Lockean Liberalism and the American Revolution

by Isaac Kramnick

The town of Boston took an important step toward rebellion on November 20, 1772, by adopting a declaration of "the Rights of the Colonists" drafted by Sam Adams, the firebrand of the Revolution. Adams summarized these "Natural rights" as "First, a Right to LIFE; Secondly to LIBERTY; thirdly to Property." He described a "natural liberty of Men," a "state of nature" where each was "sole judge of his own rights and the injuries done him." This free man entered into political society by agreeing to accept an "Arbiter or indifferent Judge between him and his neighbors," a civil government that would support, defend, and protect his natural rights to "life, liberty and property." In 1772 the rights that Adams described were being threatened by British imperial policy. An honest man, Adams acknowledged in his declaration that the source of these principles was the English political theorist "Mr. Lock" whose ideas on politics had been "proved beyond the possibility of contradiction on any solid ground."

The town of Boston took an important step toward rebellion on November 20, 1772, by adopting a declaration of "the Rights of the Colonists" drafted by Sam Adams, the firebrand of the Revolution. Adams summarized these "Natural rights" as "First, a Right to LIFE; Secondly to LIBERTY; thirdly to Property." He described a "natural liberty of Men," a "state of nature" where each was "sole judge of his own rights and the injuries done him." This free man entered into political society by agreeing to accept an "Arbiter or indifferent Judge between him and his neighbors," a civil government that would support, defend, and protect his natural rights to "life, liberty and property." In 1772 the rights that Adams described were being threatened by British imperial policy. An honest man, Adams acknowledged in his declaration that the source of these principles was the English political theorist "Mr. Lock" whose ideas on politics had been "proved beyond the possibility of contradiction on any solid ground."

Meanwhile, the leading colonial critic of the drift to rebellion, the Anglican clergyman Jonathan Boucher, preached to his congregants in Virginia and Maryland that they had an obligation as Christians to accept, indeed to "reverence authority," since "there is no power, but of God; the powers that be are ordained of God." There was never, he added, a time when "the whole human race is born equal" when "no man is naturally inferior, or, in any respect, subjected to another." Governments were not the product of voluntary consent, he insisted, but were given by God to men who were then forever subordinate to those superiors God had set to govern them. He ridiculed notions of a "social compact" and of "a right to resistance." In a 1774 sermon defending the divine right of kings to govern against colonial claims of self-government Boucher singled out the evil source of the misguided views of the rebellious colonists: "Mr. Locke" was the author "of the system now under consideration." Americans, he hoped, would choose obedience to monarchs as announced in the New Testament’s "Romans 13" over the "right to resistance, for which Mr. Locke contends."

Boucher was the leading spokesman in the Revolutionary era for the ideals and values of the Christian commonwealth, the long-dominant paradigm of politics in the West, with its roots in the writings of St. Paul, Augustine, Aquinas, Calvin, and the American Puritans like John Winthrop. This traditional Christian view of the state, which the American revolutionaries would reject, fused religion and politics by making the state part of God’s design to redeem humanity. It saw the state’s purpose as the execution of God’s moral laws, the protection of God’s faithful, and the furthering of God’s truth. God had given his creatures a revealed law through scripture, a set of absolute and timeless principles of right and wrong, and enjoined His creatures to live lives of virtue and morality. The state’s mission, then, was to implement this godly order in a particular time and place. Its laws were to proclaim God’s truths and to reward the virtuous life, while punishing sin and immorality. Those who presided over the state—traditionally monarchs, lords, and magistrates—were God’s servants, His agents in the time-bound realm for the realization of God’s moral mission. The Christian commonwealth, be it the Catholic realm for Aquinas or the Protestant realm for an eighteenth-century Anglican cleric like Boucher, thus imagined religion and politics as forever bound to each other.

Against this traditional ideal of the Christian commonwealth there arose in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century England an alternative model of the relation of church and state, one that self-consciously separated the two realms and spoke of the state as purely secular in its origins, functions, and purpose. The American Founders accepted this new ideal and rejected a politics where a state church proclaimed the moral necessity of deference and subordination to political rulers, and where Christian magistrates ensured that proper religious observance was enforced and sinners punished by the secular sword in the quest to achieve a Christian society.

