"Was Woman True?" Sojourner Truth and the 1867 American Equal Rights Association Anniversary Meeting

by Margaret Washington

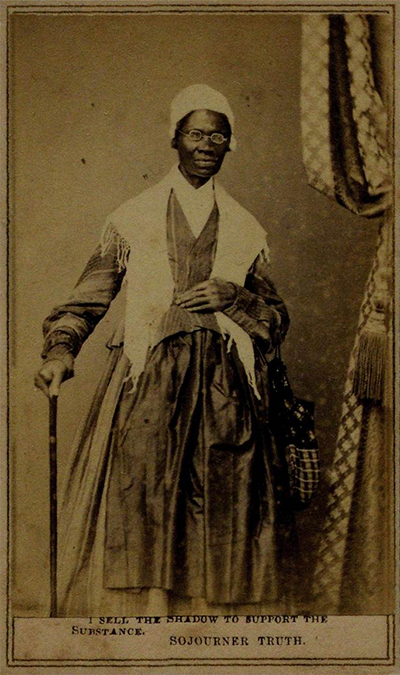

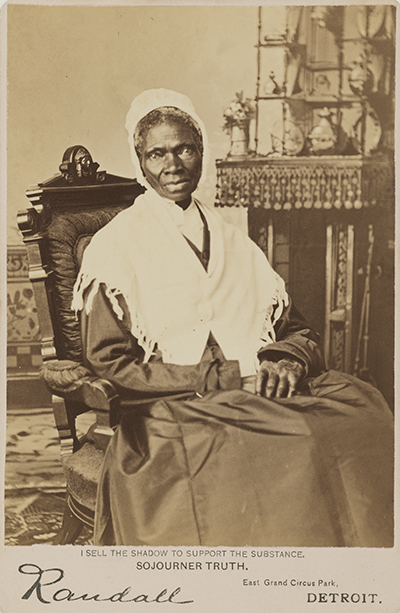

“I suppose,” said Sojourner Truth in 1867, “I am about the only colored woman that goes about to speak for the rights of the colored woman.”[1]

“I suppose,” said Sojourner Truth in 1867, “I am about the only colored woman that goes about to speak for the rights of the colored woman.”[1]

By then, a few other African American women had joined her. But none rivaled Sojourner’s outspoken wisdom, wit, consistency, and visibility. She was the only Black woman speaker at the first National Woman’s Rights Convention in 1850, and was already known for advocating antislavery, women’s rights, and other reforms.

Sojourner Truth was born enslaved in 1797 in New York’s mid-Hudson Valley, then a Dutch-speaking region. As a young woman, she “took” her freedom because her master broke his promise to free her; then she successfully regained her five-year-old son, illegally sold into southern slavery. Despite not learning English until adulthood, Sojourner was a popular Methodist preacher before becoming an archetypical representative of positive change in America. Overcoming crucibles of enslavement, racism, misogyny, poverty, and lack of education, Sojourner’s exploits, said her associate Parker Pillsbury, could fill a library.[2] Above all, she sought equality for African Americans, and for women.

After a lengthy illness during the Civil War, in 1863 Sojourner left her Michigan home and traveled to Washington, DC to see the freedom of her people. There she met President Abraham Lincoln who urged her to be a counselor at Freedman’s Village. She also worked as a nurse at Freedman’s Hospital. Observing thousands of destitute freed people from Virginia and Maryland crowded into the District of Columbia, Sojourner used her Northern contacts to secure employment for Black families willing to relocate. Meanwhile, her woman’s rights co-workers also sought her assistance.

In January 1866, Susan B. Anthony wrote to Sojourner Truth: “My dear friend, I know you will be glad to put your mark to the inclosed petition, and get a good many to join it, and send or take it to . . . Congress.”[3] The petition challenged Congress’s use of the word “male” in the proposed Fourteenth Amendment, which would ensure birthright citizenship.

Sojourner’s work in Washington kept her from two momentous annual meetings in 1866. The National Woman’s Rights Convention met for the first time since 1860, having agreed not to meet while the nation was at war. In 1866, the National Woman’s Rights Convention was transformed into the American Equal Rights Association (AERA). The American Anti-Slavery Society (AASS) also convened in 1866 and dedicated itself to Black suffrage. The membership of each of these organizations was almost identical. Speakers at the inaugural convention of the AERA included Frederick Douglass, who was elected a vice president; Frances Watkins Harper, a poet and novelist; Abby Kelley Foster, an abolitionist lecturer; and Wendell Phillips, the new AASS president. Both organizations went on record protesting the use of the word “male” in the proposed Fourteenth Amendment and supporting universal suffrage. Wendell Phillips’s interjection, that Black men’s “claim to this right might fairly be considered to have precedence,” spelled trouble ahead.[4] Yet in 1866, everyone campaigned for universal suffrage. Sojourner Truth accompanied a group of Washington, DC freed people to new homes and jobs in Monroe County, New York. While there, she spoke to a huge audience on behalf of universal suffrage.

