Women and the Home Front: New Civil War Scholarship

by Catherine Clinton

In the 1960s the image of Scarlett O’Hara standing before a Technicolor-drenched panorama from Gone With the Wind (1939) was still firmly planted within the imagination of the American public as a symbol of women on the Civil War home front. More than half a century later, O’Hara retains her crown as an iconic afterimage of the Lost Cause, but there is a new cast of female characters crowding into revised portraits—with black women as likely as white to take center stage. The fictional rebel starlet O’Hara has had her close-up long enough, and must make room for more realistic, less romanticized visions of Civil War–era women. As Drew Faust points out in Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War, women held a central role in mourning losses that befell both armies—demonstrating both the insurmountable gulf and the tight connections between home front and battlefield.

In the 1960s the image of Scarlett O’Hara standing before a Technicolor-drenched panorama from Gone With the Wind (1939) was still firmly planted within the imagination of the American public as a symbol of women on the Civil War home front. More than half a century later, O’Hara retains her crown as an iconic afterimage of the Lost Cause, but there is a new cast of female characters crowding into revised portraits—with black women as likely as white to take center stage. The fictional rebel starlet O’Hara has had her close-up long enough, and must make room for more realistic, less romanticized visions of Civil War–era women. As Drew Faust points out in Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War, women held a central role in mourning losses that befell both armies—demonstrating both the insurmountable gulf and the tight connections between home front and battlefield.

Novelists in the past half-century have given us Civil War survivors like Sethe (in Toni Morrison’s Beloved), as well as Ada Monroe and Ruby Thewes (in Charles Frazier’s Cold Mountain). Louisa May Alcott imparted valuable lessons in her Little Women, which like her Hospital Sketches, bears rereading. Equally compelling, the voices of women newly discovered in dusty archives present collective experiences that broaden and deepen our appreciation of women’s indelible influence on all society, but especially countries at war. Historians have generated a diverse and splendid range of wartime women to contemplate.

When Mary Elizabeth Massey published her commissioned study for the Civil War centennial, Bonnet Brigades: American Women and the Civil War (1966), she had few monographs to draw upon. But American women’s history has since created a tidal wave of work, alongside revised interpretations of slavery, emancipation, and the African American experience. This wave of new scholarship has coincided with a digital revolution that gives us unprecedented access to documents and images from across the globe. Much of this "bottom up" analysis of "beamed up" resources highlights opportunities to include women, particularly black women, neglected in previous commemorative eras. Today, on the cusp of the Civil War’s sesquicentennial, we can recover with a few clicks on our computers the voices of girls like Carrie Berry, whose written account of her tenth birthday in August 1864 reveals much about white families during federal invasion (http://www.americancivilwar.com/women/carrie_berry.html).

In addition to Berry’s account, we can locate the story and the newly erected statue of Elizabeth Thorne, the pregnant wife of a soldier gone to war who buried Union soldiers during the summer of 1863, following the Battle of Gettysburg in her hometown, when the dead and wounded left behind outnumbered the living ten to one. We might find out about the lives of those like the African American woman standing in the doorway of Winslow Homer’s 1866 painting, Near Andersonville, from the Library of Congress online archive, Born in Slavery: http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/snhtml/snhome.html.

Since the beginning of this century, educators have been inundated with newly published Civil War manuscripts, letters, and diaries making readily available resources addressing previously neglected aspects of war. All of this alongside new interpretations and perspectives renews our appreciation of women’s multiple roles in the conflict.

One of the most famous women to emerge from Ken Burns’s The Civil War (1990) was Mrs. Sullivan Ballou, the "very dear Sarah" who lost her husband, who died at the Battle of Bull Run at the age of thirty-two. Burns uses the motif of Ballou’s letter to highlight men’s sacrifice (and unfortunately left too much of the story of women’s sacrifices on the cutting room floor). But the image of loyal women at the Yankee hearthside—cue Marmee March and her daughters from Little Women—remains imprinted before, during, and after "the Burns effect." Thanks to recent studies by Judith Giesberg (Army at Home) and Nina Silber (Gender and the Sectional Conflict), Northern women who struggled for Union victory are emerging from the shadows. We know now of nurses Katharine Wormeley and Cornelia Hancock—not just Clara Barton. Where once we only heard about Harriet Beecher Stowe we know writers and reformers like Josephine Shaw Lowell and America’s "Joan of Arc," Anna Dickinson. There are now studies of several of the women who served as spies—Rose Greenhow and Elizabeth Van Lew—as well as women who served as soldiers, Sarah Emma Edmonds and Sarah Rosetta Wakeman (who died as Pvt. Lyon Wakeman). And beyond these "impermissible patriots," the ordinary and everyday experiences of wartime women are also in the limelight.

Over the past two decades, I have co-edited two works that capture some of the women previously left in the background: Divided Houses: Gender and the Civil War and Battle Scars: Gender, Sexuality and the American Civil War. Historians are bringing to the fore a wide range of Civil War women including authors, agitators, nuns, prostitutes, divorcing wives, grieving widows, and plantation mistresses. The grit, muscle, and spark of this avalanche of new work make me even more hopeful about the next crop of scholarship scheduled for the upcoming sesquicentennial.