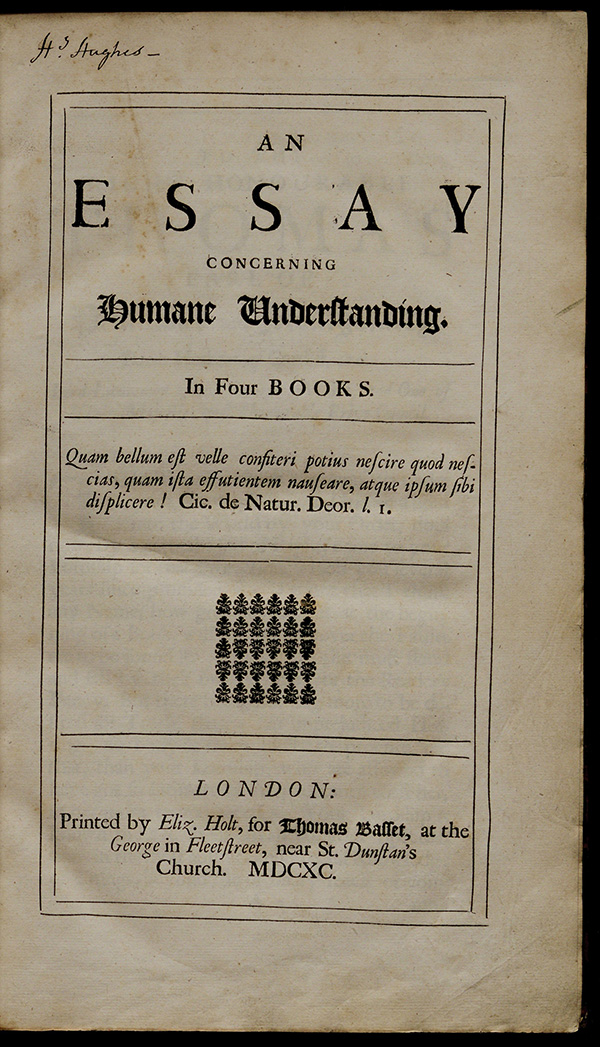

The most influential and persuasive proponent of this radically new way of viewing the state was John Locke, as both Sam Adams and the Reverend Boucher made clear. Locke (1632–1704) was the English philosopher whose writings most shaped the intellectual and political world view of Americans in the eighteenth century. Indeed, his anti-statist views and his preoccupation with the sanctity of private property have continued to influence the fundamental beliefs of Americans to this day. All the important figures of the revolutionary generation, including John Otis, John and Sam Adams, James Madison, Thomas Jefferson, Patrick Henry, and Benjamin Franklin, were disciples of Locke. His writings shaped sermons in Revolutionary pulpits and editorials in Revolutionary newspapers. The Declaration of Independence, in fact, reads like a paraphrase of Locke’s influential Second Treatise of Civil Government.

For Locke, writing in the 1670s and 1680s, the state’s origin was not shrouded in the impenetrable mystery of divine gift or dispensation. The source of "the powers that be," the magistrates and monarchs that governed, was the people, who voluntarily contracted to set up governments in order to protect their natural rights to life, liberty, and property. In Locke’s writings we witness the birth of liberal social theory, which posits the autonomous independent individual as the center of the social universe, for whom social and political institutions are self-willed constructs whose purpose and function are to secure the rights and interests of self-seeking individuals.

In liberal Lockean social theory the function of government is negative. It is willed into being by individual men to serve merely as an umpire in the competitive scramble for wealth and property. Government only protects life, liberty, and property. It keeps peace and order in a voluntaristic, individualistic society. In Locke’s writings government no longer seeks to promote the good or moral life. No longer does government nurture and educate its subjects in the ways of virtue, or preside over the betterment or improvement of men and society. No longer does government defend and propogate moral and religious truths. These former noble purposes of the classical and Christian state are undermined as liberal theory assigns the state the very mundane and practical role of protecting private rights, especially property rights. Two thousand years of thinking about politics in the West is overturned in Locke’s writings, as the liberal state repudiates the classical and Christian vision of politics.

The Lockean state is seen as simply the servant or agent of the propertied men who contract to set it up, their interest in creating the state no more than the very worldly one of having it protect their lives, liberty, and property. The state, according to Locke, should do no more, nor no less. If it did more, such as prescribing religious truth, or if it did less, such as failing to protect the liberty or property of its subjects, then as a mere servant the state would be dismissed by those who had set it up and would be replaced by another. Such, indeed, was the political ideology of the Founding Fathers as captured by Jefferson in the Declaration of Independence. The language is pure Locke.

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights; that among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of happiness: That to secure these rights Governments are instituted among men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed; that whenever any form of government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the right of the people to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its power in such form as to them shall seem most likely to effect their safety and happiness.

Since the liberal vision of the state assumed that government does nothing but perform the strictly limited task of protecting rights, liberal theory self-consciously strips government and the state of any moral or religious function. Once again it was the Englishman John Locke who provided the principal expression of this new liberal world view for the founders in his Letter Concerning Toleration. In the Letter, Locke sought, as he put it, "to distinguish exactly the business of civil government from that of religion, and to settle the just bounds that lie between one and the other." He did this by making clear what the state does. The state, he wrote,

seems to me to be a society of men constituted only for the procuring, preserving, and advancing their own civil interests. Civil interests I call life, liberty, health, and indolence of body; and the possession of outward things, such as money, lands, houses, furniture, and the like. It is the duty of the civil magistrate, by the impartial execution of equal laws, to secure unto all the people in general, and to every one of his subjects in particular the just possession of these things belonging to this life.