In March 1867, Elizabeth Cady Stanton wrote, “Dear Sojourner, will you try and be present at our coming anniversary and help us bury the woman and the Negro in the citizen and make New York State a genuine republic?”[5]

Sojourner agreed to attend the AERA’s first anniversary meeting, held in New York City. She was Stanton’s houseguest. Having preached in the city for more than fifteen years, Sojourner Truth had a host of visitors. She was also interviewed by the New York World.

At the convention, which Douglass, Phillips, and Harper did not attend, Sojourner Truth was greeted with loud, sustained cheers. Thanking the audience, she then added, “I don’t know how you will feel when I get through. I come from another field—the country of the slave.” Slavery was partially destroyed but not entirely. “I want it root and branch destroyed. Then we will all be free indeed.” Moving on to women, Sojourner asserted that freed women needed rights as much as freed men. “There is a great stir about colored men getting their rights, but not a word about the colored women.” She believed that Black women and children suffered more than Black men. Black women went out and worked as washerwomen, “which is about as high as a colored woman get.” Observing that men, who had the upper hand, took the money earned by women who worked hard for little pay, Sojourner then exclaimed that men “then scold [them] because there is no food.” She applauded a new District of Columbia ruling granting Black male suffrage. But if Black women had suffrage, they could be more independent and keep their own money.

At the convention, which Douglass, Phillips, and Harper did not attend, Sojourner Truth was greeted with loud, sustained cheers. Thanking the audience, she then added, “I don’t know how you will feel when I get through. I come from another field—the country of the slave.” Slavery was partially destroyed but not entirely. “I want it root and branch destroyed. Then we will all be free indeed.” Moving on to women, Sojourner asserted that freed women needed rights as much as freed men. “There is a great stir about colored men getting their rights, but not a word about the colored women.” She believed that Black women and children suffered more than Black men. Black women went out and worked as washerwomen, “which is about as high as a colored woman get.” Observing that men, who had the upper hand, took the money earned by women who worked hard for little pay, Sojourner then exclaimed that men “then scold [them] because there is no food.” She applauded a new District of Columbia ruling granting Black male suffrage. But if Black women had suffrage, they could be more independent and keep their own money.

She went on in that manner, occasionally interjecting the humor for which she was famous. Nonetheless, Sojourner was serious.[6]

However hard it was for Black men to hear, Sojourner echoed what Frances Watkins Harper had observed in the South Carolina Sea Islands. Gullah-Geechee women’s complaints of infidelity, physical abuse, and desertion prompted Harper to preach against “men ill-treating their wives.”[7] Harper recalled a work song women sang while picking cotton: “Black men beat me/ White men cheat me/ Won’ get my hundud (hundred pounds of cotton) all day.”[8]

Fireworks erupted the next day when Black restauranteur George Downing argued with Lucretia Mott and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who insisted that women and Blacks obtain suffrage together. Downing agreed, but asked if they would they oppose Black male franchise if it did not include women. Mott was silent. Stanton insisted Black men were too “degraded” and “oppressed” to be trusted with these rights and “would be . . . despotic.” Blacks and women must “go into the kingdom [of politics] together.” Stanton also used Sojourner’s talking point about Black men oppressing Black women. Black abolitionist Charles Remond agreed with them. Abby Kelley Foster objected: “Are we not dead to the sentiment of humanity?” Black men were still treated like slaves. Downing proposed a resolution: regretting that the “right sentiment” did not exist for giving women the ballot, but “rejoicing” that sentiment favors “enfranchisement of the colored man.”[9] The motion was defeated.

Sojourner, who often combined politics and scripture, was at the podium again. Emphasizing male dominance, she suggested that the patriarchy was as bad as the slave power. Men had devils in them, she said, and they wanted everything. She delighted the audience by using the biblical parable of Jesus casting devils into swine. Sojourner had pondered why Jesus didn’t send the devils into sheep. Her rhetorical answer compared men to swine (selfish, fickle, unclean, and greedy), and women to sheep (humble, forbearing, generous, patient, and obedient). Eventually, the devils inside the swine drove them into the sea, thus implying, suggesting, or proposing man’s fate. Recalling the Crucifixion, she explored women’s spirituality, loyalty, and love. Women went to the tomb, found Jesus gone, believed he had risen, rejoiced, and went to tell his doubting followers. “Was woman true?” Sojourner queried her audience. “That was the faithfulness of a woman. You cannot find such any faith of man like that, go where you will.”[10]

Following Sojourner’s biracial solidarity effort came Stanton’s derision of Black men. Why should a wealthy woman be denied the vote in New York when a Black man could vote for $250.00, she demanded. It was time, she said, to save the republic from degraded manhood: “The time for doing justice to the negro is past.”[11] Charles Remond who previously supported Stanton, was now on his feet. Black men carried the musket in the war, he proclaimed; women did not have the same urgency for suffrage as Black men. Sparks flew for a while, but both Stanton and Remond calmed down and insisted the answer was universal suffrage.