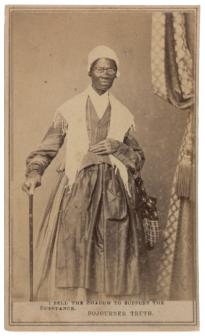

Most significantly, there are exponential gains in information about the lives of those most dramatically changed by wartime: ex-slaves. Women like Sojourner Truth and Harriet Tubman have been accorded new biographies in the past few years, which afford new insights into their Civil War contributions: Truth giving stump speeches to re-elect Lincoln and Tubman as a heroic leader of the Combahee River raid. In just one night in July 1863, Tubman smuggled more than 700 runaway slaves to safety and freedom in wartime Carolina.

In addition, recent biographies of African American pathbreakers like Harriet Jacobs and Elizabeth Keckly deepen our understanding of the war’s layered meanings for "freed" black women. Jacobs was the first self-emancipated woman to publish a slave narrative. Along with her daughter, she undertook war work to raise funds for her fellow ex-slaves. Elizabeth Keckly, a former slave who had saved to buy her own freedom and that of her child before migrating to Washington, was a valued employee of the Lincoln White House. She began as a dressmaker but became a confidante for the First Lady, Mary Lincoln, especially following the death of the Lincolns’ son Willie. Keckly lost her only son in the Battle of Wilson’s Creek in August 1861, and this loss drew the women together.

Also in time for the sesquicentennial, a new version of Mary Chesnut’s diary—one of the most cited Civil War memoirs—will be published by Penguin Classics. She wrote early in the war: "We try our soldiers to see if they are hot enough before we enlist them. If, when water is thrown on them, they do not sizz, they won’t do. Their patriotism is too cool." (Penguin edition, p. 68.) Her tart observations have provided keen insight for readers over the past century, and fodder for conflicting interpretations for each rising generation of Civil War scholars. The reminiscences of Susie King Taylor, the only black woman to leave a record of her time with the Union Army, and Jean Fagan Yellin’s two-volume set of Harriet Jacobs’s family papers broaden our appreciation of war’s impact on individual black women, while Thavolia Glymph’s study, Out of the House of Bondage, attempts the larger story of enslaved women’s struggles for freedom.

While hundreds of black and poor white women are finally gaining recognition as powerful actors in the drama of war through monographs and websites, Civil War women provide a thriving biographical industry, including recent studies of first ladies such as Joan Cashin’s look at Varina Davis (First Lady of the Confederacy) and my own take on Mary Lincoln (Mrs. Lincoln: A Life). Each of these occupants of their respective White Houses suffered barbs from the press and were subjected to severe criticisms during their husbands’ White House tenures. The persecution of Mary Lincoln outlasted Mrs. Davis’s ordeal, and her controversial reputation continues into contemporary times. Along with these prominent female figures, ethnic and immigrant women, and the working class and poor have made it into the chronicle of war, alongside vivandieres with the troops, women employed by the Treasury department, girls blown up in munitions’ factories, matrons in hospitals, teachers in the sea islands, and laundresses in the camps—not to mention the obligatory camp followers.

Most significantly, it is Confederate women—the stepdaughters of that tired image of Scarlett O’Hara—who have gotten the lion’s share of attention, with studies by Stephanie McCurry, Laura Edwards, George Rable, Edward Campbell and Suzanne Lebsock, and LeeAnn Whites, to name just a few writers and scholars shedding light on the subject. My study Tara Revisited: Women, War and the Plantation Legend includes more than a hundred images, including daguerreotypes and stereoscopic views as counterpoint to the myth of the Confederate woman perpetuated in "remembrance of things imagined." In reality, commemoration preoccupied many women in post–Civil War America, and it was raised into an art form by white Southern women. The United Daughters of the Confederacy and other white Southern memorial groups launched cults of memory that dominated popular cultural assessments of the war’s impact for nearly a century. Some scholars have suggested Confederate women’s loss of will may have contributed to the defeat of Southern secessionists. The study of women in historical motivation shifts our perceptions of the past and our templates for the future.

As more scholarship emerges on the Civil War home front, a variety of dissenting perspectives accompanies it, especially in terms of Southern Unionists. These portraits have become more sharply sketched in recent years. From Phillip Paludan’s magisterial Victims (a study of the January 1863 murder of thirteen boys and men in western North Carolina), to my own Southern Families at War (Confederate Jews and Texan Germans, to name but two groups covered), to Alecia Long and LeeAnn Whites’s study of women in the occupied South (Occupied Women)—all provide an even more diverse appreciation of home front politics and culture. Thankfully, creativity and complexity are the hallmarks of a new age of Civil War scholarship as we approach 2011.

Catherine Clinton is a professor of history at Queen’s University Belfast. She specializes in American history, with an emphasis on the history of the South. Her recent books include Harriet Tubman: The Road to Freedom (2004) and Mrs. Lincoln: A Life (2009).