Perils of the Ocean in the Early Modern Era

by Robert C. Ritchie

A traveler considering an ocean voyage around 1600 had much to contemplate. Voyage by voyage, explorers and colonists alike needed knowledge about the seas and lands in the Atlantic world. Unfortunately, information was never shared freely between nations, who treated such knowledge as secret in order to hinder the ambitions of others. Nevertheless a serious traveler could acquire information aiding an assessment of the risks and dangers ahead through maps, travel accounts, adventure stories, and mariners’ tales. If one was an anxious individual, there were enough terrors to cause a serious panic attack.

Acquiring a map was a good way to start, although it could be unsettling. The distances were vast, and behind often barely known coastlines there were large swaths of terra incognita.

These inland areas were often detailed with images of native peoples who were strange to behold. Some were depicted with the heads of dogs, heads in the middle of their chests, and other oddities. Some images denoted cannibalism. Once a potential traveler’s eyes left the land the images on the sea were worse: decorating the edge of many maps were various great and awful beasts that looked capable of swallowing a ship in a single gulp. These were creatures imagined to have emerged from the primeval ooze that remained after the great flood. By sea and or land, maps could easily cause the wary traveler to reconsider their coming voyage.

The edges of these maps depicted another danger for the seventeenth-century ocean traveler: wind. Often winds were drawn as classical heads with their cheeks puffed, representing what was essential in the age of sail. Favorable winds that pushed the ships toward their destination were a mariner’s prayer and shown as well. Knowledge of the Atlantic’s wind systems was critical to the master, or pilot, of the ship and its captain. Local winds and currents could lead to wrecking the vessel. It took some time for Spanish navigators to figure out that the Gulf Stream pouring out of the Gulf of Mexico and heading north was a benign current that led ships to the westerly trade winds that swept travelers back to Europe. But timing was everything in taking advantage of this system. In the late summer through November, the warm waters of the tropics nurtured tropical depressions that all too often turned into the dreaded hurricanes. Storms were a common danger when sailing and many could be survived by judicious handling of the ship, but hurricanes were another matter. Their winds tore sails off ships, and as they rushed over the surface of the sea they built waves to unimaginable heights, stressing wooden ships, shattering masts, and opening up seams in the hull, causing even well-manned and sturdy warships to sink. Even if a traveler survived the experience, hurricanes most often left a ship an unmanageable hulk adrift in a still-turbulent sea. Ordinary winds could also cause problems. Contrary winds kept ships bottled up in port. Many ships had a difficult time sailing into the wind. At best it might mean endless tacking from side to side across the face of the wind, requiring a great deal of work for very little headway—best to stay in port or anchor to wait for more suitable conditions. Unfortunately, this meant using valuable food and water needed for the voyage. Once released by the winds after days or weeks spent waiting, the voyage could get underway.

To the weary ocean traveler in 1600, a respite from winds might be an answer to prayers, but here again there were dangers. A lengthy calm or falling into windless areas or "doldrums" brought the same problem as contrary winds—food and water were used up and rationing called for until the winds stirred. The prayers uttered for favorable winds at the beginning of a voyage were fervent and necessary.

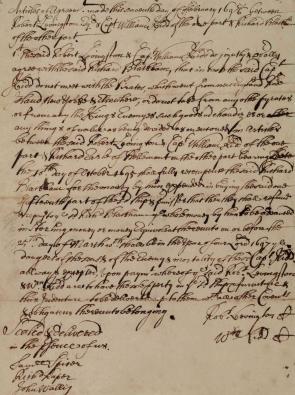

A wise captain in this age kept a sharp lookout at all times. The ship sailing innocently toward you could well be a pirate or privateer: both were endemic at the time. European states were frequently at war. Attacking private vessels as a way of hurting a rival state’s commerce was common. A proper privateer was commissioned by a government to attack the shipping of the enemy. The individual or group obtaining the commission was expected to raise the funds to outfit and man a ship. Should the privateer be successful, all the ships and cargoes that they captured had to be returned to a port where an admiralty court would condemn the ships and cargo and thus turn them over to the privateer as legally captured and ready for sale. The only redress the victim had was to complain to his own government in hopes of compensation, but this was unlikely. Some compensation was possible as this era was witnessing the expansion of the insurance business. Some governments would issue a commission of reprisal that allowed the victim to seize vessels and cargoes of equal value from the enemy—yet this would work only if one had the wherewithal to outfit a new fighting vessel. Privateering could be highly profitable, and some ports, such as Dunkirk and St. Malo, were famous for sending out deadly and successful captains.

