No Way Out: Lord Cornwallis, the Siege of Yorktown, and America’s Victory in the War for Independence

by James Kirby Martin

Early on the morning of October 17, 1781, Lieutenant General Charles, Lord Cornwallis, found himself hunkered down in a cave near the southern shoreline of the York River. Above him was the disintegrating hamlet of Yorktown, Virginia, now being systematically bombarded into rubble by American and French cannon fire. Cornwallis understood that imminent surrender was the certain fate of his entrapped military force, an army that consisted of about 8,000 British, Hessian, and loyalist soldiers, in addition to wives, consorts, and even children. An attempted breakout had failed the previous evening. A sudden tropical storm disrupted an effort to move his army northward across the York River to Gloucester Point—and possible escape. Now with the ground continually shaking all around him, Cornwallis prepared to order a white flag hoisted above his battered entrenchments, even as he reckoned with the reasons why his army had gotten into such a hopeless position.

Early on the morning of October 17, 1781, Lieutenant General Charles, Lord Cornwallis, found himself hunkered down in a cave near the southern shoreline of the York River. Above him was the disintegrating hamlet of Yorktown, Virginia, now being systematically bombarded into rubble by American and French cannon fire. Cornwallis understood that imminent surrender was the certain fate of his entrapped military force, an army that consisted of about 8,000 British, Hessian, and loyalist soldiers, in addition to wives, consorts, and even children. An attempted breakout had failed the previous evening. A sudden tropical storm disrupted an effort to move his army northward across the York River to Gloucester Point—and possible escape. Now with the ground continually shaking all around him, Cornwallis prepared to order a white flag hoisted above his battered entrenchments, even as he reckoned with the reasons why his army had gotten into such a hopeless position.

Lord Cornwallis had been born into the highest ranks of British society in 1738. He attended the best schools, including Eton and later Cambridge University, and then chose to pursue a military career. Unlike many of the titled nobility that filled the upper ranks of the British military establishment, Cornwallis took time to study the science of conducting warfare at the well-known military academy in Turin, Italy. His father purchased a military commission for him as an ensign in the 1st Foot Guards, and Cornwallis soon traveled to Germany where he distinguished himself in combat during the height of the Seven Years’ War (also known as the French and Indian War in its North American phase).

Cornwallis also pursued a political career in Parliament, getting elected to the House of Commons before being elevated to his family’s seat in the House of Lords to succeed his father, who died in 1762. Amazingly, given his later martial actions in America, he opposed various legislative plans, including the Stamp Act, designed to bring Britain’s American colonies under greater imperial control. As an apparent friend of the colonists, of which there were few in the House of Lords, Cornwallis winked at American resistance. But when resistance turned to open rebellion and warfare in the wake of the Battles of Lexington and Concord in April 1775, he did not hesitate to accept a general’s commission from King George III and sail for America, arriving in early 1776.

Many of the key British generals suffered from a lack of martial aggressiveness. They considered the colonists their inferiors, the kind of fainthearted nobodies who would wither and run when they had to face massed British arms. By virtue of his education and training as a peer of the realm, Cornwallis was no fawning admirer of the Americans, but he would not allow his condescension to hold him back from acting decisively, with almost a reckless form of pugnacity, in his attempts to suppress the rebellion.

Stated differently, Cornwallis was not timid about going after rebellious colonists. He displayed his aggressiveness in various actions directed against Washington’s Continental forces in 1776 and 1777. A year later, he returned to England to care for his beloved, sickly wife. When she passed away in February 1779, Cornwallis was despondent with grief. A few months later, hoping to divert his mind from his emotional pain, he sailed back to America to press on with efforts to put an end to the American rebellion.

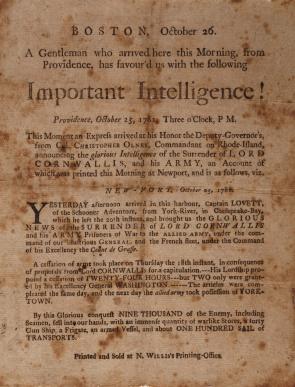

Even before Cornwallis returned to England, British strategy aimed at winning the war had shifted dramatically. Up until 1778 much of the effort had focused on knocking out Washington’s army as well as re-conquering New England, the initial seat of the rebellion. While Washington’s troops took a series of poundings but continued to survive in the middle states, major combat in upstate New York resulted in a critical patriot triumph at Saratoga, about thirty miles north of Albany along the Hudson River. On October 17, 1777, after two earlier pitched battles, a British army of near 5,000 troops, commanded by overconfident, slow-moving, and indecisive "Gentleman" Johnny Burgoyne, surrendered to the Americans.

