Phillis Wheatley: Poet Laureate of the American Revolution

by James G. Basker

Phillis Wheatley (ca. 1753–1784) has appropriately been called “the mother of African American literature,” [1] but with equal justice she can be described as the “poet laureate of the American Revolution.” In the eighteenth century, neither title seemed likely, given her humble beginnings. Phillis arrived in America on a slave ship in July 1761 a seven-year-old child, parentless, speaking no English, naked and terrified, being offered for sale on the Boston docks.[2] She was to prove a prodigy. Purchased by John and Susanna Wheatley, raised and educated in their home, within sixteen months she was fluent in English and by age eleven she was composing poems that were admired around Boston and at least one was copied by a prominent clergyman into his diary.[3] By age fourteen she was publishing occasional poems in local newspapers, and others of her writings were circulating in manuscript, as was the practice of the time. Her “Elegiac Poem on the Death of George Whitefield” in 1770 received acclaim in England and across the American colonies. By early 1772, when she was still only nineteen, she had produced so much poetry that her local supporters and patrons were working with her to publish her poems in book form.

Phillis Wheatley (ca. 1753–1784) has appropriately been called “the mother of African American literature,” [1] but with equal justice she can be described as the “poet laureate of the American Revolution.” In the eighteenth century, neither title seemed likely, given her humble beginnings. Phillis arrived in America on a slave ship in July 1761 a seven-year-old child, parentless, speaking no English, naked and terrified, being offered for sale on the Boston docks.[2] She was to prove a prodigy. Purchased by John and Susanna Wheatley, raised and educated in their home, within sixteen months she was fluent in English and by age eleven she was composing poems that were admired around Boston and at least one was copied by a prominent clergyman into his diary.[3] By age fourteen she was publishing occasional poems in local newspapers, and others of her writings were circulating in manuscript, as was the practice of the time. Her “Elegiac Poem on the Death of George Whitefield” in 1770 received acclaim in England and across the American colonies. By early 1772, when she was still only nineteen, she had produced so much poetry that her local supporters and patrons were working with her to publish her poems in book form.

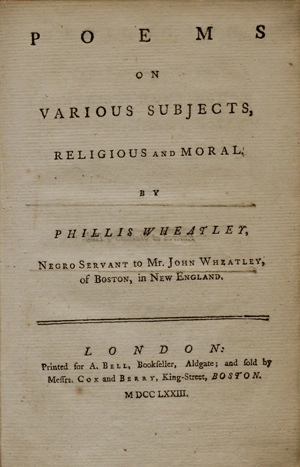

The result was a book manuscript sent off to British publishers in November 1772, her celebrity visit to London in summer 1773, and the publication in London of her volume Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral in September 1773, to wide critical acclaim. Having negotiated her own manumission before leaving London, Phillis returned to Boston a free woman that same month. She left behind in London a coterie of admirers among the British establishment and the prospect of a profitable career as a writer there, to return to the Wheatley family and her friends in New England. The outbreak of the American Revolution made it, in retrospect, an irreversible and fateful decision.

Like the Wheatleys, Phillis was sympathetic to the grievances of the colonists against the Crown. When fighting broke out at Lexington and Concord in April 1775, she decamped with other Bostonian patriots to Providence, Rhode Island. Thus it was from Providence in late October 1775 that she sent her encomiastic poem “To His Excellency General Washington,” which Washington read in his headquarters in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in December 1775. Although the poem is full of praise for Washington, it is less a personal tribute than a political statement. Wheatley did not know Washington nor did she have reason to expect any favor from the general who was in civilian life the master of a slave plantation in Virginia, but by this stage she was fully committed to the American cause, including warfare against the British. Her verses serve as both morale boost and recruitment pitch, as when she lauds the growing numbers of soldiers joining the American army:

In bright array, they seek the work of war,

Where high unfurl’d the ensign waves in air.

Shall I to Washington their praise recite?

Enough thou know’st them in the fields of fight. (ll. 21–24)

For any writer to express such views was, in the eyes of the British, to commit the capital crime of treason, potentially punishable by death. For Wheatley as a Black woman, there was the additional danger that if captured by the British or their loyalist supporters, she might be summarily transported to the Caribbean and sold into slavery. Thus by writing this poem and others like it over the next eight years, Wheatley as much as Patrick Henry or any American patriot was risking her liberty and her life.