Pirates did not seek commissions. Instead they went to sea ready to capture ships of all nations. A successful pirate ship looked like any other trading vessel as pirates preferred surprise to long gunfights. The fact was that few merchant vessels carried much armament. The seamen had no investment in the cargo and were reluctant to fight—unless it was Spanish Catholics versus English Protestants. Then both sides could be roused to battle. Otherwise the pirates used surprise and gunfire to cow the crew, then boarded to take what they needed or wanted. Often after taking food and water they would loot anything of value, even such mundane things as salt. All things could have a value to them; merchants were always willing to buy cheap merchandise. Those with money or real valuables had the most to fear from pirates, who compelled cooperation by maiming, torturing, or killing one or two people in order to convince the rest of the need to be truthful. Often pirates would try to recruit new men before abandoning their victims. Or they would simply burn the ship or commandeer it for their own.

The most dreaded were the Barbary pirates. They sailed out of North African ports such as Tunis in fast galleys and terrorized the Mediterranean for centuries, but in early modern times they raided as far afield as the English Channel and Iceland. Many captives of the Barbary pirates were sold as slaves in North Africa or given the opportunity to obtain a ransom. Christian communities created a "Turk’s tax" to ransom these captives. Most of those ransomed came from families that were wealthy. Those without the means to be ransomed were sold into slavery with Muslim families or consigned to the galleys to row for the rest of their days. Such fates made the sight of a galley at sea a fearsome thing.

While pirates or privateers could appear at any time, they tended to cluster around prominent navigational sites, close to port or in well traveled areas. On a long journey across the empty ocean, one could feel relatively safe. Approaching land brought rising tensions and the sight of any sail forced the captain to prepare to press on and try to escape if the other ship was not readily identifiable as a friend. Of course, pirates knew how to look friendly. Not until the ship was safely berthed could the thought of pirates be set aside. Until then they were a very real element of danger in any voyage.

The colonist about to embark on an ocean voyage might be filled with trepidation on first view of his or her ship, as most merchant ships were quite small. Only the fighting ships of the time were large. A standard merchant vessel was about 200 tons capacity—approximately eighty feet long and twelve-to-fifteen feet wide. However, ships of fifty and seventy-five tons were common and had much smaller dimensions. To a landsman, the idea of challenging the mighty ocean on such a ship was terrifying. Once on board, the reality of the conditions faced by passengers was apparent. There were no cabins. One had to pile up baggage in a comfortable spot in the hold as space for living, sleeping, and eating was confined there. The busy crew cared little for the passengers’ physical comfort. The passengers, if anything, were objects of humor to the crew and not to be taken seriously. The first real waves brought on the inevitable seasickness, and the only place to be sick was in the hold. The crew did not like passengers lolling around the deck. The bathroom was a roughly enclosed "head" on the side of the ship, and in rough weather as the ship pitched and rolled, it was safer to go on the ballast at the very bottom of the hold. Day by day the interior of the ship became ever more smelly and unbearable, even to people attuned to a more odoriferous environment. The festering mess in the hold also brought on infectious diseases that could lay passengers and crew low, increasing discomfort. In addition, the passage of every day without fresh food brought on symptoms of bleeding gums, loss of teeth, and a deadly lethargy that overtook the sufferers.

As the voyage continued, prayers for the sight of land grew more fervent. Navigational instruments were primitive: most captains relied on dead reckoning. Sometimes they could be disastrously wrong. A famous incident occurred when an expedition left Havana with a pilot sailing directly west to Mexico but ending up instead on the coast of Florida; for some time the travelers believed they were in Mexico. Or recall the ship sailing to Virginia that discovered Bermuda by crashing into it. More often than not and rarely on schedule, the coast was sighted and the harbor enclosed around the ship, putting everyone out of their misery.

Africans who made the journey to the New World or to Europe traveled, with very few exceptions, under very different circumstances. The appalling middle passage made the travails of regular passengers described above insignificant. Stuffed into every corner of the slave ship, denied adequate food, water, exercise, and sanitation facilities, Africans were given a preview of the brutality and horror awaiting them when they reached port.

Despite the dangers and conditions for ocean travel in the early modern era, hundreds—and as time wore on thousands—of ships managed to make voyages across the Atlantic from east to west and north to south. This was a testimony to the sturdy ships and mariners who brought their passengers through the humbling seas.

Robert C. Ritchie is the W. M. Keck Foundation Director of Research at the Huntington Library and Art Gallery. His contributions to maritime history include Captain Kidd and the War against the Pirates (1986).