Revolutionary in America

by Ray Raphael

The image is so clear in our minds, seen first in elementary school and reinforced countless times since: a few dozen gentlemen with powdered wigs and period suits (coats, waistcoats, and knee-length breeches) gathered in a large meeting room, some standing and some sitting, but all up to something important. Visually, John Trumbull’s painting of the Declaration of Independence is not exactly lively, but we know and cherish the story it signifies—our Founding Fathers pledging their lives, fortunes, and sacred honor in support of independence. It was the nation’s founding moment.

The image is so clear in our minds, seen first in elementary school and reinforced countless times since: a few dozen gentlemen with powdered wigs and period suits (coats, waistcoats, and knee-length breeches) gathered in a large meeting room, some standing and some sitting, but all up to something important. Visually, John Trumbull’s painting of the Declaration of Independence is not exactly lively, but we know and cherish the story it signifies—our Founding Fathers pledging their lives, fortunes, and sacred honor in support of independence. It was the nation’s founding moment.

Eleven years later there would be another grand moment, in the exact same chamber. With no famous portrait to consult, we conjure our own sensory images. We know it was stifling hot within that closed-up room, the windows and shutters sealed to keep the proceeding secret. We imagine the perspiration flowing as our Founding Fathers (a mostly different set this time, although we rarely take note of that) devised a Constitution to guide the fledgling nation.

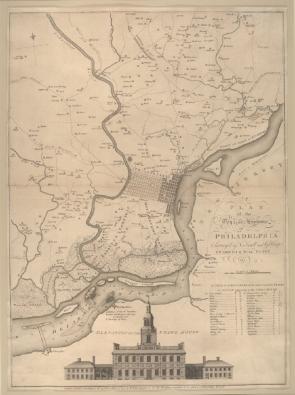

These two interior scenes define a nation, a city, and a time: the United States of America, as created in Philadelphia in 1776 and 1787. We know and cherish the city for what it has given us. But what of the city itself, outside that forty-foot square chamber in the East Wing of the Pennsylvania State House?

Philadelphia in those days was the commercial and cultural hub of the British colonies. During the boom stimulated by the French and Indian War, it had surpassed Boston as North America’s largest city. Streets were paved with stone and met each other at proper right angles. (The streets in Boston and New York, by contrast, had evolved from cow trails.) Wagons, drays, coaches, chariots, and chaises carried freight and passengers over the cobbles, while pedestrians strolled on flat brick sidewalks. Since 1752, the city had even been lit at night. Three-story houses butted against each other, crowding out untamed nature. For its residents, Philadelphia appeared a haven of European-styled "civilization" at the edge of a large, and largely unknown, continent.

Philadelphia in those days was the commercial and cultural hub of the British colonies. During the boom stimulated by the French and Indian War, it had surpassed Boston as North America’s largest city. Streets were paved with stone and met each other at proper right angles. (The streets in Boston and New York, by contrast, had evolved from cow trails.) Wagons, drays, coaches, chariots, and chaises carried freight and passengers over the cobbles, while pedestrians strolled on flat brick sidewalks. Since 1752, the city had even been lit at night. Three-story houses butted against each other, crowding out untamed nature. For its residents, Philadelphia appeared a haven of European-styled "civilization" at the edge of a large, and largely unknown, continent.

Within this city, Independence Hall (as we now call the State House) was not the only venue to host the American Revolution. There were several others, such as:

The Waterfront. This was the lifeblood of the city. From Philadelphia’s docks, the produce of interior regions was loaded onto oceangoing vessels, in exchange for rum, molasses, and a wide assortment of manufactured goods from Europe. To the docks came wave after wave of indentured servants, and some African slaves as well. Philadelphia was the "New York" of the time, a rich melting pot of ethnicities and nationalities that made it a truly cosmopolitan city. Since much of colonial discontent centered on issues of trade, the waterfront became a battleground of sorts. In the late 1760s, when American patriots agreed not to import British goods, artisans, who supported local manufactures, rubbed against wealthy merchants, who relied heavily on British trade. In 1773, when the East India Company tried to dump its surplus tea on the American market, patriots patrolled the shores of the river, waiting to turn the tea ships away.

Market Square. At the junction of Second Street and High (now called Market Street), an open swath of cobblestone was bordered by the Court House, the Greater Meeting House, and long rows of covered market stalls. It was here the local militiamen mustered and trained, ready to defend their city.

Workshops. During the third quarter of the eighteenth century, Philadelphia’s "mechanics," people who worked with their hands for a living, developed a will of their own. Rising in opposition to the "better sort" who controlled the provincial government, they challenged local hierarchies and British oppressions simultaneously. One group was particularly instrumental in fomenting unrest: printers. Through newspapers and broadsides, patriots preached and planned a formidable resistance movement. Early in 1776, local printers produced an inflammatory pamphlet called Common Sense, written by a recent immigrant from England, a failed stay-maker named Tom Paine.