Wheatley had allied herself with the American cause since the days of the Stamp Act back in the 1760s. In 1768 she had composed a sharply political poem entitled “To the King’s Most Excellent Majesty on His Repealing the American Stamp Act,” though she diplomatically shortened the title “To the King’s Most Excellent Majesty” when she included it in her London collection of 1773. Also in 1768, Wheatley wrote an allegorical poem called simply “America” in which the powerful mother figure, “Britannia,” is in conflict with her newly grown-up son “Americus.” Certain lines are very telling. For example, in lines 5–6, Wheatley deliberately posits a double meaning, whereby “the weak” are both the subjugated colonists and the enslaved African Americans:

Thy Power, O Liberty, makes strong the weak

And (wond’rous instinct) Ethiopians speak

Thus the prospect of liberty makes not only the colonies but enslaved Black people assert their strength, speak out, and seek their freedom. Wheatley labels the son Americus a “rebel” (“What ails the rebel, great Britannia cried”) who further on in the poem “weeps afresh to feel this iron chain” of tyranny. The poem closes with a call for Britain to wake up and treat its unhappy son more kindly: “Turn, O Britannia, claim thy child again.” Otherwise, Wheatley delicately hints, the parent may lose its child forever.

In 1770, the events that Paul Revere taught Americans to remember as “the Boston Massacre” moved Wheatley to write a poem to protest the loss of American life, including Crispus Attucks, the first person of color to die in the escalating conflict. She titled the poem “On the Affray in King’s Street, on the Evening of the 5th of March” and it was listed in a Boston newspaper ad in 1772, but unfortunately the full text was never published.[4] Modern scholars point to twelve lines published anonymously in 1770, a week after the massacre, as Wheatley’s first response to the event, and probably an excerpt from or early version of the lost poem. The lines of lament for these victims of British gunfire close with a patriotic flourish:

Long as in Freedom’s Cause the wise contend

Dear to your unity shall Fame extend;

While to the World, the letter’d Stone shall tell,

How Caldwell, Attucks, Gray, and Mav’rick fell.[5]

Wheatley’s modesty in printing these lines anonymously deepens the sense of her serving a purpose larger than herself, what she calls “Freedom’s Cause.”

In 1772, Wheatley wrote one of her most important political poems, addressed “To the Right Honourable William, Earl of Dartmouth,” recently appointed as the British governor of colonial Massachusetts. With the characteristic boldness evident in so many of her poems, directly addressing a powerful White male authority figure, Wheatley welcomes the new governor as an enlightened leader who will hear the colonists’ grievances, remedy their wrongs, and restore good government. Whether sincere praise or subtle manipulation, Wheatley’s lines develop a parallel between the lawless oppression of the colonies and the enslavement of Africans. In one of the most personally revealing and emotional passages in all of her writings, Wheatley asserts her unique authority as a Black person to speak about freedom and tyranny:

Should you, my lord, while you peruse my song,

Wonder from whence my love of Freedom sprung,

Whence flow these wishes for the common good,

By feeling hearts alone best understood,

I, young in life, by seeming cruel fate

Was snatch’d from Afric’s fancy’d happy seat:

What pangs excruciating must molest,

What sorrows labour in my parent’s breast?

Steel’d was that soul and by no misery mov’d

That from a father seiz’d his babe belov’d:

Such, such my case. And can I then but pray

Others may never feel tyrannic sway? (ll. 20–31)

Wheatley grounds her love of freedom and her patriotism, paradoxically, in her life experience as an enslaved person.

Thus by the time Wheatley wrote her poem of praise for the installation of General Washington as commander in chief of the American forces in 1775, her commitment to the American cause was well established. The ardor of Wheatley’s patriotism contributed to Washington’s decision both to invite her to visit him at his headquarters in Cambridge (the only time he ever made such an invitation to a Black person) and to charge his aide, Joseph Reed, with publishing her poem in a pro-American newspaper. Reed, who opposed slavery and would help abolish it in Pennsylvania in 1780, chose the Virginia Gazette in which to publish Wheatley’s poem “To His Excellency General Washington” (March 30, 1776). This was a strategic political decision. Since Lord Dunmore’s proclamation in November 1775, offering freedom to any enslaved men who came over to fight on the British side against the American rebels, Virginia had been experiencing a rolling “insurrection” with hundreds escaping to take up arms. The publication of Wheatley’s poem was intended to calm the situation, by presenting fearful Whites and wavering Blacks with a dramatic example of a patriotic African American. In ways she never anticipated, Wheatley became a political actor in one of America’s worst crises. Thomas Jefferson was still smarting from the widespread defection of enslaved people to the British side when he embedded a complaint about “domestic insurrections” in the final version of the Declaration of Independence.

Wheatley continued to write explicitly political poems throughout the war. In December 1776 she heard about the capture of General Charles Lee and composed a poem in his honor in which she also included a tribute to Washington. Remarkably, given Lee’s rivalry with Washington, which clearly was unknown to Wheatley, in the closing lines she has Lee praise Washington as Lee defies the British:

Yet those brave troops innumerous as the sands

One soul inspires, one General Chief commands

Find in your train of boasted heroes, one

To match the praise of Godlike Washington.

Thrice happy chief! In whom the virtues join,

And heaven-taught prudence speaks the man divine. (ll. 63–68)

Wheatley sent the poem off to James Bowdoin, president of the Massachusetts Provincial Congress. But Bowdoin, who was aware of Lee’s efforts to undermine Washington, held it back from publication (it turned up later in his papers) and saved Wheatley from an embarrassing political mistake.

