Painting Independence in Boston: Prince Demah

by Jennifer Van Horn

Between January and November 1773 an advertisement appeared in the Boston News-Letter. It alerted readers: “At Mr. M’Lean’s, Watch-Maker, near the Town-House, is a Negro Man whose extraordinary Genius has been assisted by one of the best Masters in London; he takes Faces at the lowest Rate. Specimens of his Performances may be seen at said Place.” The advertisement identified a Black portrait painter at work in Boston before the American Revolution, yet the artist’s identity remained a mystery. It was not until the 2010s that scholars identified him as Prince Demah (ca. 1745–1778). Demah is the first enslaved portraitist of African origin or descent in North America whom we can identify by name.

Between January and November 1773 an advertisement appeared in the Boston News-Letter. It alerted readers: “At Mr. M’Lean’s, Watch-Maker, near the Town-House, is a Negro Man whose extraordinary Genius has been assisted by one of the best Masters in London; he takes Faces at the lowest Rate. Specimens of his Performances may be seen at said Place.” The advertisement identified a Black portrait painter at work in Boston before the American Revolution, yet the artist’s identity remained a mystery. It was not until the 2010s that scholars identified him as Prince Demah (ca. 1745–1778). Demah is the first enslaved portraitist of African origin or descent in North America whom we can identify by name.

Held in bondage by a Marlborough, Massachusetts merchant and his wife, Henry and Christian Barnes, Prince Demah had a brief but remarkable career. Demah’s path to becoming a painter was circuitous and unusual, spanning the Atlantic Ocean and the Imperial Crisis. Demah and his mother, Daphney, were baptized at Trinity Church in Boston in 1745. Whether they were born into slavery in North America or had been kidnapped and suffered the transatlantic slave trade is unknown. Daphney was enslaved by the Barnes family and worked as a cook whereas Demah became a sailor. This was a common form of labor; approximately a quarter of all enslaved men in New England engaged in nautical work.

The Barneses decided to purchase Demah in his twenties—likely at his mother’s urging—for the purpose of having him trained as a portrait painter. Christian Barnes, a copious letter writer, described how she and her husband Henry asked Demah to copy a portrait of her brother and then to produce an image of her as a test of his skill. They were convinced by “the force of [Demah’s] natural Genius” and purchased him in 1769. Christian Barnes recorded Daphney Demah’s joy at reuniting with her son.

The Barneses decided to purchase Demah in his twenties—likely at his mother’s urging—for the purpose of having him trained as a portrait painter. Christian Barnes, a copious letter writer, described how she and her husband Henry asked Demah to copy a portrait of her brother and then to produce an image of her as a test of his skill. They were convinced by “the force of [Demah’s] natural Genius” and purchased him in 1769. Christian Barnes recorded Daphney Demah’s joy at reuniting with her son.

Prince Demah worked as a domestic servant for the Barneses and also practiced artmaking. The Barneses were committed to his education. In 1770, Henry Barnes brought Demah with him to London where he received training from Robert Edge Pine, a history painter and portraitist, for approximately eight months. Pine was one of the most successful painters in London in the period. In Pine’s London studio Demah would have learned to prepare oil paints, to ready a canvas, and to paint a sitter’s likeness. He also would have seen how an artist conducted his business and his professional demeanor. Scholars have argued that Pine might have agreed to teach Demah because of Pine’s own possible mixed-race status.

Even as Demah’s artistic skills increased, Henry Barnes restricted his movements and limited his opportunities for freedom. In a letter to his friend Elizabeth Murray on February 12, 1771, Henry noted that he feared Demah might “attempt his freedom,” admitting “I do not let him converse with any of his own colour here.” Indeed, Henry wrote “his life & situation are so precarious if he should even attempt his Freedom it would give me such a disgust to him I should not overlook it.” In London, Demah would have discovered a community of Free Black people. Barnes, however, made sure he could not form friendships with them or gain their support. Demah also would not have met many Afro-British men engaged in artmaking. Although London was the artistic capital of the British empire, the profession of the artist was overwhelmingly restricted to White men. As a Black artist Demah was as unusual in London as he was in Massachusetts.

Upon Henry Barnes and Prince Demah’s return to Massachusetts, the Barneses set him up as a portrait painter in nearby Boston. Then the second-largest city in British North America, Demah would be more likely to gain clients there than in the suburban Marlborough. The Barneses rented space in a Boston watchmaker’s shop and advertised Demah’s skills in a local newspaper. They touted his training from a London artist and low fees, and capitalized on his Blackness; in their words Demah was a “Negro Man” with “extraordinary Genius.” The Barneses anticipated readers’ surprise at a Black man possessing artistic skill, an attitude formed by racist natural historians and philosophers who preached that African Diasporic people supposedly lacked the capacity for artmaking. The Barneses intended to make money from Demah’s portrait painting. It appears that they kept the fees paid by Demah’s patrons, similar to other enslavers who rented out those people they enslaved and then accepted the wages paid to them.

