"The Politics of the Future Are Social Politics": Progressivism in International Perspective

by Thomas Bender

The American Progressive movement was not simply a response to the domestic conditions produced by industrialization and urbanization. Instead, it was part of a global response to these developments during an era of unregulated capitalism that accelerated the movement of people, ideas, goods, and money. The significance can be assessed, in part, by the fact that direct foreign investment—the globalization of capital—constituted a higher percentage of all investments in the 1890s than in the 1990s. Born out of a period of great wealth and growing inequality, the Progressive era heralded a global acceptance of government’s responsibility for the health and welfare of individuals against corporate or moneyed interests.

The American Progressive movement was not simply a response to the domestic conditions produced by industrialization and urbanization. Instead, it was part of a global response to these developments during an era of unregulated capitalism that accelerated the movement of people, ideas, goods, and money. The significance can be assessed, in part, by the fact that direct foreign investment—the globalization of capital—constituted a higher percentage of all investments in the 1890s than in the 1990s. Born out of a period of great wealth and growing inequality, the Progressive era heralded a global acceptance of government’s responsibility for the health and welfare of individuals against corporate or moneyed interests.

In the 1920s, the progressive historian Charles Beard observed that "modern civilization . . . is industrial." He and other reformers in the industrial nations sought to develop adequate political and policy responses to the new kinds of insecurity that came with modernity: industrial accidents, unsafe food and drugs, old age, sickness, unemployment, inadequate housing. They were equally disturbed by the era’s dramatic increases in economic inequality, with highly visible extravagance at the top and misery at the bottom.

Progressive concerns about the growing inequality and unchecked industrial expansion were part of a worldwide "reaction against the unwanted consequences of the unregulated market." Or, as Jane Addams put it at the Progressive Party Convention that nominated Theodore Roosevelt for the presidency in 1912, "the New Party has become the American exponent of a world-wide movement toward juster social conditions, a movement which the United States, lagging behind other great nations, has been unaccountably slow to embody in political action."

Nineteenth-century liberalism—identified with the industrial success of Great Britain—rejected government interference with the free operation of the economy. Its proponents embraced an ideology known in America as "laissez faire." But across a global industrial landscape a new generation of leaders was emerging. They recognized that cities and industry required new ideas and new policies. The emerging "social question" meant that this nineteenth-century liberalism needed to become a social liberalism. Joseph Chamberlain, the Liberal mayor of Birmingham, England, declared in 1883 that "the politics of the future are social politics." In 1907, Jane Addams wrote that "a large body of people" had come to the conclusion that the "industrial system is in a state of profound disorder" and it is unlikely that "the pursuit of individual ethics will ever right it." In the same year, Winston Churchill declared "in some effective form or another" the issues of "wages and comfort—and insurance for sickness, unemployment, and old age" would define the politics of the future. And, as far away as Japan, Seki Hajime, the reform-oriented university economist who became mayor of Osaka, argued that modern society made people more interdependent. Nations must therefore think in terms of a "social economy," in which government played a role in regulating business and providing for the general welfare.

None of these new liberals was a socialist. In fact, they feared socialism and sought liberal reform as an alternative to revolution and socialism. New liberals recognized that government could not do everything, but it could moderate the social evils of unregulated capitalism.

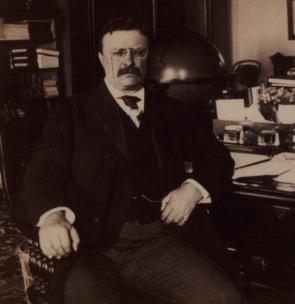

Theodore Roosevelt was one of this generation of international political leaders confronting the new challenges posed by modern industrialism, urbanization, and big business. These challenges, along with conservation and an assertive foreign policy, were the great issues of Roosevelt’s political career. And all of them, in very different ways, were global issues.

Roosevelt followed closely the international discussion on all of these issues. Like Roosevelt, most American progressives were cosmopolitan, following international reforms in the press and through travel. Reformers of all industrial nations participated in these conversations, often in person at international meetings. The transformation of liberalism was a global development, but it is important to remember that in each nation the alignment of political interests, national traditions, and the distribution of political power led to unique resolutions of the problems it faced. It is best therefore not to think of the choices made in the United States as "exceptional," since there was no norm against which our country’s choices could be judged.

Roosevelt moved toward reform slowly, but there was a hint of his inclinations in his first message to Congress in 1901. He said that the nation had been too passive in its attitude and policies toward the accumulation and distribution of power and wealth. Doing so little, he wrote, was "no longer sufficient." He went on to say that "when the Constitution was adopted . . . no human wisdom could foretell the sweeping changes . . . which were to take place at the beginning of the twentieth century." When the framers created the Constitution, "corporate" bodies were small and "localized." "Conditions are now wholly different and wholly different action is called for." If it is a convention of sorts that the older people get the more conservative they get, in Roosevelt’s case, the opposite proves to be true. In his second term, after his announcement that he would not run for re-election, Roosevelt addressed the growing inequality and overweening power of corporations with a new vigor that was almost radical, at least in the view of business and conservative members of the Republican Party.