This impressive victory set in motion the process by which France, an ancient enemy of England, signed an alliance agreement with the American rebels in February 1778. The French both recognized American independence and promised to stand as a good and faithful ally of the patriot cause. Heretofore, the French had secretly aided the Americans with cash subsidies, loans, and war goods. Now they would do much more, including providing invaluable land and naval forces that would give their American allies a critical martial advantage in subduing British forces in North America, as Cornwallis would ultimately experience at Yorktown.

French intervention turned what had been a civil war into an international conflict. The French navy could attack valuable British possessions almost anywhere, including such targets as the English West Indian sugar islands. The French even gave thought to mounting a sea offensive against England itself. In response, England’s wartime leaders decided to withdraw troops from North America for defense of other imperial holdings.

The possibility of troop reductions, literally taking the eye off the American rebels, resulted in a new strategic approach designed to snuff out the rebellion. Some evidence suggested that the southern colonies were teeming with loyalists, perhaps up to 50 percent of the population. So the South became the new focal point of British strategy. With loyalists serving under British arms, manpower shortages would be resolved. The new plan was to recapture and subdue one former colony after another, starting with Georgia, then proceeding northward through the Carolinas and into Virginia and beyond. British-loyalist forces were to move forward in careful steps, making sure of the full restoration of royal authority before continuing the advance. The southern strategy got off to a successful start with a campaign that brought Georgia back into the British fold at the end of 1778.

Returning to New York City, the main base of British operations, in the summer of 1779, Cornwallis would serve as second in command under Henry Clinton. The two men had very different temperaments. Clinton, seemingly mentally immobilized by the dispersal of British troops from North America, did not have faith that the rebellion could be subdued without an infusion of additional British forces. He had little confidence in loyalists as martial substitutes. Cornwallis, on the other hand, was ready to make due with whatever resources, including loyalists, were available to him. Clinton was passive and indecisive. Cornwallis was aggressive and decisive. In addition, the two generals did not trust each other. Ever suspicious of each other’s motives, Clinton wondered whether Cornwallis’s return to England had really been about getting some form of independent command. For his part, Cornwallis had secured a commission to replace Clinton, should the latter decide to resign and go home. Clinton had more than once threatened to do so, even asking in 1779 to be relieved of command, a request that King George III pointedly turned down.

Despite their differences, the two generals worked together effectively in a large-scale seaborne siege campaign to recapture Charleston, South Carolina. This second step in the British southern strategy succeeded in May 1780, resulting in the capture of some 5,500 defenders under the commander of the Continental Army’s Southern Department, Major General Benjamin Lincoln. Before Clinton sailed back to New York, leaving Cornwallis in charge of further campaigning in the South, the two generals were bickering over details, as they had done on occasion earlier in the war. The revival of ill feelings would lead to all sorts of communication problems as Cornwallis acted on his own in a virtual independent command while Clinton hovered about New York City and its environs fretting about possible rebel actions against British defensive positions there.

Advancing by careful steps, as called for by the southern strategy, was alien to Cornwallis’s temperament. Now on his own, he chose to go after rebel resisters with little concern about securing the ground behind him. When he saw an opportunity in mid-August 1780 to wipe out a newly forming patriot army under Major General Horatio Gates, who had replaced the captured Lincoln as the southern Continental commander, he virtually annihilated this force at Camden, South Carolina. Next Cornwallis marched into North Carolina and divided his troops to chase after smaller units of rebel resisters, including partisan bands operating under the likes of "Swamp Fox" Francis Marion behind him in South Carolina. Yet another rebel commander, the brilliant Major General Nathanael Greene, appeared in North Carolina. Greene read his opponent well. He first divided his own force, then waved his small rebel contingent at the ever aggressive Cornwallis, who grabbed at the bait and chased after Greene all the way north into southern Virginia, then back to central North Carolina, before the two forces squared off in a bloody but indecisive battle at Guilford Court House on March 15, 1781.

