San Francisco and the Great Earthquake of 1906

by Robert W. Cherny

At the beginning of the twentieth century, San Francisco still reigned as the major seaport on the Pacific coast. The city traced its origins to 1776, when a Spanish expedition planted a mission and a military post at the end of the great peninsula between the Pacific Ocean and San Francisco Bay. An earlier Spanish expedition had discovered the bay in 1769 and quickly recognized it as one of the finest natural harbors in the world and potentially the most important harbor on the Pacific coast. In the 1830s and 1840s, the village of Yerba Buena grew up near a cove within the bay where seagoing ships could anchor and trade with local ranch owners and storekeepers. In 1846, during the war between the United States and Mexico, the US Navy took control of the bay end of Yerba Buena. One of the first acts of the naval officer in charge was to change the village’s name to San Francisco, so that it would be indelibly associated with the great bay.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, San Francisco still reigned as the major seaport on the Pacific coast. The city traced its origins to 1776, when a Spanish expedition planted a mission and a military post at the end of the great peninsula between the Pacific Ocean and San Francisco Bay. An earlier Spanish expedition had discovered the bay in 1769 and quickly recognized it as one of the finest natural harbors in the world and potentially the most important harbor on the Pacific coast. In the 1830s and 1840s, the village of Yerba Buena grew up near a cove within the bay where seagoing ships could anchor and trade with local ranch owners and storekeepers. In 1846, during the war between the United States and Mexico, the US Navy took control of the bay end of Yerba Buena. One of the first acts of the naval officer in charge was to change the village’s name to San Francisco, so that it would be indelibly associated with the great bay.

Soon after the name change, thousands of people were clamoring for passage to San Francisco—in 1848 gold was discovered in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada, inland from San Francisco. However, California remained remote from the eastern half of the nation, accessible only by difficult and dangerous routes. Most people chose to travel there by sea, either around the southern tip of South America or to Panama, over the isthmus by land transportation, then up the Pacific coast by ship.

San Francisco was on everyone’s lips, and the recently renamed village became the point of arrival for thousands of eager gold seekers. The village boomed, growing from 800 people in 1848 to 35,000 in 1852 and 57,000 in 1860, making it the fifteenth largest city in the nation. By 1880, San Francisco ranked seventh in size among the nation’s cities, and it remained among the ten largest cities through 1900.

From the Gold Rush onward, San Francisco was the metropolis of the West. It was by far the largest Pacific coast port at a time when ocean transportation was the dominant mode of travel for people and goods. Its banks dominated western finance. The most powerful western corporations had their headquarters in San Francisco. The city’s foundries and iron works produced locomotives, technologically advanced mining and agricultural equipment, and ships. By 1900, to be certain, San Francisco’s dominant role was beginning to be challenged by other western cities including Los Angeles, Portland, Seattle, and Salt Lake City, but San Francisco was still the largest port and the center of western commerce and finance.

Then, at 5:12 a.m. on April 18, 1906, the residents of San Francisco, and numerous other Californians for many miles north and south, were jolted awake by a monstrous earthquake. The earthquake set church bells ringing, knocked down chimneys, twisted city streets and streetcar tracks, and broke water lines, gas pipes, and electrical wires. Hundreds of miles away in Los Angeles, Oregon, and Nevada people felt the earth shake.

The earthquake was one of the largest in American history. Recent estimates put the magnitude of the earthquake at 7.7 to 7.9, as compared to older estimates of 8.3, on the Richter scale. The earthquake was caused when the San Andreas Fault suddenly shifted along a distance of 296 miles. The epicenter of the quake was a short distance out at sea, near the southwestern part of San Francisco. Geologists estimate that the fault moved as fast as 1.7 miles per second. "I could see it actually coming," a policeman in San Francisco said. "The whole street was undulating. It was as if the waves of the ocean were coming toward me."

