Access this essay as a PDF, including key vocabulary terms and discussion questions, or read the text of the essay below.

The concept of “democracy” changed throughout early American history. In colonial times and in the early republic, the idea that average citizens could vote for leaders was relatively new. Having just broken away from the monarchy of Great Britain, the framers of the US Constitution were worried about the government having too much power. This concern impacted how the Constitution was written. For example, Article I of the Constitution gives state legislatures control over federal (national) elections, if Congress fails to set electoral standards. This decision has had long-lasting effects, still at play today, on who has access to the vote.

Voting rights in the new United States were very limited. Typically, only adult White male citizens could vote. Voters also had to own property, generally in the form of real estate and land. The Jacksonian era of the mid-1820s, 1830s, and early 1840s coincided with westward expansion. Many of the White Americans heading west owned no land. Moving west was their chance at land ownership and by extension, suffrage, or the right to vote. Suffrage became a rallying cry for less affluent men in their quest for citizenship and freedom. In new territories, they pushed for statehood as soon as possible so that their votes would also count in US federal elections.

During the Jacksonian era, nearly every free state in the North and Midwest extended voting rights to all White men, regardless of whether they owned property. In the South and Southwest, various voting restrictions remained for White men, because enslavers wanted to limit suffrage to men who would support the institution of slavery. In addition to property ownership requirements, voters had to pay a high fee in cash—a poll tax—to vote each year, and enslavers used intimidation, outright fraud, and various other forms of voter suppression. For example, during the 1860 presidential election, many southern states refused to allow men to cast ballots for Abraham Lincoln.[1]

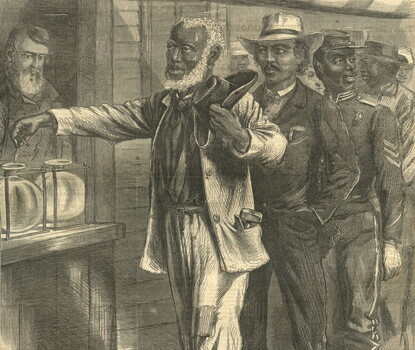

Voting was far from a “right” for most Americans during the antebellum, or pre-Civil War, period of US history. By the 1850s, a growing group of wealthy southern White men, usually born into slaveholding families of great privilege, began identifying themselves as aristocrats or oligarchs (members of a ruling class reserved for the few). This went against the concept of pure democracy and was more in line with the monarchy the US had broken from when separating from Great Britain. Many wealthy White southerners wanted a system based on hereditary privilege, caste, and rule by the elite few, and they would fight for that system, preying on racist fears, for the remainder of the nineteenth century. As Frederick Douglass wrote in 1888, “I am a good deal disturbed just now by the clamour raised for the disfranchisement of the colored voters of the South. The cry about negro supremacy is like the old cry . . . so often heard in the old time about the negroes going to cut their masters’ throats. It’s all humbug—There is nothing in it.”[2]

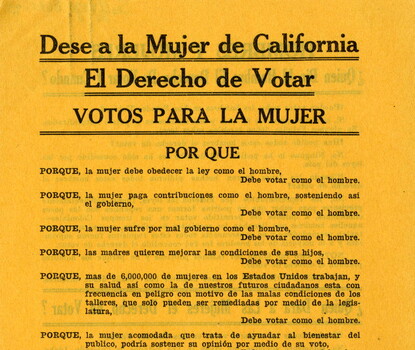

The fight for women’s suffrage in the United States gained momentum during the Jacksonian period as well. It grew in popularity alongside reform movements such as abolitionism and temperance. The antebellum-era women’s suffrage movement culminated in the Seneca Falls Convention of 1848, which was led by Lucretia Mott and other women’s rights activists. Taking the Declaration of Independence as her inspiration, Elizabeth Cady Stanton drafted the “Declaration of Sentiments,” a women’s rights manifesto that was signed by approximately 100 of the convention’s attendees. Of the many proposals in the Declaration of Sentiments, “elective franchise”—the right for women to vote—was unquestionably the most revolutionary.[3]

Still, it would not be until after the bloodiest episode in our nation’s history, the Civil War, that Black men would win voting rights through the Fifteenth Amendment (1870), and White women through the Nineteenth Amendment (1920). Nineteenth-century America had a long way to go with voting rights to approach anything close to what we think of as democracy today.

Keri Leigh Merritt works as a historian and writer in Atlanta, Georgia. She earned her BA from Emory University and her MA and PhD from the University of Georgia. Her first book, Masterless Men: Poor Whites and Slavery in the Antebellum South (Cambridge University Press, 2017), won both the Bennett Wall Award from the Southern Historical Association, honoring the best book in southern economic or business history published in the previous two years, as well as the President’s Book Award from the Social Science History Association.

[1] Bernard Mandel, Labor, Free and Slave: Workingmen and the Anti-Slavery Movement in the United States (1955; repr. Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2007).

[2] “Frederick Douglass on the disfranchisement of Black voters, 1888,” The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, https://www.gilderlehrman.org/history-resources/spotlight-primary-source/frederick-douglass-disfranchisement-black-voters-1888.

[3] Report of the Woman’s Rights Convention, Held at Seneca Falls, N.Y., July 19th and 20th, 1848. Rochester: Printed by John Dick, at the North Star Office, 1848. Report of the Woman’s Rights Convention - Women’s Rights National Historical Park (US National Park Service) (nps.gov).

Access the next essay in the series, "Pioneering New Methods to Expand Voting, 1865–1920."

Pioneering New Methods to Expand Voting, 1865–1920

by Prof. Lisa Tetrault (Carnegie Mellon University)

The Right to Vote Resource Suite

Essays

Read scholarly perspectives on the history of voting rights through essays geared to high school students

Lesson Plans

Learn how individuals and groups attempted to expand access to the vote in "Taking a Stand for Voting Rights: Six States, Six Stories, One Goal."

Digital Exhibitions

Explore our four-part digital exhibition on the history of voting rights, which includes audiovisual elements and interactive maps