Two years later, Wheatley’s elegy “On the Death of General Wooster” in 1778 celebrated an American war hero who died in battle, while it also served as a personal token of condolence to his widow Mary Wooster, whom Phillis knew as a friend and supporter. Mary and her late husband were opponents of slavery, which Wheatley acknowledged by having the spirit of General Wooster speak from beyond the grave to criticize America for maintaining slavery while fighting for freedom:

But how, presumptuous shall we hope to find

Divine acceptance with th’ Almighty mind—

While yet (O deed ungenerous!) they disgrace

And hold in bondage Afric’s blameless race?

Let virtue reign — And thou accord our prayers

Be victory our’s, and generous freedom theirs. (ll. 27–32)

Once again, Wheatley explicitly links the ideal of freedom from British tyranny with the ideal of freedom for enslaved African Americans. Wheatley clearly hoped that Americans would see both of these as political and moral imperatives.

After 1779, Wheatley endured financial and personal setbacks, and produced few writings of any kind. But two of the very last poems she ever wrote were devoted to the American cause and its heroes. In December 1783, Wheatley composed “An Elegy Sacred to the Memory of the Rev’d Samuel Cooper, D.D.,” a prominent clergyman and patriot. Pastor of the Brattle Street Church in Cambridge, Massachusetts, Cooper had ministered at various times to John Hancock, Samuel Adams, Joseph Warren, John Adams, and many others among the American political and military leadership. In 1783 Cooper was one of the inner circle to whom Washington entrusted the editing of the final draft of the Treaty of Paris. In her elegy, rather than expressing personal sorrow, Wheatley speaks in the voice of a public poet commemorating a hero on behalf of the nation:

Thy Country mourns th’ afflicting hand divine

That now forbids thy radiant lamp to shine

Which, like the sun, resplendent source of light

Diffus’d its beams, and chear’d our gloom of night. (ll. 23–26)

Wheatley’s poem stresses the dual role that Cooper played in the Founding Era, as both a religious and political influence. She assures the departing spirit of Cooper that his “deathless name” will live forever “in thy Church and Country’s love” (ll. 38–39).

Before she died prematurely at the age of thirty-one, Wheatley was inspired by the American victory and the achievement of independence to produce the most visionary and uplifting of all her patriotic writings. Entitled “Liberty and Peace,” the poem was published as a broadside over her married name of “Phillis Peters” in mid-1784. It is a soaring and hopeful poem about America after independence and its future place among the nations of the world. Comparing America to a “new-born Rome” (l. 22), she builds the 64-line poem to a closing prophecy of greatness for America and the light the new nation will shine on the world:

Auspicious Heaven shall fill with fav’ring Gales

Where e’er Columbia spreads her swelling Sails;

To every Realm shall Peace her Charms display,

And Heavenly Freedom spread her golden Ray. (ll. 61–64)

Wheatley died suddenly of cholera in December 1784, a few months after this poem appeared. It turned out to be her parting gift to the new country, a country that she had helped create with her imaginative talent and patriotism, but which is only now, centuries later, beginning to appreciate her contributions as a hero of the American founding. Wheatley’s entitlement to be called the “Poet Laureate of the American Revolution” is fully justified. No other poet of the time was invited to George Washington’s headquarters, no poet was as persistent in supporting the American cause in her verse from the Stamp Act in the 1760s down through the Revolutionary War all the way to independence in the 1780s, and no other poet risked more in doing so.

This essay was originally published in the Gilder Lehrman Institute’s Women Who Made History: Historians Present Documents from the Gilder Lehrman Collection (2020).

James G. Basker is the president of the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History and Richard Gilder Professor of Literary History at Barnard College, Columbia University. His publications include Amazing Grace: An Anthology of Poems about Slavery, 1660–1810 (Yale University Press, 2002) and American Antislavery Writings: Colonial Beginnings to Emancipation (Library of America, 2012), as well as scores of essays and educational booklets on various topics in English and American history and literature. His anthology Black Writers in the Founding Era, 1760–1800 is forthcoming from the Library of America in September 2022.

[1] Henry Louis Gates, Jr., The Trials of Phillis Wheatley: America’s First Black Poet and Her Encounters with the Founding Fathers (New York: Basic Civitas Books, 2003), 30.

[2] Vincent Carretta, Phillis Wheatley: Biography of a Genius in Bondage (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2011), 6–14. All biographical details from Carretta unless otherwise noted.

[3] Carretta, 46.

[4] Carretta, 72 and note 41.

[5] Boston Evening-Post , March 12, 1770, 4. The twelve untitled lines are attributed to Wheatley by Antonio T. Bly, “Wheatley’s ‘On the Affray in King Street,’” Explicator 56, no. 4 (Summer 1998): 177–180 and William H. Robinson, Phillis Wheatley and Her Writings (New York: Garland, 1984), 455.