Roosevelt understood that the challenge of regulating business and ameliorating economic inequality was international in scope. England, he said, was the first to industrialize, and France and Germany "speedily followed suit." Then came the United States, which "got under full headway" after the Civil War. Russia and Spain developed industrial economies later. Roosevelt embraced this industrial progress and did not want America to return to a preindustrial era. But he wanted the government to be more powerful than private corporations. He wanted a national state that was as well planned and efficient as the centralized administration of the great corporations.

Given his philosophy, Roosevelt preferred regulating industry to breaking up corporations. His reputation for "trust busting" was based mostly on his surprising challenge to the Northern Securities Company, a holding company created by the nation’s leading bankers and industrialists. Roosevelt’s preference for mediation rather than conflict figured into his foreign policy as well; his gunboat diplomacy is well known, but he received the Nobel Peace Prize for his mediation in the Russo-Japanese War. He managed other mediations so quietly that at the time there was little public knowledge of his role.

Roosevelt’s awareness of foreign developments convinced him that the United States was moving more slowly than other industrial societies. "Here in America we have in many ways been more backward than in most countries of middle and western Europe, because our situation was such that we could shut our eyes to the unpleasant truths and yet temporarily prosper. But our system, or rather no-system, of attempting to combine political democracy with industrial autocracy . . . has now begun to creak and strain so as to threaten a breakdown." The Hepburn Act in 1906, which conferred radical new power on the Interstate Commerce Commission, was a landmark achievement of the stronger, administrative state that Roosevelt sought. It enabled the government to supervise the financial records of railroad corporations, prescribe uniform bookkeeping, and establish rates. Similarly, the Immunity Act of 1906 required corporate officers to testify about company operations.

Roosevelt believed that the worker should not bear the cost of industrial risk. Thus, workmen’s compensation for individual accidents was one of his top legislative priorities. He started asking for it in 1904, and in 1908 he tried to persuade Congress that the international reputation of the United States was at stake. "It is humiliating that at European international conferences on accidents the United States should be singled out as the most belated among the nations in respect to employer liability legislation." International opinion was important not only to Roosevelt but to reformers in Latin America, Japan, and Italy as well. No one wanted to fall behind what seemed to be a European norm. This sensitivity to the country’s international reputation sometimes influenced domestic legislation. For example, the successful passage of the Pure Food and Drug Act and the Meat Inspection Act in 1906 is usually attributed to the publication of Upton Sinclair’s muckraking novel, The Jungle (1906), which included a few pages describing the unsanitary conditions in the meat-packing industry. Certainly Roosevelt used the book to move Congress, but the legislation was also supported by many in the industry because Germany and Hungary had—on health grounds—refused to accept any imports of American meat.

Roosevelt’s concern for sustainable resources resonates today. His interest in conservation was not mere nostalgia, although he shared an American concern that continued contact with nature was important for the American character. Nor was it purely aesthetic. Neither was he a "preservationist." His policy was utilitarian. He embraced the scientific management of resources for national efficiency. This was another aspect of the enhancement of state capacity and vigor. Roosevelt put the matter on the national agenda in 1908 by appointing a National Conservation Commission, headed by Gifford Pinchot. These actions represented an effort to reverse three centuries of heedless environmental exploitation.

Conservation was also an international concern. All the industrialized nations worried about a possible worldwide shortage of resources, for this would have implications for national power and economic development. Once again, Europeans led the way, and the international influence on American policy was strong. The first notable American conservationists were either Germans or had studied in Europe. Gifford Pinchot, the man appointed to head the US Forest Service in 1905, had studied at the French National Forestry School in Nancy, France, and in Germany.

Viewed in this international or global perspective, we can see that there was nothing unique, or distinctively American, in the progressive reforms in the United States. The industrial nations of the world generally shared common concerns and participated in a common conversation about solutions. Each political outcome, however, was unique, responding to the local political context.

There was also a shared political motivation. Leaders in many industrial countries were concerned that, if they did not respond to the social inequities produced by industrialism, support for socialism would grow. They worked to preserve capitalism by addressing these social concerns. This is revealed in the phrases they often used: social liberalism or social politics. The leaders of industrial nations, encompassing a fairly broad political spectrum, shared this framing of the issue. Thus the language used in 1908 by Taro Katsura, Japan’s prime minister, could have easily come from Theodore Roosevelt:

Socialism is not more than a wisp of smoke, but if it is ignored it will someday have the force of wildfire and there will be nothing to stop it. Therefore it goes without saying that we must rely on education to nurture the peoples’ values; and we must devise a social policy that will assist their industry, provide them with work, help the aged and infirm, and thereby prevent catastrophe.

Thomas Bender is University Professor of the Humanities and professor of history at New York University. His publications include A Nation among Nations: America’s Place in World History (2006), Intellect and Public Life: Essays on the Social History of Academic Intellectuals in the United States (1993), and Community and Social Change in America (1978).