Mutual Assistance: Building Black Community Life in Freedom

by Lois E. Horton

The Revolutionary War marked the beginning of slavery’s abolition in the North. Following the spirit of the Declaration of Independence, the 1777 Vermont and 1780 Massachusetts constitutions and the 1788 New Hampshire Declaration of Rights promised freedom and independence to people residing within their borders, though only Vermont’s brought immediate emancipation to enslaved people. In Massachusetts a series of suits, ending with Quock Walker’s 1783 success in the state supreme court, finally brought the legal recognition of Black freedom. Although slavery waned quickly in New Hampshire, African Americans’ status there was unclear until slavery was explicitly prohibited a few years before the Civil War. Other northern states passed gradual emancipation laws—Pennsylvania in 1780, Rhode Island and Connecticut in 1784, New York in 1799 (before granting immediate emancipation in 1827), and New Jersey in 1804—giving freedom only to those born to enslaved women after passage of the law but indenturing them until they became adults. (Those born before the law remained in slavery.) As the Revolution began, about forty-six thousand northerners were enslaved, and in 1790 more than forty thousand remained in slavery, while about twenty-seven thousand were free. By 1820, however, nearly eighty-five percent of Black people in the North were free.

As freedom came to Black Americans, many moved to cities, where they could reunite with family members, find employment, build organizations, and create communities. Some of the first organizations they formed for survival and sustenance were mutual aid societies and churches. The best-known societies in this period were the African Union Society in Newport, Rhode Island, the African Society in Boston, the African Humane Society in Philadelphia, and the African Society for Mutual Relief in New York City. That all of these organizations bear the title African reflects the fact that many members had been born in Africa, and most others were only a generation or two from their ancestral homelands.

The members’ cultural roots helped shape the values and practices of the societies. In African cultures, a proper burial was of central importance, and the groups generally began as burial societies. As the North gradually relinquished slavery, the emerging new communities were extraordinarily poor, and the need for support was great. Available resources were also limited by discrimination against Black people by many charitable organizations for the poor. In addition to assistance for burials, mutual aid societies also typically provided aid to the disabled; to widows and children of members, including orphaned children; and to ill members. They also offered unemployment insurance and employment assistance.

The first known Black mutual aid society was the African Union Society, formed in Newport, Rhode Island in 1780. Gradual emancipation had not yet begun in the state. But in addition to those already free, some African Americans had been promised freedom at war’s end in exchange for joining the 1st Rhode Island Regiment. Known as the Black Regiment, this Revolutionary unit included Narragansett Native American, enslaved, and free Black men. The African Union Society offered full memberships to free people and limited memberships to those still enslaved. Newport Gardner, an educated man who kept a record of births, deaths, marriages, and apprenticeships for Black Newporters, was one of the organization’s leaders, though he held a restricted membership. Born in West Africa in 1746, Gardner’s African name was Occramer Marycoo. When he was fourteen years old, he was transported to Rhode Island and sold by the ship’s captain to another captain, Calvin Gardner, who gave him his slave name.

Newport Gardner was educated along with his owner’s children and reportedly in four years learned English and French, studied singing and music composition, and converted to Christianity. He also composed the hymn “Promise Anthem,” said to be sung in the city’s churches until 1940. Gardner finally gained his freedom in 1791 at age forty-five, after he and friends won two thousand dollars in a lottery. His share allowed him to buy his own freedom and that of his wife, Limas, and to purchase or negotiate freedom for their eight children.

The following year the African Union Society granted Gardner full membership, and by the early 1800s, he had established his own singing and music composition school, had begun a free school for African American children, partly maintained by the Society, and had become an ordained deacon in the First Congregational Church. By that time, the society had become the African Benevolent Society with a female auxiliary. Like all the mutual aid societies, it often struggled to maintain the membership payments that supported its aid. To help provide proper funerals, it did nonetheless lend a bier and pall (cover) for members’ coffins, and in at least one instance in the late 1790s, gave a widow enough money to purchase tea, sugar, and rum for the many out-of-town guests expected for her husband’s funeral.

Other mutual aid societies that followed adopted similar aims and methods. In 1787 African Americans in Philadelphia, led by prominent Black ministers Richard Allen and Absalom Jones, formed the Free African Society, stressing charity, mutual aid, and leadership training. In 1796 forty-four Black men established Boston’s African Society, pledging to provide burial assistance, benefits to the needy, and aid for the ill and unemployed. This society also administered wills and, like most others, called on members to lead sober and moral lives. Other societies followed—Philadelphia’s African Humane Society in the 1790s and New York City’s African Society for Mutual Relief in 1808. In Philadelphia alone, there were nearly fifty societies in 1830 and one hundred by 1838. Most organizations were open to a general membership, some were either for men or for women, and a few were specialized, such as New York’s African Marine Fund organized by sailors.