Sojourner Truth, as Stanton’s houseguest, was in a difficult position. Stanton came dangerously close to destroying amiable biracial friendships. Asked to speak again, Sojourner acknowledged that some women had spoken passionately. But “there was nobody gettin’ mad, or if they was,” she said amid laughter, “they didn’t let us know it.” Although she wasn’t exactly accurate, Sojourner realized the importance of such efforts. Understanding both sides’ earnestness, Sojourner also personified the complexities of suffrage beyond race. Having purchased property with proceeds from sales of her Narrative, she wanted to “go up to the polls”; as a property owner, she had a right. “Every year I got a tax to pay. . . . Road tax, school tax, and all these things.” Yet she could not vote. Concluding her final appearance with a song, vowing she would vote before she left the world, Sojourner also paid her AERA membership dues.[12]

For freed people, conditions in the South deteriorated daily. But Stanton and Anthony ratcheted up their anti-Black male suffrage activities, and they campaigned against the Fifteenth Amendment. Sojourner did the opposite. She campaigned throughout western New York for Black male suffrage.

Sojourner Truth was in Washington in 1870 when Secretary of State Hamilton Fish of New York declared the Fifteenth Amendment ratified. Now, pledging to devote more time to woman’s suffrage, Sojourner headed to New York for the Woman’s Suffrage Meeting. On May 4, 1870, Elizabeth Cady Stanton wrote, “I hope, dear Sojourner, that you will be enfranchised before you leave us for the better land.”[13] Neither suffragist lived to see that day. But it did come.

Margaret Washington is the Marie Underhill Noll Professor of American History, Emeritus, at Cornell University. Her publications include Sojourner Truth’s America (University of Illinois Press, 2009) and A Peculiar People: Slave Religion and Community-Culture among the Gullahs (New York University Press, 1988).

[1] Sojourner Truth, quoted in Proceedings of the First Anniversary of the American Equal Rights Association, Held at the Church of the Puritans, New York, May 9 and 10, 1867 (New York: Robert J. Johnston, 1867), p. 20.

[2] Parker Pillsbury, The Acts of the Anti-Slavery Apostles (Concord, NH, 1883), p. 137.

[3] Susan B. Anthony to Sojourner Truth, January 13, 1866, printed in Sojourner Truth, Olive Gilbert, and Frances W. Titus, Narrative of Sojourner Truth; A Bondswoman of Olden Time (Boston, 1875), p. 282.

[4] Wendell Phillips, quoted in the National Anti-Slavery Standard, June 9, 1866, printed in Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, and Matilda Joslyn Gage, eds., History of Woman Suffrage, vol. 2: 1861–1876 (New York: Fowler & Wells, 1882), p. 7.

[5] Elizabeth Cady Stanton to Sojourner Truth, March 24, 1867, Amy and Isaac Post Family Papers, Rush Rees Library, University of Rochester.

[6] Sojourner Truth, Address to the First Annual Meeting of the American Equal Rights Association, New York City, May 9, 1867, quoted in Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, and Matilda Joslyn Gage, eds., History of Woman Suffrage, vol. 2: 1861–1876 (New York: Fowler & Wells, 1882), p. 193.

[7] Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, December 29, 1870, quoted in William Still, The Underground Rail Road: A Record of Facts, Authentic Narratives, Letters, &c. (Philadelphia: Porter & Coates, 1872), p. 773.

[8] See Margaret Washington, Sojourner Truth’s America (University of Illinois Press, 2009), p. 338.

[9] Elizabeth Cady Stanton, May 10, 1867, quoted in Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, and Matilda Joslyn Gage, eds., History of Woman Suffrage, vol. 2: 1861–1876 (New York: Fowler & Wells, 1882), pp. 214, 216, and 215.

[10] Sojourner Truth, First Annual Meeting of the American Equal Rights Association (Second Speech), first published in the National Anti-Slavery Standard (June 1, 1867), p. 3; reprinted in Manning Marable, ed., Freedom on My Mind: The Columbia Documentary History of the African American Experience (New York: Columbia University Press, 2003), p. 7.

[11] Elizabeth Cady Stanton, quoted in Margaret Washington, Sojourner Truth’s America (University of Illinois Press, 2009), p. 340.

[12] Sojourner Truth, quoted in Proceedings of the First Anniversary of the American Equal Rights Association, Held at the Church of the Puritans, New York, May 9 and 10, 1867 (New York: Robert J. Johnston, 1867), p. 67.

[13] Elizabeth Cady Stanton, quoted in Margaret Washington, Sojourner Truth’s America (University of Illinois Press, 2009), p. 353.