Once focused on Greene, Cornwallis did not bother to send communications to Clinton until after he marched his exhausted force from Guilford Court House to the North Carolina coast. As he rested and refitted his army, Cornwallis decided on his own authority to advance into Virginia rather than to pull back to Charleston. From his correspondence, he seemed to be looking for a climactic, set-piece, winner-take-all battle with the rebels. He also spoke of cutting off supplies flowing south from Virginia in support of Greene’s army and partisan units operating in the Carolinas. In his apparent distress, if not anger about not yet crushing his rebel opponents, Cornwallis ignored the possibility that he was marching his army into an inescapable trap.

People and the course of events now seemed to conspire against Cornwallis. Certainly one source of problems was an agitated, confused, angry Clinton, disturbed by his subordinate’s lack of communication and his unauthorized decision to invade Virginia. Clinton began sending Cornwallis contradictory instructions, more or less written as suggestions rather than specific orders. Cornwallis made some effort to follow Clinton’s waffling messages, first by trying to find a defensible position where Royal Navy vessels could sail into Chesapeake Bay and pick up troops not needed to defend that location. When some 2,000 Hessians arrived in New York to reinforce Clinton, which eased his worries about having enough soldiers to defend New York City from the hovering combined Franco-American force under Washington and the Comte de Rochambeau, his messages became more specific. As if now renouncing the southern strategy, Clinton advised Cornwallis to find a defensible location where naval vessels could sail into Chesapeake Bay and remove his whole army for likely operations elsewhere, possibly against Philadelphia. The bustling community of Yorktown was Cornwallis’s choice, where in early August 1781 his troops began to construct an outer and an inner line of defensive works.

Even as Cornwallis’s army was digging in to protect against a possible landside assault, Washington and Rochambeau received an amazing message. In mid-August they learned from the Comte de Grasse, in command of a major French fleet, that he was sailing north from the West Indies with twenty-seven ships and 3,200 troops. His ships, sailors, and soldiers would be available, a least for a couple of months, for combined operations against British forces, possibly against New York City or elsewhere. Rochambeau convinced Washington that Cornwallis’s army was a more conquerable target than New York, especially if the French fleet blocked off the entrance to Chesapeake Bay, thereby denying the enemy force an escape route from Yorktown by sea.

Washington agreed, and the two commanders started marching their armies south, leaving behind just a token force to convince Clinton of their plan to attack New York City. However, Clinton soon learned that Washington and Rochambeau were on the move, and he arranged for a naval fleet under Admiral Sir Thomas Graves to sail quickly for Chesapeake Bay. The British vessels did not arrive in time, and a series of engagements with Grasse’s ships began on September 5 (the Battle of the Capes) that damaged both fleets, caused Graves to give up any attempted penetration into the bay. The British admiral sailed his wounded fleet back to New York.

Clinton, meanwhile, sent Cornwallis messages in early September warning that he soon would face Franco-American forces on the landside. At the same time, Clinton promised relief by sea, including possible troop reinforcements for Cornwallis, even though he had not yet learned about Graves’s naval failure. The expectation of relief caused Cornwallis to sit tight and hope for the best, rather than attempt to get away from Yorktown before the forces of Washington and Rochambeau appeared. With more than sixty artillery pieces and a double defensive line, Cornwallis convinced himself that his army could hold out until a British rescue fleet arrived. However, he warned Clinton in a message dated September 17 that he should expect to receive the worst possible news if relief did not occur soon.

A month later the worst had happened, at least from the British point of view. By the end of September Washington and Rochambeau had their armies in place before Yorktown. French land and naval forces totaled 7,800. Washington had 5,700 Continentals and 3,200 militia available to him, meaning that the allies had Cornwallis’s army outnumbered by a ratio of more than two to one. Worse yet, when Cornwallis received another misleading message from Clinton in late September that a relief fleet was on its way, along with 5,000 troops, he decided to abandon his outer defenses. He mistakenly assumed that he had to hang on for only a few more days.

