On My Way to War in Iraq

by Maurice Decaul

The 1998 US embassy bombings in Kenya and Tanzania were followed by the 2000 bombing of the USS Cole, then of course September 11, 2001. Within two years I was on my way to Iraq.

The 1998 US embassy bombings in Kenya and Tanzania were followed by the 2000 bombing of the USS Cole, then of course September 11, 2001. Within two years I was on my way to Iraq.

I had met my recruiter six years earlier by happenstance. I was seventeen years old and sure of myself. I had mapped out my life. First, I would graduate from Brooklyn Tech, then go on to college. In college, I would apply for an NROTC scholarship. After college, I would seek a commission as a Marine Corps officer, preferably in the infantry.

Staff Sergeant Christopher Simmonds, my recruiter, had been a Marine for most of his life. He and I were very much alike. We were both immigrants from the Caribbean. We had both moved to the United States as a children and followed our dream of becoming Marines. He was a supply Marine in an infantry-centric Corps. He had once tried out for ANGLICO, the Marine Corps’ highly skilled parachute units known for their ability to direct air and naval gunfire onto enemy targets, but had injured his ankle during a jump and washed out.

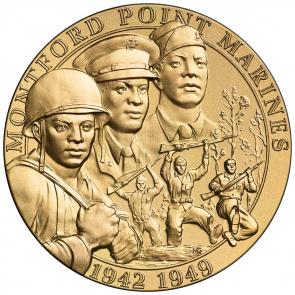

If we had lived during the Second World War, Marines like Staff Sergeant Simmonds and myself would have had to attend recruit training at Montford Point, North Carolina, a segregated facility established near Camp Lejeune in 1942 to train African American men to be US Marines.  We would have been in good company. During its seven years of operations, Montford Point trained 20,000 African American men to be US Marines. Those Marine Corps ancestors paved the way for young Marines like Simmonds to have the opportunity to attend a specialized school. Those same Marines made it possible for a Caribbean immigrant to imagine himself as a Marine Officer.

We would have been in good company. During its seven years of operations, Montford Point trained 20,000 African American men to be US Marines. Those Marine Corps ancestors paved the way for young Marines like Simmonds to have the opportunity to attend a specialized school. Those same Marines made it possible for a Caribbean immigrant to imagine himself as a Marine Officer.

Remarkably, during my many months of conversations with my recruiter, the Montford Point Marines were never discussed. Whether by oversight on his part or institutional amnesia on the part of the Marine Corps, the legacy of this first group of African American trailblazers was largely unaddressed during the time of my recruitment and subsequent enlistment.

Perhaps this has to do with the notion of all Marines being "green."

To head off any potential racial or ethnic conflicts, our drill instructors demanded we see each other as Marine recruits above all. We were told that we were all "green"—different shades of green, but green nevertheless. For the most part it worked, at least in boot camp. In the fleet, racism, colorism, and ethnocentrism would sometimes surface in the most bellicose ways: a Klan outfit thrown on during a party, a joke about someone’s Japanese or Jewish heritage, the Confederate battle flag on vehicles, epithets exchanged. At other times quieter discourse around race could occur, like when one of my junior Marines, a boy from Lower Alabama, told me that he grew up in a town in which blacks were still expected to step off the sidewalk for whites. He felt he needed to tell me so I would better understand how far he had come while serving in the Marines. We had just come back from exceptionally tough training in the Sierra Mountains, the type of environment in which even the toughest people will sometimes quit. We had been at altitude—10,000 feet for a few weeks—and his body had still not adjusted. On the hike down he nearly passed out, but I helped him. He wanted to thank me.

My parents were skeptical about the Marines. We had not come from a long line of military folk, though my cousin Al was serving in the navy and one of my father’s cousins had retired from the army after nearly thirty years. As long as I went to college first, my parents’ concerns would be placated, but my options for college were increasingly circumscribed due to mediocre grades, which meant that the Naval Academy was not an option.

I wasn’t sure how I would tell my mother that I had been meeting with a recruiter and that I was considering enlisting, but the discussion, when it happened, went smoother than I had expected. At seventeen, I signed a contract with the Marines, obligating myself to eight years of service, four years active and four years in the reserves.

A year later, I began recruit training at Paris Island. I was with my platoon learning how to fire the M16 when news of the bombing of the American embassies in Tanzania and Kenya reached us. We trained as if we would have to fight that night, but war came much later.

Orders to Iraq came right before the invasion kicked off. My unit was sufficiently ready, so we deployed months earlier than anticipated. When we arrived to Iraq, the war was well underway, and we fully expected to be thrown into the worst of the fighting, but for the most part we were not. Instead we took on the role of policing the city of Nasiriya.

Orders to Iraq came right before the invasion kicked off. My unit was sufficiently ready, so we deployed months earlier than anticipated. When we arrived to Iraq, the war was well underway, and we fully expected to be thrown into the worst of the fighting, but for the most part we were not. Instead we took on the role of policing the city of Nasiriya.

I had not given much thought to the notion of what role my own racial and ethnic identity might play in influencing my thoughts and actions in Iraq. I had been sufficiently indoctrinated to see Marines as Marines first, though on occasion one might be reminded of the complexities of race, history, war, and colonialism even in highly cooperative units with good discipline and esprit. It was a Vietnamese American Marine who forcefully reminded me of the role of African American service men and women in the Vietnam War. Simply put, he said, "my people beat your people." And I knew him to mean the Vietnamese struggle for independence and self-determination beginning with resistance to the French and Japanese, then later against people who looked like me representing the United States. He neglected to consider the African American struggle for full citizenship, for the basic right to exist—how even the opportunity to serve in war, and especially as a Marine, was a relatively new development.

I did ask him to define "my" people in relation to his people, but he digressed.

But he did make me think, and those few seconds stand out in my memory all these years later. By "your people," was he referring to people of African descent, or more specifically to people who claim allegiance to America irrespective of race, ethnicity, or color? I suspect he meant the latter, and if that is the case, I wonder whether the Iraqis with whom we interacted made distinctions between us, or simply saw us all as occupiers.

To the best of my knowledge, the Iraqis with whom we interacted saw us all as Americans. The one distinction I remember them making concerned the color of our undershirts. The Marines wear green and the army wears brown.

My family left St. Vincent in the mid-eighties for New York, but it was only a few years before that war had come to our part of the world when the United States military had invaded our neighbor, Grenada. Growing up, I sometimes imagined what it would have been like to wake up and find American Paratroopers and Marines when there were none in the village the day before. I imagined it to be a frightful sight, especially for a child. I also tried to imagine as an adult male whether I would resist or not, and sought to understand my answers.

Living in a rough New York neighborhood during the eighties and nineties, I knew the police kept the levels of violence down, but I also knew to keep a certain distance from men with weapons. I kept these thoughts in the back of my mind as I led my squad on missions. In Iraq, I made an effort to not call Iraqis by derogatory terms, lest I repeat the same kind of violence on Iraqis which too regularly in our own troubled history has been heaped on minority communities, including African Americans. I did my job, but wanted to ensure I respected Iraqi dignity.

Maurice Decaul, a former US Marine, is a poet, essayist, and playwright. His work has appeared in the New York Times, the Daily Beast, Sierra Magazine, Epiphany, Callaloo, Narrative, The Common, and others. His plays have been produced at theaters worldwide, from Harlem Stage in New York City to l’Odéon-Théâtre de l’Europe in Paris. His album, Holding it Down, a collaboration with Vijay Iyer and Mike Ladd, was named the LA Times Jazz Album of the Year in 2013.