"Show Them What an Indian Can Do": The Example of Jim Thorpe

by Joseph Bruchac

Although the twentieth century produced many great athletes, there is no one who stood out more than Jim Thorpe. That is not just my opinion. When Jim Thorpe won two gold medals at the 1912 Olympic Games, the king of Sweden said to him, “Sir, I believe you are the greatest athlete in the world.” (To which Jim responded, “Thanks, King.”) And, more than eight decades later, an ABC Sports poll named Jim as the greatest athlete of the twentieth century.

Although the twentieth century produced many great athletes, there is no one who stood out more than Jim Thorpe. That is not just my opinion. When Jim Thorpe won two gold medals at the 1912 Olympic Games, the king of Sweden said to him, “Sir, I believe you are the greatest athlete in the world.” (To which Jim responded, “Thanks, King.”) And, more than eight decades later, an ABC Sports poll named Jim as the greatest athlete of the twentieth century.

There were plenty of reasons for those writers to choose Jim Thorpe for that honor, even though it was more than half a century after his retirement from sports.

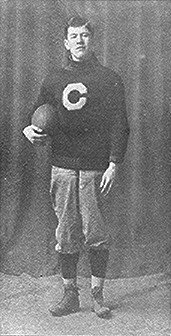

His dominance in track and field began while he was a student at the American Indian Industrial School in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. He and Lewis Tewanima, a Hopi man sent to Carlisle as a prisoner of war who was one of the greatest long-distance runners ever, were described as a “two-man team” by their coach, Pop Warner. They consistently won meets against major colleges with Jim taking first in one event after another. In fact, while at the Olympics, when asked what events he wanted to enter in addition to decathlon and pentathlon, Jim answered, “All of ’em.”

Jim was just as outstanding on the football field. At Carlisle he was a consensus All-American on a small team that beat all the powers of his time, including the Army in a legendary game. One of the Army’s star players in that game was none other than Dwight Eisenhower, the future World War II commander and thirty-fourth president of the United States. Eisenhower was knocked out of that game when he tried to tackle Jim Thorpe, and later described him as the toughest player he ever faced.

Jim was also such a talented baseball player that he was signed, with what was a huge bonus at the time, by the New York Giants in 1913. Although he played for several major league teams over the next six years and then continued playing lower division baseball for another decade, his greatest success as a pro player was in football.

Football was a sport just beginning to gain wide popularity. A dominant running back and a kicker, Jim joined the Canton Bulldogs at the same time he was in pro baseball, helping them win three championships as a player and coach. He coached and played in his own all-Indian team, the Oorang Indians, providing jobs for many of his former teammates from Carlisle. In 1920−1921 he was the first president of what would become the National Football League, using his fame to help the growth of the sport he loved.

He even barnstormed as a professional basketball player, traveling across the country with a team composed entirely of American Indians. It is recorded that Jim also excelled in lacrosse, bowling, archery, skating, pool, and almost any other sporting competition you could name.

His career as a professional athlete lasted until he was in his early forties, at the start of the Great Depression in 1929. Today he is enshrined in both the College Football Hall of Fame and the National Football Hall of Fame.

There is no doubt that all of those incredible accomplishments made Jim one of the most famous athletes of his time. He was well deserving of the honors his sports career earned him. However, Jim’s role as a true leader was not just in games he played and competitions he won. To understand his place in history you have to take into account the time in which he lived and the obstacles he had to overcome.

To begin with, Jim was born during a dark era in Native American history. His people, the Sac and Fox tribe, were then living in a tiny remnant of what had been their reservation. It was not even their original homeland. Like dozens of other tribes, they had been pushed west into the Indian Territory that was supposed to be Indigenous land forever. But “forever” only lasted until new federal laws opened over two million acres of the reservations to White settlers. The Oklahoma Land Rush began in 1889, two years after the birth of James Francis Thorpe in the town of Prague in Indian Territory.

As a whole, Native Americans were less than second-class citizens. In fact, citizenship was not extended to American Indians until 1924—eight years after Jim represented the United States in the Olympic Games. And even then many states prohibited Indians from voting until 1957.

The overall image of Native Americans then, and throughout much of the twentieth century, was a stereotyped one. They were seen as a vanishing people, one step removed from savagery. The popular image of the Indian was either as noble and doomed savage or as murdering redskin to be shot on sight.

When Jim’s father, Hiram, put his son on the train to go to school at Carlisle in far-off Pennsylvania, he spoke these words to him: “Show them what an Indian can do.”

Throughout Jim’s career, both as an amateur and a professional, he did just that, even though he often encountered prejudice. Newspaper accounts of Carlisle’s games demonstrate the racism of the time with such headlines as “INDIANS SCALP ARMY.” As a professional baseball player, he was unable to stay in the same hotels as his White teammates. There were signs in the windows in many states that read, “No Indians or Dogs Allowed.” People shouted insults at him when he was on the field. The color barrier Jim and a few other Native American ballplayers broke was a very real one.

There’s another way racial prejudice seems to have played a part in his story. Partway through his Carlisle years, he decided not to return to school. During that time he played semi-pro baseball in North Carolina for two summers. Then, in 1915, he was convinced to come back to Carlisle. Those were his two greatest years and included his wins at the Olympics. Then news stories came out about his playing semi-pro baseball for a few dollars a week. His gold medals were stripped from him because he was no longer an amateur. This probably would not have happened had Jim been a White athlete. Playing summer baseball in the Carolina League was something many White college athletes did—while keeping their amateur status. Long after Jim’s death, this injustice was recognized and his gold medals reinstated.

After his years in pro sports, Jim often had hard times, frequently short of money because of his generosity. He held various jobs, including years working in Hollywood. There he played bit parts and also represented other Native American actors, forming a casting company to pressure the studios into hiring real Native Americans. I have spoken to a number of those Native actors who have warm memories of Jim as a big-hearted friend, one who helped them get jobs and often represented them for free.

Jim was an advocate for his people. He made numerous trips to Washington, trying to convince the federal government to restore land holdings to the Sac and Fox nation.

In his last years, Jim traveled around the country giving lectures on three different topics: the story of his life, his views on contemporary sports, and issues affecting Native Americans, including their struggles to regain their lands.

His son Jack told me a story about his father. Jim had just finished giving a lecture and was paid twenty dollars. As he and Jack left the building, a man came up to them.

“Jim,” the man said, “I’m down and out. I don’t have money to eat. Can you help me?”

Jim immediately took out his wallet, handed the man that twenty and added another ten on top of it.

As they walked away, Jack said, “Pop, who was that man?”

“I don’t know,” Jim Thorpe replied.

“Why did you give him all of our money?”

“Because he said he needed it.”

Throughout his life Jim Thorpe not only showed what an Indian could do, but did it with a hand held out to others.

Joseph Bruchac is an Abenaki poet and scholar. Winner of the 1999 Lifetime Achievement Award from the Native Writers’ Circle of the Americas, he is the author of more than 120 books, including Jim Thorpe: Original All-American (SPEAK, published by the Penguin Group, 2006).