Public houses (taverns). In Philadelphia, as elsewhere in the colonies, men who drank together found it easier to suspend the customary patterns of deference. Raising toast after toast, they encouraged each other to take the next step on the path to rebellion. The London Coffee House (drinks there were not limited to coffee) played host to a group of radical activists who planned numerous mass meetings. At the City Tavern, the plushest of the lot, delegates to the Continental Congress dined and caucused. In taverns throughout the city, men read aloud and debated the ideas presented in Common Sense.

Carpenters’ Hall. In the early 1770s, the Philadelphia Carpenters’ Company, the oldest craft guild in America, constructed its own meeting space, a handsome structure, less ornate than the State House, that housed several important gatherings. As soon as the building was completed, Ben Franklin moved his Library Company upstairs; there, people not only read but also talked about philosophy and politics.

- On September 5, 1774, in the large meeting room downstairs, the First Continental Congress held its opening session. Members of the conservative Pennsylvania Assembly had offered to host Congress at the State House, but most delegates felt more comfortable talking about resistance in a venue not formally tied to the British Crown. While seated in personalized chairs made by local craftsmen, delegates decided to support and coordinate the resistance.

- In June of 1776, a different sort of revolution was fomented in Carpenters’ Hall. By that time, most Pennsylvanians and most Americans had come to favor independence, but the Pennsylvania Assembly instructed its delegates in the Continental Congress to oppose it. The best way to counter the Assembly, radical patriots reasoned, was to supplant it with a new governmental body, authorized by a new Constitution. And so it was that in Carpenters’ Hall, a Provincial Congress organized a separate Constitutional Convention for Pennsylvania. That summer, meeting in the West Wing of the State House, across the hall from the Continental Congress, the Convention passed the most democratic of all state constitutions. All power was vested in a single legislature, directly responsible to the people. Meetings were open to the public. All proposed bills had to be printed and disseminated, and none could be passed until the following session, after the people themselves had had a chance to debate the issue.

State House Yard. Outside the State House, in an area originally defined by the Pennsylvania Assembly as "a public open green and walk for ever," common citizens during Revolutionary days gathered in extralegal "town meetings" to debate the issues of the day and take decisive actions. For instance:

- On October 5, 1765, several thousand citizens pressured the Stamp Act collector to forsake his duties.

- On July 30, 1768, another large crowd voiced its support for the Massachusetts Assembly, which had just been disbanded because it defied royal authority.

- On December 27, 1773, an estimated 8,000 people voiced their support for the Boston Tea Party. A ship bearing tea had just anchored downriver in the Delaware, and the people warned its captain, who had been ushered into town, that the "Committee of Tarring and Feathering" had prepared for him some "Pitch and Feathers," should he attempt to land the tea. (He chose instead to return to Britain, his cargo unloaded.)

- On June 18, 1774, several thousand people met once again at the State House Yard to endorse the idea of a Continental Congress, call for a Provincial Conference to choose delegates, and set up a Committee of Correspondence for the city of Philadelphia.

- On April 25, 1775, as soon as the news of Lexington and Concord arrived in town, nearly 8,000 men gathered and "unanimously agreed to associate [take up arms], for the purpose of defending their Property, Liberty and Lives."

- On May 20, 1776, despite a driving rain, 4,000 people decided to replace the conservative Assembly and set up a new government. (This meeting led to the gathering of delegates from across Pennsylvania in Carpenters’ Hall the following month, the Constitutional Convention in July, and finally the ultra-democratic Pennsylvania Constitution, as described above.)

- On July 8, 1776, "a great concourse of people" gathered in the State House Yard to hear the first public reading of the Declaration of Independence. After three rounds of spirited "huzzahs," some of the crowd entered the State House and tore down the King’s Arms. Come evening, under a clear, starry sky, people lit bonfires and rang bells and generally caroused about town.

- On June 21, 1783, several hundred soldiers from the Pennsylvania Line met in the yard and surrounded the State House, demanding their pay from the Continental Congress, which was meeting inside. Although British rule was over, the practice of public demonstrations for redress of grievances continued.

All this is not to diminish the importance of what happened in the East Wing of the State House in 1776 and 1787, but only to provide a wider context for those grand events.

On June 7, 1776, Richard Henry Lee of Virginia introduced a motion in Congress: "Resolved, That these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States, that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain is, and ought to be, totally dissolved." Three weeks earlier, the Virginia Convention had called upon its congressional delegates to introduce just such a resolution, yet delegates from several other colonies still opposed independence, and some were under specific instructions from their provincial assemblies to vote against it. Rather than force the issue immediately, Congress tabled the matter till July 1.