The allies decided to use traditional siege tactics by digging parallel trenches from which they could safely bombard Yorktown. The unrelenting allied cannonade began on October 9 with thousands of cannonballs flying into the British lines for the next several days, not only causing mayhem and death but also obliterating portions of Yorktown. Almost as bad for Cornwallis, horrible diseases were spreading among his soldiers, including the highly contagious killer smallpox.

On October 15, not knowing that the promised relief force was yet to sail from New York, Cornwallis penned a message to Clinton that his army could not be saved. After the failed breakout attempt across the York River late on the evening of the 16th, Cornwallis, reckoning with possible annihilation of his force, sent out a lone drummer boy and an officer waving a white flag who carried a brief message asking for a cessation of hostilities and acceptable surrender terms.

That Cornwallis, the most aggressive of the ranking British generals, became sedentary and allowed himself to get ensnared at Yorktown might be described as ironic. Over and over again during the southern campaigns, he had bolted hither and thither, not following the dictates of the southern strategy but often wounding patriot forces while also wearing down his own. His decision to march into Virginia, looking for an all-out, climactic battle, was one aggressive move too many. Complying with vacillating instructions from his superior Clinton, he got himself stuck at Yorktown, even as he showed no dynamism to seize the few opportune moments available to extricate his force before it was too late.

What Cornwallis failed to appreciate was the prospect of combined Franco-American operations actually succeeding. For more than three years after the alliance came into being, American and French forces had not functioned together effectively. Then, somehow, everything came together for them at Yorktown, a thought that would bedevil Cornwallis for the rest of his life, even while he served in India and elsewhere in the British empire before his death in 1805. His legacy would be that of the general who allegedly lost America.

For the aristocrat general, the surrender ceremonies on the sunny autumn afternoon of October 19 were simply too personally humiliating. Cornwallis declared himself indisposed, and he sent out his second in command, Brigadier General Charles O’Hara, to lead his defeated column along a roadway past assembled French and American soldiers and sailors. Once at the surrender field, O’Hara looked for Rochambeau and offered him his sword, as if to say that the rebel force could not have prevailed without significant French assistance. Rochambeau pointed toward Washington, indicating that the victory belonged to the Americans. In turn, the patriot commander was not going to accept a sword from anyone of lower rank than Cornwallis, his defeated equal in command. He directed O’Hara to hand the sword to his second in command, General Benjamin Lincoln, who, as irony would have it, had suffered the indignity of surrendering his own sword to the British when they captured Charleston back in May 1780.

The scene on the afternoon of October 19 was cheerless for the British officers and soldiers who laid down their arms. Their drummers and fifers, with black ribbons attached to their instruments, played various tunes. Legend has persisted that one was the mournful melody "The World Turned Upside Down." Whether true or not, Yorktown turned the world upside down for the colonists’ former masters and, as such, represented a defining moment of triumph in the American experience. Yes, the war continued in the West Indies and other parts of the globe into 1783, but Yorktown set in motion a train of diplomatic events that resulted in Britain’s official recognition of American independence.

The southern strategy, a direct response to the Franco-American alliance, had failed; both Clinton and Cornwallis had failed; the French and the Americans had succeeded. In many ways O’Hara’s rude gesture of first seeking out Rochambeau had merit. The French did play an inestimable part in achieving American independence. At the same time, rebel persistence, as personified by George Washington and his long-term veteran Continentals, had kept the patriot cause intact until that day of surrender outside Yorktown—and even beyond. The result was a new republic bearing the name the United States of America, a nation with a grand destiny waiting to be realized.

James Kirby Martin is the Hugh Roy and Lillie Cranz Cullen University Professor of History at the University of Houston. His many books include Benedict Arnold: Revolutionary Hero: An American Warrior Reconsidered (1997); A Respectable Army: The Military Origins of the Republic, 1763–1789 (2nd edition, 2006, with Mark E. Lender); Forgotten Allies: The Oneida Indians and the American Revolution (2006, with Joseph T. Glatthaar); and a new edition of a classic wartime memoir of a young Continental soldier, Ordinary Courage: The Revolutionary War Adventures of Joseph Plumb Martin (2013).