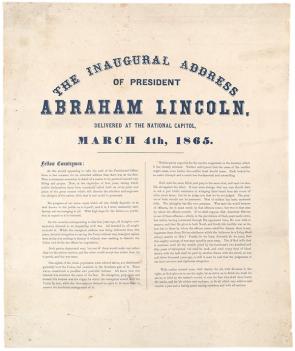

Lincoln’s Second Inaugural

by Lewis E. Lehrman

Abraham Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address was a peerless work of political theology, evoked in the native tongue he had mastered in the same diligent way he had mastered the rebellion. In 703 words, he summarized the moral dilemma of slavery in American history and the four-year conflict it caused. In a few words, he looked back at America’s original sin as he looked forward to the Union’s restoration. With the sword of a poet, the commander in chief had, in a few exquisite words, summoned the "better angels" of our nature, now set free by the Thirteenth Amendment and the abolition of slavery. "Neither party" to the Civil War, Mr. Lincoln observed, "expected for the war, the magnitude, or the duration, which it has already attained. Neither anticipated that the cause of the conflict might cease with, or even before, the conflict itself should cease. Each looked for an easier triumph, and a result less fundamental and astounding."[1] There was to be no easy triumph, but there arose great expectations at the moment of Lincoln’s Second Inaugural—as the Civil War came to an end.

Abraham Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address was a peerless work of political theology, evoked in the native tongue he had mastered in the same diligent way he had mastered the rebellion. In 703 words, he summarized the moral dilemma of slavery in American history and the four-year conflict it caused. In a few words, he looked back at America’s original sin as he looked forward to the Union’s restoration. With the sword of a poet, the commander in chief had, in a few exquisite words, summoned the "better angels" of our nature, now set free by the Thirteenth Amendment and the abolition of slavery. "Neither party" to the Civil War, Mr. Lincoln observed, "expected for the war, the magnitude, or the duration, which it has already attained. Neither anticipated that the cause of the conflict might cease with, or even before, the conflict itself should cease. Each looked for an easier triumph, and a result less fundamental and astounding."[1] There was to be no easy triumph, but there arose great expectations at the moment of Lincoln’s Second Inaugural—as the Civil War came to an end.

"When Mr. Lincoln delivered his second inaugural address, I had the privilege of standing within twenty feet of him," recalled an Army corporal in the presidential guard:

His voice was singularly clear and penetrating. It had a sort of metallic ring. His enunciation was perfect. There was an immense crowd of people surrounding the east front of the Capitol, but it seemed as if his voice would reach the entire audience. It had rained a great deal during the forenoon, and clouds overcast the sky as the presidential party and the Senate came out on the east portico. While the ceremonies were in progress the clouds suddenly parted, and, although it was about midday, Venus was seen clearly shining in the blue sky. The attention of the immense throng was directed to it.[2]

The entire nation was moved then, as it is now, by the gravity of the moment, the eloquence of the President.

The speech focused on the great issues of Lincoln’s presidency—the war, the preservation of the Union, and the emancipation of black slaves. It was in the courtroom that the onetime Illinois litigator had mastered the language and argument whereby he learned to persuade such an audience. But Lincoln had often warned against rhetorical excess. He himself had learned to take care not to inflame passion. "In times like the present, men should utter nothing for which they would not willingly be responsible through time and in eternity," Lincoln declared in his Second Annual Message to Congress in December 1862.[3] Now, with the dome of the Capitol looming behind him—rebuilt during the Civil War—the President emphasized that "[t]he progress of our arms, upon which all else chiefly depends, is as well known to the public as to myself. . . . With high hope for the future, no prediction in regard to it is ventured."[4] Lincoln would not raise expectations for a quick conclusion of the war. But he was never self-conscious about the decisive role of the Union Army.

In the face of arguments that there were other philosophical, constitutional, and economic causes for war and secession, the President unequivocally identified slavery as the cause of the Civil War. With slavery abolished, there were grounds for cautious hope at the onset of his second presidential term: "Fondly do we hope—fervently do we pray—that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away." This he said as his future assassin, John Wilkes Booth, lurked nearby. "Yet, if God wills that it continue, until all the wealth piled by the bond-man’s two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash, shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said ‘the judgments of the Lord, are true and righteous altogether." Lincoln scholar Lucas Morel remarked: "Given the aim of the speech, which is essentially the aim of his second term as president—namely, uniting a divided country—Lincoln had to hide or diminish the culpability of the South for the Civil War but he could not ignore it."[5] Indeed, the President spoke plainly: "All knew that [slavery] was, somehow, the cause of the war." The entire speech was the work of a disciplined master of the English language. Moreover, Lincoln had developed the exacting habit to edit the words he expected to be printed, read, and interpreted. It is fair to say that in many cases he wrote for all future time.

