Joshua Johnson: Portraitist of Federal-Era Baltimore

by Daniel Fulco

When African American portrait painter and formerly enslaved man Joshua Johnson (ca. 1763–ca. 1824) began his career during the 1790s, Baltimore was growing rapidly and developing into an economically prosperous, mercantile city of the Upper South.[1] In his first newspaper advertisement, Johnson, one of America’s first professional Black artists, asserted his successes and abilities while acknowledging the generous support of his patrons:

When African American portrait painter and formerly enslaved man Joshua Johnson (ca. 1763–ca. 1824) began his career during the 1790s, Baltimore was growing rapidly and developing into an economically prosperous, mercantile city of the Upper South.[1] In his first newspaper advertisement, Johnson, one of America’s first professional Black artists, asserted his successes and abilities while acknowledging the generous support of his patrons:

The subscriber, grateful for the liberal encouragement which an indulgent public have conferred on him in his first essays in PORTRAIT PAINTING, returns his sincere acknowledgments. He takes liberty to observe, That by dint of industrious application, he has so far improved and matured his talents, that he can insure the most precise and natural likenesses . . .[2]

With assurance and strategic self-promotion, the painter referred to himself as follows:

A self-taught genius, deriving from nature and industry in his knowledge of the Art; and having experienced many insuperable obstacles in the pursuit of his studies, it is highly gratifying to him to make assurances of his ability to execute all commands, with an effect, and in a style which must give satisfaction . . .[3]

Johnson’s use of the words “self-taught genius” conveys that he primarily learned to paint on his own while the “insuperable obstacles” refer to the many racial and social hurdles that he faced in pursuing his profession. As a freeman working in the slave state of Maryland, the artist no doubt faced discrimination; his bi-racial identity and the fact that he identified as Black would have likely prevented him from pursuing a course of formal art instruction in a White school or academy in Baltimore. [4] Nevertheless, he overcame many of these difficulties and charted a path to success over the course of his nearly thirty-five-year career.

It is challenging to study Johnson since we have limited biographical information about him. From existing evidence, we know that Johnson was born around 1763 in Baltimore County. He was the son of a White man, George Johnson, and an unknown Black mother, who was an enslaved woman owned by William Wheeler Sr. After being freed in 1782, Joshua moved to Baltimore, where he completed an apprenticeship under blacksmith William Forepaugh and began to take up portrait painting. While it has been suggested that Johnson must have studied art formally under one of his contemporaries such as the famed Charles Willson Peale (1741–1827) or Charles Peale Polk (1767–1822), no direct evidence exists to support this claim. Nevertheless, Johnson very likely possessed a familiarity with works by these artists.[5]

As noted in Catholic church records, Johnson married a woman named Sarah in 1785. Together they had five children, all of whom were baptized in St. Peter’s Church.[6] From the late 1790s through the 1810s, Johnson established himself as one of the leading Federal-era portraitists among upper middle-class Baltimoreans (some of them slave-holding landowners) and competed successfully in a tight market with numerous rival artists who lived nearby. Johnson resided at various addresses in the city center from about 1794 to 1827, and his clients included merchants, tavern owners, sea captains, and religious leaders, many of whom were his neighbors and formed a network of patrons. We must remember that Johnson did not paint “high-society” portraits in the grand manner for elite government officials, as did the Peale family of artists. Rather, his sitters desired straightforward, restrained likenesses of themselves, devoid of drama and pretension. After the mid-1820s, it is believed that Johnson likely died since no there is no record of him in the Baltimore City directories.

As noted in Catholic church records, Johnson married a woman named Sarah in 1785. Together they had five children, all of whom were baptized in St. Peter’s Church.[6] From the late 1790s through the 1810s, Johnson established himself as one of the leading Federal-era portraitists among upper middle-class Baltimoreans (some of them slave-holding landowners) and competed successfully in a tight market with numerous rival artists who lived nearby. Johnson resided at various addresses in the city center from about 1794 to 1827, and his clients included merchants, tavern owners, sea captains, and religious leaders, many of whom were his neighbors and formed a network of patrons. We must remember that Johnson did not paint “high-society” portraits in the grand manner for elite government officials, as did the Peale family of artists. Rather, his sitters desired straightforward, restrained likenesses of themselves, devoid of drama and pretension. After the mid-1820s, it is believed that Johnson likely died since no there is no record of him in the Baltimore City directories.

