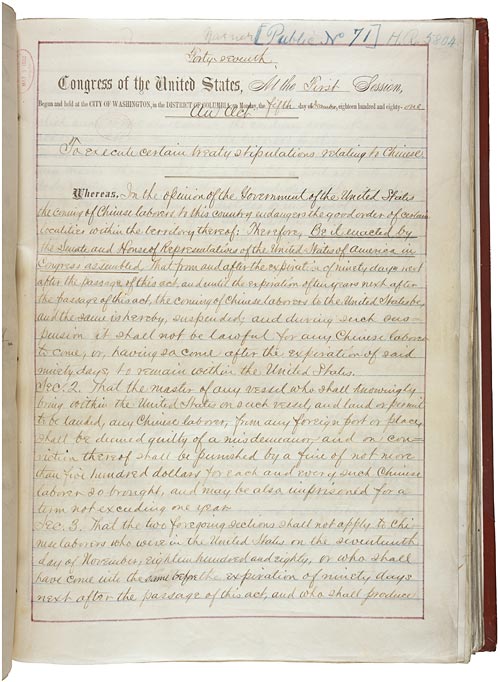

Excerpt

An act to execute certain treaty stipulations relating to the Chinese, May 6, 1882

Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, That from and after the expiration of ninety days next after the passage of this act, and until the expiration of ten years next after the passage of this act, the coming of Chinese laborers to the United States be, and the same is hereby, suspended; and during such suspension it shall not be lawful for any Chinese laborer to come, or, having so come after the expiration of said ninety days, to remain within the United States. . . .

SEC. 14. That hereafter no State court or court of the United States shall admit Chinese to citizenship; and all laws in conflict with this act are hereby repealed.

SEC.15. That the words “Chinese laborers”, wherever used in this act shall be construed to mean both skilled and unskilled laborers and Chinese employed in mining. . . .