The San Andreas Fault, the source of this disaster, lies ten miles or more deep, at the meeting point of two tectonic plates, the Pacific and the North American. (A tectonic plate is one part of the earth’s crust. There are seven major tectonic plates and many more minor ones. Earthquakes and sometimes volcanoes occur where these huge plates of rock rub up against each other.) Geologists describe the San Andreas Fault as right-lateral strike-slip, which means that the Pacific side of the fault is slowly moving horizontally northward, usually by an inch or two per year. At times, however, the fault may suddenly lurch as much as several feet. Such movements deep in the earth produce earthquakes—and such movements along the San Andreas Fault and its branches have produced most of the largest earthquakes in American history.

During the San Francisco earthquake in 1906, new buildings with steel frames held up quite well. Buildings of brick or other masonry construction, without steel or iron reinforcement, were most likely to be damaged. Some lost entire walls. Brick chimneys collapsed all over the city. The fire chief was killed when a chimney fell into his bedroom. The most dangerous parts of the city were areas that had once been lakes, creeks, marshes, or branches of the bay, and that had been filled in to create solid ground for construction. Such areas tend to liquefy in an earthquake. Structures on such fill land suffered the most. Some wood-frame buildings, especially on fill land, were knocked off their foundations, but most other wooden structures held up reasonably well.

Fires broke out almost immediately, fed by gas from broken gas lines. Broken water mains meant that most fire hydrants were useless. Among the first parts of the city to burn were the densely populated wooden buildings south of Market Street, home to many of the city’s working class. For the next three days, city residents struggled to contain what became a firestorm—the heat of the fire was so intense that it pulled air into the fire, generating significant winds. Jack London, the novelist, watched the fire from a boat in the bay and described the firestorm this way: "It was dead calm. Not a flicker of wind stirred. Yet from every side wind was pouring in upon the city. . . . The heated air rising made an enormous suck. Thus did the fire of itself build its own colossal chimney through the atmosphere. Day and night this dead calm continued, and yet, near to the flames, the wind was often half a gale, so mighty was the suck."

General Frederick Funston, commander of Army troops at the Presidio, directed soldiers to keep order and help fight the fires. Without water, firefighters and federal troops tried to build firebreaks by blasting buildings. Some firefighters pumped water from the bay to fight fires near the waterfront. In the Italian part of the city, residents used huge vats of wine to put out fires.

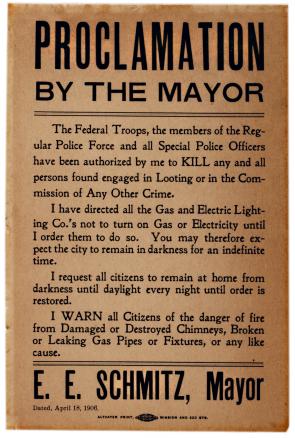

Rumors of widespread looting were mostly without basis, but those rumors led Mayor Eugene Schmitz to issue an order of doubtful constitutionality: "The Federal Troops, the members of the Regular Police Force, and all Special Police Officers have been authorized by me to KILL any and all persons found engaged in Looting or in the Commission of Any Other Crime." Some people were killed, either because they were looters or because they were mistaken for looters.

Because the fire burned for three days, many people had an opportunity to leave their homes as it became clear that the fires were moving in their direction. Some took ferry boats across the bay to Oakland or Berkeley. Others moved west, to neighborhoods not yet touched by fire or to Golden Gate Park. The refugees all carried what they could of their most prized possessions.

Earthquake, fire, and blasting destroyed the heart of the city—4.11 square miles and 28,188 buildings. More than half the city’s residents were homeless. Destruction was almost universal within the fire zone—new corporate headquarters as well as the shabby homes of the poor, churches and brothels, and a million books. The official record listed 498 deaths in San Francisco. Civic leaders, however, seem to have minimized the death count so as not to discourage future investment in the city. Recent research suggests that 3,000 or more died, either in San Francisco or in nearby areas. Total property damage, in 1906 dollars, was estimated at nearly $400 million, of which $80 million was due directly to the earthquake. One recent calculation suggests that reconstruction costs in today’s dollars would total $32 billion.