We note Johnson’s hallmark style (combining elements drawn from European Neoclassical, American Colonial, and Federal portraiture) in paintings like Gentleman of the Shure Family (ca. 1810) as well as in larger, more ambitious works such as The James McCormick Family (ca. 1804–1805). Here, Johnson emphasized his sitters’ close bond with one another and conveyed a sense of upper middle-class prosperity, affluence, material success, and optimism. Indeed, the McCormick family wished to be defined by these qualities and Johnson knew how to capture them, especially through their composed facial expressions, elegant clothing, and fashionable sofa.[7]

We note Johnson’s hallmark style (combining elements drawn from European Neoclassical, American Colonial, and Federal portraiture) in paintings like Gentleman of the Shure Family (ca. 1810) as well as in larger, more ambitious works such as The James McCormick Family (ca. 1804–1805). Here, Johnson emphasized his sitters’ close bond with one another and conveyed a sense of upper middle-class prosperity, affluence, material success, and optimism. Indeed, the McCormick family wished to be defined by these qualities and Johnson knew how to capture them, especially through their composed facial expressions, elegant clothing, and fashionable sofa.[7]

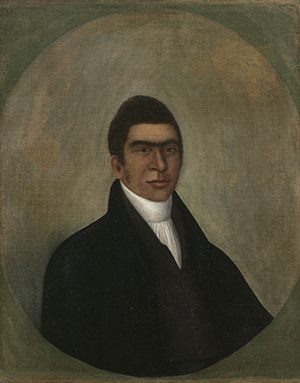

Apart from painting White clients, Johnson also received commissions from Black patrons who were part of Baltimore’s free Black population, one of the nation’s largest during the Federal period. Portrait of Man (Abner Coker) (ca. 1805–1810) is one of two portraits by Johnson that depicts an African American. This work is generally believed to represent Abner Coker (d. 1833), a free Black minister of Baltimore’s African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church. The other related portrait is thought to represent Daniel Coker (1780–1846), a prominent minister, abolitionist, and outspoken critic of slavery.[8] Johnson was likely well acquainted with his subjects and closely connected to the African American community in Baltimore as well as its churches and emergent cultural institutions.[9]

Apart from painting White clients, Johnson also received commissions from Black patrons who were part of Baltimore’s free Black population, one of the nation’s largest during the Federal period. Portrait of Man (Abner Coker) (ca. 1805–1810) is one of two portraits by Johnson that depicts an African American. This work is generally believed to represent Abner Coker (d. 1833), a free Black minister of Baltimore’s African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church. The other related portrait is thought to represent Daniel Coker (1780–1846), a prominent minister, abolitionist, and outspoken critic of slavery.[8] Johnson was likely well acquainted with his subjects and closely connected to the African American community in Baltimore as well as its churches and emergent cultural institutions.[9]

While it is unclear how well Johnson knew Baltimore abolitionists such as Elisha (1750–1824) and Nathan Tyson, Benjamin Banneker (1731–1806), and Daniel Coker, their ideas might have fueled his creative and professional enthusiasm. Specifically, his confidence and resolve might have been driven in part by philosophical sentiments advocating racial equality as well as the dignity, intellectual potential, and advancement of Blacks in post-Revolutionary society.[10] In an era of adversity and inequality, Johnson’s accomplishments provided a significant foundation upon which other nineteenth-century African American artists would build in subsequent decades, most notably Patrick Henry Reason (1816–1898), William Simpson (1818–1872), and Robert S. Duncanson (1821–1872).

Johnson’s life and his work continue to attract considerable attention, most recently with examples of his paintings appearing on the art market, as acquisitions by museums, and as the subject of an important exhibition in 2021.[11] Although many questions remain to be answered about Johnson and his work, we have begun to better understand him and his world.

Selected Bibliography

Bearden, Romare, and Harry Henderson. A History of African-American Artists: From 1792 to the Present. New York: Pantheon Books, 1993.

Bryan, Jennifer, and Robert Torchia. “The Mysterious Portraitist Joshua Johnson.” Archives of American Art Journal 36: 2 (1996), pp. 2–7.

Chieffo-Reidway, Toby Maria. “Joshua Johnson Revisited: Filling the Lacunae.” M.A. Thesis: The College of William and Mary, 1995.

Driskell, David C., and Leonard Simon. Two Centuries of Black American Art. Exhibition catalogue. Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1976.

Farrington, Lisa E. African-American Art: A Visual and Cultural History. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017.

Fulco, Daniel, ed. Joshua Johnson: Portraitist of Early American Baltimore. Exhibition catalogue. Hagerstown, MD: Washington County Museum of Fine Arts, 2021.

Graham, Leroy. Baltimore: The Nineteenth Century Black Capital. Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 1982.

Hartigan, Lynda Roscoe. Sharing Traditions: Five Black Artists in the Nineteenth Century. Exhibition catalogue. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1985.

Perry, Mary Lynn. “Joshua Johnson: His Historical Context and his Art.” M.A. Thesis: The George Washington University, 1983.

Phillips, Christopher. Freedom’s Port: The African-American Community of Baltimore, 1790–1860. Urbana & Chicago, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1997.

Pleasants, Jacob Hall. “Joshua Johnston: The First American Negro Portrait Painter.” Maryland Historical Magazine 37: 2 (1942), pp. 121–49.

Porter, James A. Modern Negro Art. New York: Dryden Press, 1943.

Rockman, Seth. Scraping By: Wage Labor, Slavery, and Survival in Early Baltimore. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009.

