Yellow Fever 1793

by Richard Brookhiser

Late in August 1793 Philadelphia was struck by a strange and virulent disease. Patients developed aches, chills, and fever, vomited black bile, and turned yellow. Some recovered, but many died. The yellow fever, as it was called, had visited Philadelphia before but not for thirty years. Its toll now was ghastly. In normal times two to five Philadelphians were buried every day. But by the end of August the daily figure regularly passed twenty; by the second week of September it exceeded forty.

Late in August 1793 Philadelphia was struck by a strange and virulent disease. Patients developed aches, chills, and fever, vomited black bile, and turned yellow. Some recovered, but many died. The yellow fever, as it was called, had visited Philadelphia before but not for thirty years. Its toll now was ghastly. In normal times two to five Philadelphians were buried every day. But by the end of August the daily figure regularly passed twenty; by the second week of September it exceeded forty.

Philadelphia was one of the most flourishing cities in the English-speaking world. Its metropolitan area counted fifty thousand people, and its merchants did business round the globe. The University of Pennsylvania, founded by Benjamin Franklin as the College of Philadelphia, had opened the first medical school in America, and the city’s doctors were numerous and capable. They disagreed however on how to treat the deadly disease. Benjamin Rush, one of the most eminent among them, prescribed bleeding and purging to rid the system of its invader. Other doctors tried to ease their patients through the crisis with bark (quinine), Madeira, and cold baths. Rush and his colleagues took their disputes to the newspapers. They also argued about the vectors of the disease: was it transmitted by infected air? If so, would firing cannons or muskets help clear the air? Or was it passed person to person, in which case quarantines were necessary?

A century later Cuban epidemiologist Carlos Finlay and US Army doctor Walter Reed proved that yellow fever is transmitted by the bites of infected mosquitos. In his 2013 book Ship of Death: A Voyage That Changed the Atlantic World, Billy G. Smith argues that the disease-bearing insects arrived in Philadelphia aboard a British ship, the Hankey, which sailed in 1792 to an island off the coast of Guinea to found a multiracial abolitionist settlement. This idealistic venture foundered, thanks to the attacks of hostile neighbors and yellow fever. The Hankey was then converted by the British navy into a troopship that called at Barbados, Grenada, Haiti, and Philadelphia before returning home, spreading yellow fever in its wake.

As summer turned to fall, the death toll rose. At the end of September the daily burial rate averaged almost seventy. By mid-October it had soared past one hundred. J. H. Powell, the twentieth-century chronicler of the epidemic, waxes grimly eloquent: “This was the height of the plague, the height of demoralization, of despair, the height of disaster. The city was no human thing at all, but a place of quivering stench and filth, a place ruled by unreason.”[1]