Donations poured in from individuals, organizations, and governments, some $9 million in all. Mayor Schmitz, suspected of corruption, appointed a special committee of fifty prominent citizens, led by former mayor James Phelan, to distribute the funds and plan relief and recovery. The Army set up twenty refugee camps, some on Army land and some in the city’s parks, which remained for a year or more. The Army and the city’s public health officials quickly restored sanitation and thereby averted a potential public health disaster.

San Francisco’s business leaders felt a special urgency to rebuild quickly—they feared that any delay would endanger their place as the financial and commercial center of the West. Business leaders and leaders of the construction unions, who had been warring for years, declared a truce. Some civic leaders urged a careful, planned approach to rebuilding that would include new boulevards, wider streets, and other civic amenities, but in the haste to rebuild few people were willing to wait for new street plans, and in the end the city was rebuilt with virtually the same street plan as before. Some civic leaders tried to use the devastation as an excuse to remove Chinatown from its location near the central business district, but they failed. The political fragmentation that prevented a planned approach to rebuilding also hindered reconstruction of public buildings—not until 1916 did the doors open on a new city hall.

San Francisco’s civic leaders wanted to demonstrate to the world that their city had arisen from the ashes. In 1909, with reconstruction still underway on every side, a mass meeting of the city’s business leaders launched the city’s bid to host a great international exposition to celebrate the opening of the Panama Canal. Called the Panama-Pacific International Exposition, the great fair opened in 1915, dominated by a dazzling "Tower of Jewels." Though the exposition presented vast exhibition halls that displayed the commercial and cultural products of much of the world, San Francisco civic leaders had a larger purpose—they wanted to demonstrate to the world that their city had completely recovered from the devastation of 1906.

The 1906 earthquake was important in other ways as well. Scientists who studied the earthquake of 1906 significantly improved their understanding of earthquakes. Careful examination of the effect of the earthquake on various types of buildings helped architects and engineers to improve technologies for resisting seismic stress, and the rebuilding of the city showed efforts to strengthen buildings against seismic stress. Throughout the burned district, a new auxiliary high-pressure water system for fighting fires was installed; the new system had with special hydrants, reservoirs, and cisterns, and water mains designed to withstand an earthquake. In addition, San Francisco voters approved construction of a huge dam across the Hetch Hetchy valley, high in the Sierra Nevada, to increase the city’s water supply.

San Francisco today is a different city in many ways from the city of 1906. Once the largest city in the West, San Francisco today ranks third in size in the state of California; once a major port and manufacturing center, San Francisco today is a center for finance, technology (especially bio-technology), tourism, and culture.

Scholars differ on whether San Franciscans have learned from the experience of 1906. Some suggest that San Franciscans are too complacent about the dangers of another monstrous earthquake, but others point to more stringent building standards, seismic strengthening of older buildings, and a significantly improved ability to fight fires. In 1989, an earthquake of 6.9 magnitude, centered about sixty miles south of San Francisco, did significant damage in some places. A few unreinforced masonry buildings collapsed or lost walls. A few buildings on fill land crumpled. In a few places, broken gas lines ignited fires, and broken water lines hindered fire-fighting. Across the bay in Oakland, a freeway collapsed, killing forty people. In 1989, unlike 1906, the damage was limited, the fires were quickly contained, and the total death toll, other than those killed in the freeway collapse, was twenty-three. In the wake of the 1989 earthquake, further efforts were made to strengthen buildings and other infrastructure. Only time will tell if these preparations are adequate preparation for the next "big one."

Robert W. Cherny is a professor of history at San Francisco State University. His books include California Women and Politics: From the Gold Rush to the Great Depression (2011) with co-editors Mary Ann Irwin and Ann Marie Wilson; American Labor and the Cold War: Unions, Politics, and Postwar Political Culture (2004) with co-editors William Issel and Keiran Taylor; and American Politics in the Gilded Age, 1868–1900 (1997).