Rowell, Charles Henry. “Joshua Johnson.” Callaloo 39: 5 (2016): 1014–1016 and 1084–1090.

Weekley, Carolyn K., et al. Joshua Johnson: Freeman and Early American Portrait Painter. Exhibition catalogue. Baltimore, MD & Williamsburg, VA: The Maryland Historical Society & Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Center, 1987.

Daniel Fulco received his MA and PhD degrees from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. A scholar of European and American art, he was the curator of the exhibition Joshua Johnson: Portraitist of Early American Baltimore (April 17, 2021–January 23, 2022) at the Washington County Museum of Fine Arts in Hagerstown, Maryland. His exhibition catalogues include Joshua Johnson: Portraitist of Early American Baltimore (2021) and Art, Fashion, Symbol, Statement: Tattooing in America, 1960s to Today (2024), both published by the Washington County Museum of Fine Arts.

[1] It should be noted that part of this economic success was built upon the foundations of slavery and forced labor. For more information about Baltimore’s economic and social growth, see Mary Ellen Hayward, “Introduction: Baltimore, 1795–1825,” in Carolyn K. Weekley, et al., Joshua Johnson: Freeman and Early American Portrait Painter, exhibition catalogue (Baltimore, MD & Williamsburg, VA: The Maryland Historical Society & Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Center, 1987), pp. 21–34. On slavery and labor during the period, consult Seth Rockman, Scraping By: Wage Labor, Slavery, and Survival in Early Baltimore (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009).

[2] Baltimore Intelligencer, December 19, 1798.

[3]Baltimore Intelligencer, December 19, 1798.

[4] On the hostile and perilous conditions experienced by African Americans in Federal-period Baltimore, see David Taft Terry, “Joshua Johnston: A Brief Social Biography of the Portrait Painter and the Meanings of Race in His Baltimore, ca. 1763–ca. 1824,” in Daniel Fulco, ed., Joshua Johnson: Portraitist of Early American Baltimore, exhibition catalogue (Hagerstown, MD: Washington County Museum of Fine Arts, 2021), pp. 10–11; Leroy Graham, “Joshua Johnson’s Baltimore,” in Joshua Johnson: Freeman and Early American Portrait Painter, exhibition catalogue, 1987, pp. 36–37.

[5] Johnson’s identity and early biographical information are derived from his manumission papers (collection of the Maryland Center for History & Culture, Baltimore), discovered in 1994 and first published in Jennifer Bryan and Robert Torchia, “The Mysterious Portraitist Joshua Johnson,” Archives of American Art Journal 36: 2 (1996): pp. 2–7. It is possible that Johnson received training as a painter while apprenticing under furniture decorators, carriage builders, and sign painters, who sometimes worked as limners. Johnson might have also painted furniture to supplement his income, especially since he lived in Baltimore’s neighborhood known for its “fancy and painted chair-makers.” See Lynda Roscoe Hartigan, Sharing Traditions: Five Black Artists in the Nineteenth Century, exhibition catalogue (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1985), p. 41; Donald R. Waters and Carolyn J. Weekley, American Folk Portraits: Paintings and Drawings from the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Center (Boston: New York Graphic Society, 1981), p. 133.

[6] Their children were: John (b. 1786); George (b. 1792); Sarah (b. 1794); Mary (b. 1796); and Samuel (b. 1806). Terry, in Joshua Johnson: Portraitist of Early American Baltimore, exhibition catalogue, 2021, p. 8.

[7] Fulco, “Joshua Johnson: Pioneer of American Portraiture,” in Joshua Johnson: Portraitist of Early American Baltimore, exhibition catalogue, 2021, pp. 19–21.

[8] Not a great deal is known about Abner. In 1816, he and his associates co-founded the congregation (consisting of eighteen members) and he served as a deacon of the church beginning in 1822. While Daniel and Abner share the same last name, it is not clear whether they were in fact relatives of one another. James Sidbury has suggested that Abner could have possibly been a half-brother of Daniel. See Sidbury, Becoming African in America: Race and Nation in the Early Black Atlantic (Oxford: Oxford University Press 2007), p. 240; Romare Bearden and Harry Henderson, A History of African-American Artists: From 1792 to the Present (New York: Pantheon Books, 1993), p. 13. For further discussion of Daniel’s abolitionist and missionary publications, see Christopher Phillips, Freedom’s Port: The African-American Community of Baltimore,1790–1860 (Urbana & Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1997), pp. 132–34.

[9] Terry, p. 10.

[10] Bearden and Henderson, 1993, p. 16; Leroy Graham, Baltimore: The Nineteenth Century Black Capital (Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 1982), pp. 24–25; Christopher Phillips, 1997, pp. 83–84; and Fulco, 2021, pp. 29–30.

[11] Recent acquisitions have been made by the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the Minneapolis Institute of Arts, Heritage Frederick (MD), and the Washington County Historical Society (Hagerstown, MD).