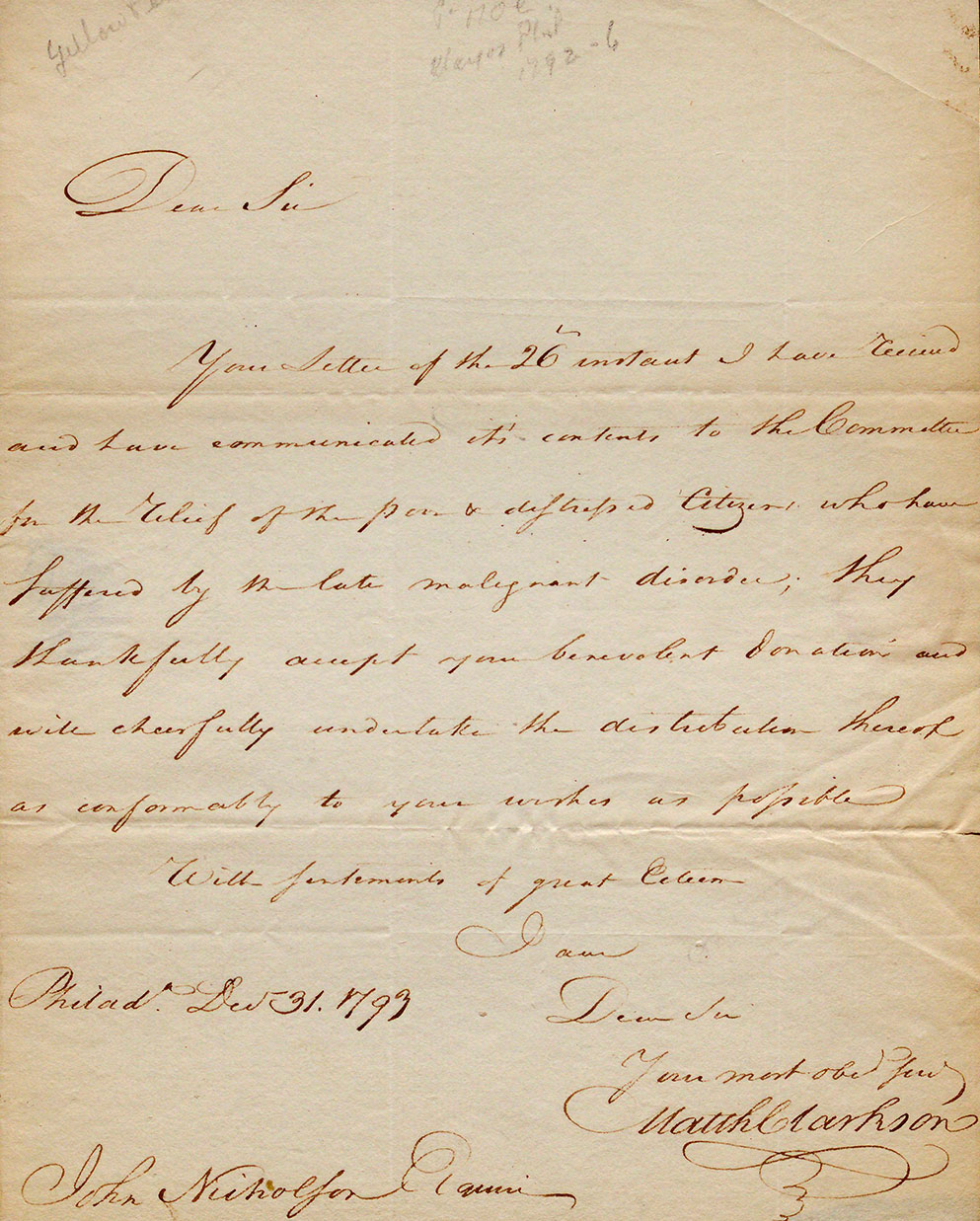

Everyone who could leave did. Regular civil government ceased to function. Powell again: “Councilmen left, and aldermen, judges and magistrates . . . The twenty-three night watchmen supposed to be on duty every night dwindled to a handful.”[2] Matthew Clarkson, the mayor, stayed at his post, running the stricken city with the help of volunteers. Together they made an odd lot. Clarkson, a conservative Federalist, was a wealthy underwriter. Others were artisans or shopkeepers. Jean Devèze, a French doctor, was an immigrant from Haiti. Richard Allen and Absalom Jones were former slaves who had bought their freedom as young men and founded two Black churches, pastored by themselves (Allen’s was Methodist, Jones’s Episcopalian), as well as a Free African Society to aid Black people in need. Now they enlisted their fellow African Americans to come to the aid of the needy community.

Clarkson and his team commandeered Bush Hill, a vacant mansion on an elevated site, and turned it into a hospital devoted to yellow fever patients. They organized carriers to fetch the sick from their homes or from the streets where they had collapsed, nurses and doctors to tend to them, and gravediggers to bury them. The last were busy. Dr. Devèze and the other physicians at Bush Hill had no miracle cures. But the ad hoc hospital was clean and orderly, and the sufferers were treated humanely.

The Bush Hill experience proved a negative. If yellow fever was passed from person to person, why did only three of its doctors and nurses, who were in constant contact with the sick and the dying, catch it? (Two of the three died.)