The enduring power of Lincoln’s Second Inaugural originated in the unique combination of five salient strengths of the President. First, Lincoln possessed a phenomenal memory for facts, people, and phrases and the genius to mobilize them with the pen. Second, Lincoln had assiduously studied the history of the United States, often in the primary documents themselves. The great Peoria and Cooper Union speeches are but two examples of his primary historical research. Mindful of America’s history, he tended from his earliest political days to concentrate on the republican example America must set for other nations. Third, he read, wrote, and loved great prose and poetry with a deep respect for the compelling rhythms of the Bible and Shakespeare. Fourth, he was a lifelong student of leadership. He understood—he had learned from hard experience—how to distill leadership lessons and to express them in compelling words and stories often drawn from both biblical and literary lessons. Finally, commingled with his brooding melancholy, Lincoln’s was a spiritual temperament. Before and after he was elected President he felt the hand of Providence intervening in his country’s history, even perhaps in his decisions. As the great man said: "The will of God prevails—In great contests each party claims to act in accordance with the will of God. Both may be, and one must be wrong. God can not be for, and against the same thing at the same time. In the present civil war it is quite possible that God’s purpose is something different from the purpose of either party—and yet the human instrumentalities, working just as they do, are of the best adaptation to effect His purpose."[6]

One can hear biblical tones in his musings, his formal writings, his speeches. As Professor Morel noted: "From his 1838 Lyceum Address to his 1865 Second Inaugural Address, Lincoln quoted or alluded to the Bible with a familiarity and profundity that rivaled the preachers of his day."[7] However, in no writing before the Second Inaugural did Lincoln use scriptural language and its cadences to such extraordinary effect. Lincoln’s faith has often been identified with the Old Testament. Theologian Reinhold Niehbuhr noted: "Lincoln’s faith is closely akin to that of the Hebrew prophets, who first conceived the idea of a meaningful history. If there was an element of skepticism in his grand concept, one can only observe that Scripture itself, particularly the Book of Job, expresses some doubts about giving the providential aspects of history exact meanings in neat moral terms."[8] Though no orthodox believer, Lincoln thought to align his actions with the will of Providence, not unlike some prophets of the Old Testament. But he also quoted Jesus of the New Testament, perhaps to encourage his anti-slavery cohorts: "Be ye perfect as your father in heaven is perfect." Lincoln’s disposition was not quick to judgment, as he made clear in his Second Inaugural: "It may seem strange that any men should dare to ask a just God’s assistance in wringing their bread from the sweat of other men’s faces, but let us judge not, that we be not judged."

But divine judgment is final. As historian James L. Huston wrote: "The middle portion of the Second Inaugural . . . is almost abolitionist in its condemnation of the peculiar institution. Here, in the most religious portion of the speech, Lincoln declared that some force, which he could only describe as a ‘living God,’ had determined slavery was to end."[9] Lincoln understood that a president speaks to many diffeent audiences—in his particular case, to free soil supporters in the North as well as to secessionists and slaveholders in the South. As pastor to the Union, he preached the equality of the Declaration of Independence, but with a humility often absent in didactic presidents and politicians. He understood he was speaking for posterity. Lincoln biographer Michael Burlingame noted, "Readers in Old as well as New England were appreciative. The Duke of Argyll told Charles Sumner: ‘It was a noble speech, just and true, and solemn. I think it has produced a great effect in England.’"[10]

There may be no peroration the equal of Lincoln’s Second Inaugural in any language: "With malice toward none; with charity for all; with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in; to bind up the nation’s wounds; to care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow, and his orphan—to do all which may achieve and cherish a just, and a lasting peace, among ourselves, and with all nations." As the great black abolitionist Frederick Douglass told President Lincoln later that day at a White House reception, it was "a sacred effort."[11] Lincoln himself was modest but honest. He responded to the praise of a New York editor: "Every one likes a compliment. Thank you for yours . . . on the recent inaugural address. I expect the latter to wear as well as—perhaps better than—anything I have produced."[12]

[1] Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, ed. Roy P. Basler et al. (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1953–1955), 8:332-333.

[2] Robert W. McBride, Lincoln’s Body Guard, the Union Light Guard of Ohio: With Some Personal Recollections of Abraham Lincoln (Indianapolis: Edward J. Hecker, 1911), 29–30.

[3] Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, 5:535.

[4] Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, 8:332.

[5] Lucas E. Morel, "Lincoln’s Political Religion and Religious Politics," in John Y. Simon, Harold Holzer, and Dawn Vogel, eds., Lincoln Revisited (New York: Fordham University Press, 2007), 30.

[6] "Meditation on the Divine Will," [September 2, 1862?], in Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, 5:403-404

[7] Morel, 21.

[8] Reinhold Niebuhr, "The Religion of Abraham Lincoln" in Kenneth L. Deutsch and Joseph R. Fornieri, Lincoln’s American Dream: Clashing Political Perspectives (Washington, DC: Potomac Books, 2005), 379.

[9] James L. Huston, "The Lost Cause of the North," Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association (Winter 2012): 36.

[10] Michael Burlingame, Abraham Lincoln: A Life (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008), 2:772.

[11] Frederick Douglass, The Life and Times of Frederick Douglass: From 1817–1882, ed. John Lobb (London: Christian Age Office, 1882), 321.

[12] Abraham Lincoln to Thurlow Weed, March 15, 1865, in Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, 8:356.

Lewis E. Lehrman is co-founder of the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History and the author of Lincoln at Peoria (2008).