Access this essay as a PDF, including key vocabulary terms and discussion questions, or read the text of the essay below.

A new chapter in voting rights began when the Civil War ended in 1865. Immediately after the war, Black Americans began to leverage federal power to stop state voter discrimination. Historically, states have created the legal requirements for voting, such as being White and male. Over the next fifty years (1870–1920), federal power intervened in the states to end both requirements. At the same time, many state politicians who were against these reforms created new disenfranchisement techniques to skirt federal limits on their earlier methods. Thus began a heated contest in which the immediate question of who should vote lent urgency to the ongoing question of whether states or the federal government controlled voting rights.

A complicated electoral landscape emerged. Some states experimented with women’s suffrage. Congress made limited but crucial expansions when political activists forced their hand, yet states that expanded suffrage in one way often endeavored to exclude other would-be voters with literacy, residency, and other requirements. The result has been a continuous push and pull.

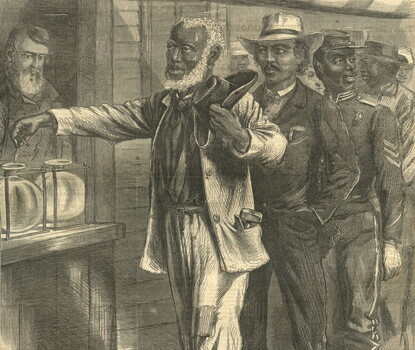

In states unsettled by the Civil War, African Americans saw an opportunity for greater political participation. It was therefore with the example of South Carolina’s state government in mind—specifically, how one legislative house flipped overnight when Black Americans formed a majority in 1868—that Congress pledged ongoing support to crystallize increased Black political power with the Fifteenth Amendment. The first Black congressional delegation arrived in Washington, DC, in 1870, and that same year ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment marked the first time the US Congress had prevented the states from dictating who could vote.

The new Black citizenry was determined to participate. Black men changed the political landscape, and Black male voting expanded dramatically. This trend produced biracial state and local governments across the South, where most Black Americans lived. Yet despite the legal bars to voter discrimination, White vigilante violence haunted Black voters. Many Black male citizens were murdered for daring to vote.

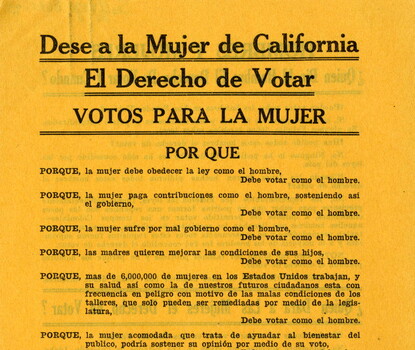

Black women remained barred from the polls, however, because the Fifteenth Amendment said nothing about sex. Striking only race, it left other state requirements untouched. In 1870, all states required voters to be male. That restriction had long fueled women’s outrage. Part of the organized women’s suffrage movement responded to the Fifteenth Amendment with a new idea: a women’s suffrage amendment. Many suffragists opposed it, arguing that enfranchising voters was a state prerogative—and that the idea of a federal amendment to this end was far-fetched.

It took fifty years, but in 1920, women finally got their amendment, the Nineteenth Amendment. Yet by this time, only eight states still barred women’s voting entirely. Activists had already persuaded many states to remove the word “male” from the legislation, allowing women equal voting rights with men. Other states allowed women to vote only in certain types of elections. Still, when the final state ratified the Nineteenth Amendment—by one vote—the face of the US electorate changed dramatically once again.

Like the Fifteenth, however, the Nineteenth Amendment had limited scope. The Nineteenth Amendment denied “the United States or any state” from prohibiting voting “on account of sex.” By 1920, White state politicians had already devised workarounds for federal limits on their determination of the franchise. Between 1890 and the 1910s, White officials across the South, as well as in the North and West, passed new laws such as poll taxes and literacy tests to disenfranchise Black voters. These laws targeted people of color more generally, yet because they never mentioned race, they were technically legal. After 1920, these poll taxes and literacy tests, together with continuing legal and extralegal intimidation, barred millions of women of color—and also men of color—from the polls. These state laws emphatically ended the nation’s first, relatively brief experiment with a robust biracial democracy.

Although both the Fifteenth and Nineteenth Amendments were tremendous achievements, evolution of US voting rights from Reconstruction to 1920 is not only a federal story of triumphant expansion, but also of the disfranchisement of Black voters by various, novel, and often extralegal means.

Lisa Tetrault is an associate professor of history at Carnegie Mellon University. Professor Tetrault specializes in the history of gender, race, and American democracy, with a focus on social movements and memory. Her first book, The Myth of Seneca Falls: Memory and the Women's Suffrage Movement, 1848–1898 (University of North Carolina Press, 2014) won the Organization of American Historians' inaugural Mary Jurich Nickliss women's history book prize.

Voting Rights and Restrictions in Pre-Emancipation America

by Dr. Keri Leigh Merritt (independent scholar)

Access the first and third essays in this series by clicking on the adjacent buttons.

The Battle to Expand Access to the Ballot from 1920 to 2000

by Prof. Michael J. Pitts (Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis)

The Right to Vote Resource Suite

Essays

Read scholarly perspectives on the history of voting rights through essays geared to high school students

Lesson Plans

Learn how individuals and groups attempted to expand access to the vote in "Taking a Stand for Voting Rights: Six States, Six Stories, One Goal."

Digital Exhibitions

Explore our four-part digital exhibition on the history of voting rights, which includes audiovisual elements and interactive maps