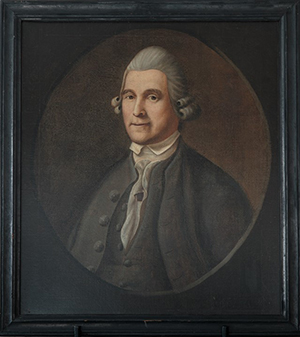

Only three paintings Demah created are known to survive today. These are portraits of his enslavers, the Barneses, and a painting of merchant William Duguid, now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s collection. Thanks to a surviving receipt and Christian Barnes’s copious letters we know that Demah painted at least six more portraits and that he also created works in pastel (a more ephemeral medium of crayon on paper), including a self-portrait, all of which have been lost or remain unidentified.

Only three paintings Demah created are known to survive today. These are portraits of his enslavers, the Barneses, and a painting of merchant William Duguid, now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s collection. Thanks to a surviving receipt and Christian Barnes’s copious letters we know that Demah painted at least six more portraits and that he also created works in pastel (a more ephemeral medium of crayon on paper), including a self-portrait, all of which have been lost or remain unidentified.

Given the tumultuous decades in which Demah worked, it is perhaps surprising that any of the artworks he created survived. Demah painted in Boston amidst the political resistance spurred by the Stamp Act, and in the early years of the American Revolution. Indeed, Demah’s adult life was marked by political conflict. The Barneses were Loyalists (supporters of the British crown) and left Massachusetts in 1775. At that point Prince and Daphney Demah gained their freedom. It is unknown whether they seized freedom for themselves, as many African Americans in the city did, or if they were manumitted by the Barneses before the family’s departure.

Two years later, in April 1777, Demah enlisted in the Massachusetts militia and fought for the American cause. Tragically, he died in late March 1778, probably a victim of an infectious disease. In his will he identified himself as “Prince Demah, limner,” or painter. Members of the Continental Army occupied the Barnes family home in Marlborough. The six “family pictures” the Barneses had left behind, many of which Demah painted, fell victim to attack. Legend holds that soldiers slashed the hearts of Henry and Christian Barnes in Demah’s portraits, damage that is still visible in Christian’s image. Daphney Demah retained at least one portrait by her son of the Barneses’ deceased daughter and was supported by a stipend taken from the Barneses’ confiscated estate.

Two years later, in April 1777, Demah enlisted in the Massachusetts militia and fought for the American cause. Tragically, he died in late March 1778, probably a victim of an infectious disease. In his will he identified himself as “Prince Demah, limner,” or painter. Members of the Continental Army occupied the Barnes family home in Marlborough. The six “family pictures” the Barneses had left behind, many of which Demah painted, fell victim to attack. Legend holds that soldiers slashed the hearts of Henry and Christian Barnes in Demah’s portraits, damage that is still visible in Christian’s image. Daphney Demah retained at least one portrait by her son of the Barneses’ deceased daughter and was supported by a stipend taken from the Barneses’ confiscated estate.

Although Demah was only a painter for a brief period, his career challenged the White-dominated profession of artmaking. Like his military service, which demonstrated his commitment to freedom from tyranny, Demah’s work as a painter defied expectations and enabled him to make his mark.

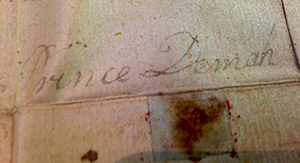

A note about naming: Throughout this essay I use the name “Prince Demah” as it is the name the artist employed in his will. He signed the William Duguid portrait “Prince Demah Barnes,” but seemingly dropped the surname of his former enslavers (Barnes) once he had the opportunity. This naming choice honors his decision.

Select Bibliography

Christian Barnes Papers, 1768–1784, Library of Congress.

DuBois Shaw, Gwendolyn. Portraits of a People: Picturing African Americans in the Nineteenth Century. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2006.

Farrington, Lisa A. “Black or White? Racial Identity in Nineteenth-Century African American Art,” Notes in the History of Art 31:3 (Spring 2012): 5–12.

Gikandi, Simon. Slavery and the Culture of Taste. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2011.

Hardesty, Jared Ross. Unfreedom: Slavery and Dependence in Eighteenth-Century Boston. New York: New York University Press, 2016.

Kamensky, Jane. A Revolution in Color: The World of John Singleton Copley. New York: W. W. Norton and Company, 2016.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art Online Catalogue, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection.

Nash, Gary B. “The African Americans’ Revolution,” Oxford Handbook of the American Revolution, eds. Edward G. Gray and Jane Kamensky. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012, 250–270.

Peck, Amelia and Paula M. Bagger. “Prince Demah Barnes: Portraitist and Slave in Colonial Boston,” The Magazine Antiques, 182:1 (January/February 2015):154–158, http://www.themagazineantiques.com/articles/prince-demah-barnes-1/.

Van Horn, Jennifer. “Prince Demah and the Profession of Portrait Painting,” Beyond the Face: New Perspectives on Portraiture, ed. Wendy Wick Reaves. London: National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian with D. Giles, Ltd., 2018, 42-59.

Van Horn, Jennifer. Portraits of Resistance: Activating Art During Slavery. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2022.

Jennifer Van Horn is professor of art history and history at the University of Delaware. She is the author of The Power of Objects in Eighteenth-Century British America (University of North Carolina Press, 2017) and Portraits of Resistance: Activating Art During Slavery (Yale University Press, 2022).