Men, according to Locke, have contracted to obey civil authority not in order for that authority to tell them what to believe or how to pray but simply because it keeps the peace. As for changing or influencing what people believe, Locke writes,

Every man has commission to admonish, exhort, convince another of error, and, by reasoning, to draw him into truth; but to give laws, receive obedience, and compel with the sword, belongs to none but the magistrate. And upon this ground, I affirm that the magistrate’s power extends not to the establishing of any articles of faith, or form of worship, by the force of his laws.

In this crucial turning point in Western culture liberal ideology, very much influenced by Protestant conviction, pushes morality and religion outside the public political realm to a private realm of individual experience, transforming the entire definition of what is public and what is private. The public realm, which for nearly two millennia was all-inclusive, supervising in the name of the Christian commonwealth political, economic, and religious matters, is severely curtailed as liberal theory expands the role of the private realm, giving it morality, religious belief, and soon economic activity. What a revolution seventeenth- and eighteenth-century English liberalism brings in insisting that matters of religious conviction are not public and political matters but private and personal ones. As Locke notes,

Any one may employ as many exhortations and arguments as he pleases, toward the the promoting of another man’s salvation. But all force and compulsion are to be forborne. Nothing is to be done imperiously. Nobody is obliged in that matter to yield obedience unto the admonitions or injunctions of another, further than he himself is persuaded. Every man in that has the supreme and absolute authority of judging for himself. And the reason is because nobody else is concerned in it, nor can receive any prejudice from his conduct therein.

Equally profound in this liberal revolution that would so influence America’s founding generation was the change in the understanding of what law was and what purpose it served. Pushed aside was the Christian conception of law as a worldly injunction requiring virtuous and moral living, ultimately traceable to God’s own standards of right and wrong. For Locke and for the liberals who founded America "laws provide simply that the goods and health of subjects be not injured by the fraud and the violence of others." Locke adds, "The business of the law is not to provide for the truth of opinion, but for the safety and security of the commonwealth and of every particular man’s goods and persons. The truth is not taught by law, nor has she any need of force to procure her entrance into the minds of men."

The Revolutionary founders of America created a government indifferent to guarding and promoting moral or religious truth. Politics, as they saw it, was not designed to shape virtuous character through religion. They rejected the central premise of Boucher’s Christian commonwealth and in its stead created a secular state, where individuals pursued happiness as they personally conceived it, free of state tutelage and interference. Religion was a vital matter, but it was a matter of individual conscience, outside the state’s concern and competence.

The Constitution would not mention God. The new American state would not serve the glory of Christianity; it would merely preside over the commercial republic, an individualistic and competitive America preoccupied with private rights and personal autonomy. Locke, in his Second Treatise, had described the state as nothing more than an "impartial judge" or "umpire," a neutral arbiter among the competing private interests of civil society. James Madison shared this secular vision of the state. In his famous Federalist No. 10 he outlined the clashing commercial groups in America: creditors, debtors, farmers, manufacturers, merchants, and financiers. The state’s purpose, he wrote, was "the regulation of these various and interfering interests," not proclaiming God’s truths or rewarding a virtuous, godly life. In a letter to George Washington, Madison actually described the state as being no more than a "disinterested and dispassionate umpire in disputes." Dead and buried are the lofty ambitions of the Christian state.

Among America’s founders, no one better captured this spirit of Lockean liberalism than Thomas Jefferson. The basic Lockean theory of freedom and the minimal state is expressed in beautiful American language by Jefferson in the one book he wrote, Notes on the State of Virginia, where he explains why the state must remain unconcerned with private religious belief or even disbelief.

The legitimate powers of government extend to such acts only as are injurious to others. But it does me no injury for my neighbor to say There are twenty gods, or no God. It neither breaks my leg, nor picks my pocket.

The lineage is direct. The words are strikingly similar. Locke wrote that secular laws were intended only to provide that "the goods and health of subjects be not injured." He insisted that "if a Roman Catholic believes that to be really the body of Christ, which another man calls bread, he does no injury thereby to his neighbors." Lockean liberalism, which so influenced the revolutionary inventors of the American state, saw politics not about salvation, or about doctrinal purity and truth, not even about men leading virtuous and moral lives. Politics was about personal rights, and focused on economics and property; the state’s job was merely to be an umpire ensuring a peaceful and secure enjoyment of personal rights safe from injury. The state’s concern was making certain that no one’s leg was broken or purse stolen. The founders of America like Sam Adams rejected Boucher’s Christian commonwealth and in so doing made "Mr. Lock" and his radical liberalism the American creed.

Isaac Kramnick is the Richard J. Schwartz Professor of Government at Cornell University. He is the author of several books, including Bolingbroke and His Circle: the Politics of Nostalgia in the Age of Walpole (1992) and The Rage of Edmund Burke Portrait of an Ambivalent Conservative (1977), and numerous articles on eighteenth-century topics.