The city’s African American angels of mercy were attacked for their pains. Mathew Carey, a publisher and one of Clarkson’s volunteers, wrote a pamphlet on the epidemic, A Short Account of the Malignant Fever, which went through four editions and was translated into French, Dutch, German, and Italian. Although Carey praised Allen and Jones, he accused members of the Free African Society who did much of the heavy lifting—carrying patients, burying the dead—of profiteering. Carey was repeating a mistaken rumor: frantic relatives of the sick and dying offered huge sums for moving or disposing of them, which made the workers who did so seem extortionate. Allen and Jones wrote a dignified reproof, A Narrative of the Proceedings of the Black People, During the Late Awful Calamity in Philadelphia, in which they testified that the city’s Black residents showed “more humanity, more real sensibility” than many of their neighbors.[3]

Yellow fever darkened the counsels of the federal government. Philadelphia had been the nation’s capital since 1790. Congress had adjourned in March; senior members of the executive branch had stayed on to deal with the aggressive antics of the French diplomat Citizen Genêt, but had decamped as the epidemic took hold. But Congress was scheduled to meet again in December. What if the capital continued to be unlivable? Did President George Washington have the authority to summon Congress to convene elsewhere? He explored this constitutional question with his favorite young advisors, Rep. James Madison and Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton, both like him veterans of the Constitutional Convention. Unhappily, they disagreed. Madison said that Congress’s location was fixed by law, and only Congress could change it. Not so, said Hamilton; emergencies required emergency measures. Suppose the capital had been occupied by invaders, or swallowed in an earthquake?

Washington decided to lodge at an inn in Germantown, then a suburb, in late October and watch developments. On November 10 he rode into the city proper to see for himself. Over the previous three weeks the daily burial rate had plunged to the twenties. Philadelphia looked healthy to him. He judged that Congress could return as planned, and that there would be no constitutional quandary.

The cause, unbeknownst to anyone, was that cool weather—the first frost had fallen on October 28—was killing the mosquitos. Philadelphia’s fever had broken.

But the cost was tremendous. Mathew Carey’s Short Account listed 4,044 dead. The real toll was probably closer to five thousand.

Philadelphia revived almost instantly; it would be the second largest city in the United States, after New York, until the end of the next century, when Chicago bumped it to third.

In 1799 Richard Allen would deliver a eulogy for George Washington, praising him for freeing his slaves in his will: “he dared to do his duty, and wipe off the only stain with which man could ever reproach him.”[4]

An unusual twist of fate awaited Matthew Clarkson. In 1804 he was living in New York when fellow Federalist Alexander Hamilton was killed in his duel with Aaron Burr. Gouverneur Morris described in his diary meeting Clarkson a few days later. His face was bathed in tears. If we were brave, he said, we would defy challenges to duels. “But we are all cowards.”[5]

No one in America had a better title to bravery than Matthew Clarkson. But some wicked social customs—dueling, slavery—were more potent than plagues.

Richard Brookhiser is senior editor of the National Review, an award-winning historian, and the recipient of a National Humanities Medal. His recent books include Give Me Liberty: A History of America’s Exceptional Idea (2019), John Marshall: The Man Who Made the Supreme Court (2018), and Founders’ Son: A Life of Abraham Lincoln (2014), which was a finalist for the 2015 Gilder Lehrman Lincoln Prize.

[1] J. H. Powell, Bring Out Your Dead: The Great Plague of Yellow Fever in Philadelphia in 1793 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1949), p. 247.

[2] Powell, Bring Out Your Dead, p. 55.

[3] Absalom Jones and Richard Allen, A Narrative of the Proceedings of the Black People, During the Late Awful Calamity in Philadelphia, in the Year 1793: And a Refutation of Some Censures, Thrown Upon Them in Some Late Publications (Philadelphia, 1794), p. 9. Read excerpts from the Narrative in our Spotlight on a Primary Source: Black Volunteers in the Nation’s First Epidemic, 1793.

[4] Richard Allen, Eulogy for George Washington delivered to the congregation of Philadelphia’s African Methodist Episcopal Church on December 29, 1799, printed in the Philadelphia Gazette, December 31, 1799, p. 2.

[5] Matthew Clarkson quoted by Gouverneur Morris in 1804, The Diary and Letters of Gouverneur Morris, Vol II, ed. Anne Cary Morris (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1888), p. 458.