Other mutual aid societies that followed adopted similar aims and methods. In 1787 African Americans in Philadelphia, led by prominent Black ministers Richard Allen and Absalom Jones, formed the Free African Society, stressing charity, mutual aid, and leadership training. In 1796 forty-four Black men established Boston’s African Society, pledging to provide burial assistance, benefits to the needy, and aid for the ill and unemployed. This society also administered wills and, like most others, called on members to lead sober and moral lives. Other societies followed—Philadelphia’s African Humane Society in the 1790s and New York City’s African Society for Mutual Relief in 1808. In Philadelphia alone, there were nearly fifty societies in 1830 and one hundred by 1838. Most organizations were open to a general membership, some were either for men or for women, and a few were specialized, such as New York’s African Marine Fund organized by sailors.

It is remarkable how many mutual aid societies grew in such poor communities. The societies had initiation fees for members that ranged from 25 cents to one dollar, and monthly dues ranging from 12½ cents to 50 cents. This was substantial, considering that in New England in 1808 the average female domestic worker earned 70 cents a week. In Massachusetts in 1800 a day laborer earned 30 to 60 cents a day and in 1810 from 50 cents to one dollar a day. Such day labor provided insecure wages, and much of the work in port cities was seasonal. Additionally, many workers were seamen, often away from home for months or years at a time. Special arrangements for monthly dues were made for these men who were generally paid at the end of a voyage. Yet these societies did manage to provide food, clothing, firewood, and other goods and services to needy members. The Free African Society of Philadelphia, for example, provided total annual benefits of $6,000 in 1830, $9,000 in 1836, and $14,000 in 1838.

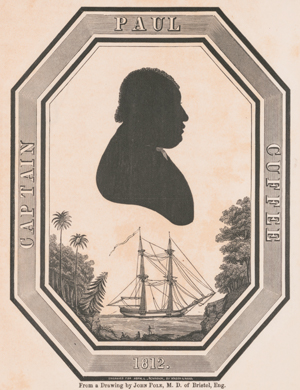

Like other organizations, mutual aid societies required respectable and law-abiding behavior for members as a way they could prove African American suitability for American citizenship. However, many African-born Americans expressed their desire to emigrate to Africa. During the 1790s and early 1800s members of the societies in Newport, Providence, Boston, and Philadelphia carried on a correspondence promoting the possibility. Newport Gardner encouraged emigration plans by Paul Cuffe, a Massachusetts African American Quaker sea captain, and in early 1816 Cuffe successfully transported thirty-four Black American settlers to the British colony of Sierra Leone. Finally, in early 1826, nearly ten years after Cuffe’s death, eighty-year-old Newport Gardner and a fellow society member, seventy-year-old Salmar Nubia, were two of at least thirty-two African American emigrants who landed in Liberia, a colony sponsored by the American Colonization Society. Both Gardner and Nubia died a few months after their arrival in Africa.

Like other organizations, mutual aid societies required respectable and law-abiding behavior for members as a way they could prove African American suitability for American citizenship. However, many African-born Americans expressed their desire to emigrate to Africa. During the 1790s and early 1800s members of the societies in Newport, Providence, Boston, and Philadelphia carried on a correspondence promoting the possibility. Newport Gardner encouraged emigration plans by Paul Cuffe, a Massachusetts African American Quaker sea captain, and in early 1816 Cuffe successfully transported thirty-four Black American settlers to the British colony of Sierra Leone. Finally, in early 1826, nearly ten years after Cuffe’s death, eighty-year-old Newport Gardner and a fellow society member, seventy-year-old Salmar Nubia, were two of at least thirty-two African American emigrants who landed in Liberia, a colony sponsored by the American Colonization Society. Both Gardner and Nubia died a few months after their arrival in Africa.

Concerned for members’ moral and spiritual well-being, mutual aid societies were very often the seeds of Black churches and schools for African American children. Like most community organizations, they worked for the abolition of slavery. They created networks linking urban Black communities in anti-slavery work and providing information about education and employment. Mutual aid societies compensated for some of the discrimination Black Americans faced, expressed the values of members’ cultural heritage, and answered the needs of their communities.

Bibliography

Robert L. Harris, Jr., “Early Black Benevolent Societies, 1780–1830,” The Massachusetts Review 20, 3 (Autumn 1979): 603–625.

James Oliver Horton and Lois E. Horton, Black Bostonians, rev. ed. (New York: Holmes & Meier, 1999).

James Oliver Horton and Lois E. Horton, In Hope of Liberty (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997).

Laws of the African Society, Instituted at Boston, Anno Domini 1796 (Boston: Printed for the Society, 1802), in Dorothy Porter, Early Negro Writing, 1760–1837 (Boston: Beacon Press, 1971), 9–12.

Lois E. Horton is professor of history emerita at George Mason University. With James Oliver Horton she has written and edited numerous books, including Slavery and Public History: The Tough Stuff of American Memory (The New Press, 2006), Slavery and the Making of America (Oxford University Press, 2004), Hard Road to Freedom: The Story of African America (Rutgers University Press, 2001), and In Hope of Liberty: Culture, Community and Protest among Northern Free Blacks, 1700–1860 (Oxford University Press, 1997).