Medical Advances in Nineteenth-Century America

by Bert Hansen

We live in an age when there seems to be a medical breakthrough in the headlines every few days, when new discoveries are immediately—and sometimes prematurely—put into practice. It is easy for us, therefore, to assume that this same enthusiasm for novelty characterized medicine in the past as well. But that is not what history shows.

We live in an age when there seems to be a medical breakthrough in the headlines every few days, when new discoveries are immediately—and sometimes prematurely—put into practice. It is easy for us, therefore, to assume that this same enthusiasm for novelty characterized medicine in the past as well. But that is not what history shows.

Medicine became recognizably "modern" in the nineteenth century, producing new inventions, new theories, new curative powers, and a rebirth of professionalism (for both doctors and nurses). Scientific developments played a role in all these changes, gradually replacing the trial-and-error inventiveness that had long characterized medical practice.

By a quirk of history, we can even pick a symbolic birthday for modern medicine, October 16, 1846—the date of the first publicly reported use of ether for surgical anesthesia. This particular discovery was also America’s first major contribution to international medical practice. The path-breaking operation took place in Boston’s Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH). Following the custom of the time, surgical suites and surgical amphitheaters for student observation were located on a hospital’s uppermost floor to maximize natural illumination. At MGH, that attic room is still called The Ether Dome. On this red-letter day, Harvard Professor of Surgery John Collins Warren removed a tumor on the jaw for a patient named Gilbert Abbot as the first test of a new inhaled anesthetic invented and administered by a dentist named William Thomas Green Morton. Many of those watching the operation were skeptical since earlier experiments at MGH had faltered and because no solution had been found in thousands of years. When Dr. Warren finished his work without any screaming or thrashing from his patient, he is said to have announced to those in attendance, "Gentlemen, this is no humbug." (Fenster 2001; Wolfe 1993).

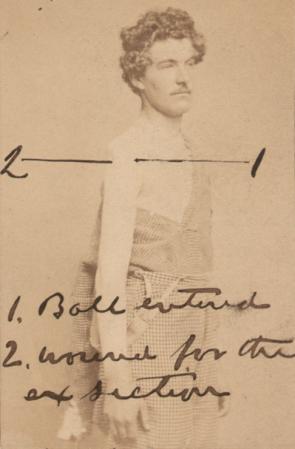

Before this date, physicians had repeatedly tried and failed to find an adequate means to instill a temporary suspension of pain. Without any way to control pain, most surgery simply could not be undertaken. Even if physicians proved willing to inflict horrible pain, a patient writhing from it could not be held still enough for the surgeon’s scalpel to do its delicate work. Surgery had thus been limited to a few types of procedures: cataract removal, extirpation of superficial growths on the skin, and amputation of a badly damaged limb (such as a foot crushed by a wagon wheel or an arm blasted apart by a bullet).

Amputation, often on the battlefield, did save lives, since a crushed foot or arm would almost always lead to a fatal systemic infection. Working very quickly, a skillful surgeon could cut through the flesh, saw completely through the bone, and apply a red hot iron to cauterize the stump’s raw surface and stop the bleeding—sometimes performing the entire operation in less than two minutes. The amputation of a limb carried a mortality risk of about fifty percent—a depressing figure, to be sure. But even a fifty-fifty chance of survival was a fair gain over an almost certain death without such treatment.

The ability to banish pain during surgery (though not during the recovery period) was a medical breakthrough of the highest order and a landmark eminently visible in retrospect. But to gain a more complete picture of the historical significance of a medical innovation, we must understand not only who discovered it and how it worked, but also, and perhaps more importantly, who used it, how quickly and how widely it became known, and what further changes it made possible.

For example, the world barely took notice of ether surgery in 1846. There was no medical revolution. There were no headlines. Even over several years, only a handful of newspaper reports appeared. The public image of the doctor did not change. There was no wholesale adoption of this technique by the medical profession despite reports published in medical journals and the occasional use of ether by other surgeons. Surgeons used it or avoided it in individuals cases for a variety of reasons, including notions of which patients (by ethnicity or gender or social class) would be more sensitive to pain and thus more in need of the anodyne (Pernick, 1985). Although the use of ether ultimately triumphed, its acceptance was slow and uneven for several decades.

For us today, a large oil painting of the first American operation using ether and a few daguerreotype photographs of early operations are fascinating historical images. (Wolfe 1993; Lowry and Lowry 2005). But the impression they create—that is, that the public immediately recognized ether surgery as a momentous breakthrough—is false. All the early photographs were posed re-enactments taken after the fact; and none of them was published at the time.

References Cited

Fenster, Julie M. (2001). Ether Day: The Strange Tale of America’s Greatest Medical Discovery and the Haunted Men Who Made It (HarperCollins Publishers, 2001)

Hansen, Bert (1998). "America’s First Medical Breakthrough: How Popular Excitement about a French Rabies Cure in 1885 Raised New Expectations of Medical Progress," American Historical Review 103:2 (April 1998), 373–418.

Hansen, Bert (1999). "New Images of a New Medicine: Visual Evidence for Widespread Popularity of Therapeutic Discoveries in America after 1885," Bulletin of the History of Medicine 73:4 (December 1999), 629–678.

Howell, Joel D. (1995). Technology in the Hospital: Transforming Patient Care in the Early Twentieth Century (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995).

Lowry, Bates, and Isabel Lowry (2005). "Simultaneous Developments: Documentary Photography and Painless Surgery," a chapter in Grant B. Romer and Brian Wallis, Young America: The Daguerreotypes of Southworth and Hawes (New York: International Center of Photography, 2005).

Pernick, Martin S. (1985). A Calculus of Suffering: Pain, Professionalism, and Anesthesia in Nineteenth-Century America (Columbia University Press, 1985).

Wolfe, Richard J. (1993). Robert C. Hinckley and the Recreation of the First Operation under Ether (Boston: Boston Medical Library in the Frances A. Countway Library of Medicine, 1993).

Bert Hansen is a professor of history at Baruch College, The City University of New York, and author of Picturing Medical Progress from Pasteur to Polio (2009).