Back home in the colonies, the people went to work. Pennsylvania’s new Provincial Convention issued instructions to vote for independence. So did several county conventions in Maryland, the colony that had been most fervently in opposition. On June 28, the Maryland Convention voted unanimously for independence. Immediately, Samuel Chase wrote triumphantly to John Adams: "See the glorious Effects of County Instructions. Our people have fire if not smothered."

On the morning of July 1, just as Congress resumed debate on Lee’s motion, Chase’s letter was delivered to Adams within the East Wing chamber. Maryland was in tow, but Pennsylvania’s delegates were still divided, some answering to the instructions of the Assembly and others to the Provincial Convention. By the next day, however, the Pennsylvania delegation had made its decision: by a vote of three-to-two, with two delegates abstaining, Pennsylvania supported independence, as did twelve of the thirteen colonies. (The delegates from New York abstained, for they had been instructed not to vote either way.)

And so it was, on July 2, 1776, a new nation was born. Two days later, Congress approved its formal Declaration of Independence. Today, we celebrate the document; back then, the fact of independence counted for more than its representation. On July 3, before the Declaration had been finalized, John Adams wrote to his wife Abigail: "The second day of July, 1776, will be the most memorable epocha in the history of America. I am apt to believe that it will be celebrated by succeeding generations as the great anniversary festival. It ought to be commemorated as the day of deliverance, by solemn acts of devotion to God Almighty. It ought to be solemnized with pomp and parade, with shows, games, sports, guns, bells, bonfires, and illumination, from one end of this continent to the other, from this time forward forevermore" (The Book of Abigail and John: Selected Letters of the Adams Family, 1762–1784 [Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1975], 142).

Many teachers and students of American history have read or heard Adams’s prediction, which has proved correct in everything but the date. Less known, but more significant, is his description in the same letter of the political process that culminated in independence: "Time has been given for the whole people maturely to consider the great question of independence, and to ripen their judgment, dissipate their fears, and allure their hopes, by discussing it in newspapers and pamphlets, by debating it in assemblies, conventions, committees of safety and inspection, in town and county meetings, as well as in private conversation, so that the whole people, in every colony of the thirteen, have now adopted it as their own act."

Adams knew, and we should too, that what transpired within the Pennsylvania State House had been made possible by the revolution that was happening in many other locales and venues.

The context for the Constitutional Convention in 1787 was altogether different. The meeting then was not influenced by mass rallies at the State House Yard, thousands of conversations in taverns, or resolutions passed in meeting houses across the land. Instead, it was an inside job, the result of politicking by smart and influential men who desired a stronger government—politically, financially, diplomatically, and militarily—than the existing Articles of Confederation could deliver.

The tone was more conservative this time: there was a notable absence of grandstanding, no pledge of lives, fortunes, and sacred honor. The substance was more conservative as well: no insistence on popular control, as was evidenced in the Pennsylvania Constitution of 1776. Instead, government was placed at arm’s distance from the people, with only one-half of one of the three branches under their direct control. The "framers," as we call them, faced an abundance of troublesome issues, several of which we study at length: the power of large states versus small states, for instance, and what to do about slavery. Despite their differences, however, all delegates shared an overarching goal: to create a powerful and efficient central government, but not so powerful as to invite or enable tyranny.

On September 17, when all was said and done, the framers opened the chamber doors. One large hurdle remained: the Constitution they created had to be sold to the people. At this late point in the game, when no additional input would be accepted, the nation embarked on its second grand debate. The issue was simply whether to accept or reject the plan, a take-it or leave-it proposition. "We, the people" were asked to approve the new form of government, but the "people" did not drive the process forward, as they had done eleven years earlier.

Taking an overview of the two acts of nation-creating that transpired in Independence Hall, and calling forth as well the events in lesser-known venues, we see history at work in very different ways. Then, as now, power traveled both up and down social and political hierarchies. It flowed from inside chambers to the population at large and from the people outside to the men within. Sometimes the so-called leaders led, as we commonly assume, but at other times they received their directives from the people and had little choice but to follow. Our two most sacred documents demonstrate these opposite trajectories in the political process. The Declaration of Independence resulted from an immense outpouring of popular sentiment, with commoners driving their representatives forward. The Constitution, on the other hand, was conceived in secret behind closed doors, and then marketed to those outside.

To this day, we are trying to work out the ambiguous implications of these dissimilar events, which have come to signify both the city and the nation.

Ray Raphael is an independent scholar who has written Founding Myths: Stories That Hide Our Patriotic Past (2006), A People’s History of the American Revolution: How Common People Shaped the Fight for Independence (2001), and The First American Revolution: Before Lexington and Concord (2003).