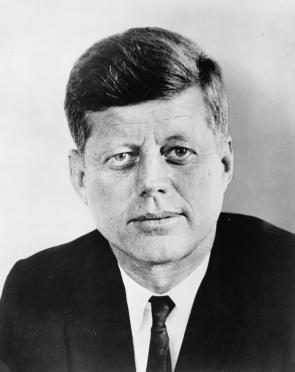

John F. Kennedy’s Inaugural Address

by Michael Nelson

On January 20, 1961, as on most presidential inauguration days, the nation was governed by one president until noon and by another afterward. The contrast between outgoing President Dwight D. Eisenhower and his incoming successor, John F. Kennedy, was dramatic and visible. The youngest man ever to be elected president (Kennedy was forty-three) was replacing the oldest man yet to leave the office (Eisenhower was seventy). A Democrat was replacing a Republican. A celebrated World War II combat hero was replacing the celebrated World War II supreme commander. A professional politician who had served three terms in the House of Representatives and less than two terms as the junior senator from Massachusetts was replacing a career military leader whose first and only elective office was the presidency. Most importantly, perhaps, Kennedy’s election replaced a defender of caution, prudence, and restraint with an advocate of change and energetic leadership.

On January 20, 1961, as on most presidential inauguration days, the nation was governed by one president until noon and by another afterward. The contrast between outgoing President Dwight D. Eisenhower and his incoming successor, John F. Kennedy, was dramatic and visible. The youngest man ever to be elected president (Kennedy was forty-three) was replacing the oldest man yet to leave the office (Eisenhower was seventy). A Democrat was replacing a Republican. A celebrated World War II combat hero was replacing the celebrated World War II supreme commander. A professional politician who had served three terms in the House of Representatives and less than two terms as the junior senator from Massachusetts was replacing a career military leader whose first and only elective office was the presidency. Most importantly, perhaps, Kennedy’s election replaced a defender of caution, prudence, and restraint with an advocate of change and energetic leadership.

The new president’s inaugural address, delivered outdoors from the East Front of the Capitol on a bright but bitterly cold day, accentuated most of these contrasts. Kennedy emphasized his youth by noting that "the torch has been passed to a new generation of Americans—born in this century." Outgoing Vice President Richard Nixon, who like Eisenhower sat on the inaugural platform, reportedly believed that Kennedy offended Ike with that line.

Kennedy reached out to the Soviet Union, the nation’s communist superpower adversary during the Cold War: "Let us never negotiate out of fear. But let us never fear to negotiate." But he also pledged that "we shall pay any price, bear any burden, meet any hardship, support any friend, oppose any foe to assure the survival and the success of liberty." In the best-remembered phrase of his presidency, Kennedy summoned the idealism of the American people: "ask not what your country can do for you—ask what you can do for your country." The call was broadly appealing. It "resonated with liberals who shared Kennedy’s belief in public service, and with conservatives who were weary of government handouts."[1]

Kennedy’s foreign policy was prefigured by his inaugural address. He negotiated an important nuclear test ban treaty with the Soviet Union. But he also resisted communist aggression in a number of global settings, including Berlin, Cuba, and Vietnam. Scholars continue to debate whether Kennedy, who sent 16,500 American soldiers to help defend South Vietnam, would have escalated the war further if he had lived to serve a second term.

Presidents work hard on their inaugural addresses and some, such as Kennedy (and Franklin D. Roosevelt), even strive to create the false impression that they wrote it without any assistance. In his book Kennedy, speechwriter and close advisor Theodore Sorensen described the process by which he and the President-elect crafted the address. "He wanted suggestions from everyone," wrote Sorensen. "He wanted it short. He wanted it to focus on foreign policy. He did not want it to sound partisan, pessimistic or critical of his predecessor. He wanted neither the cold war rhetoric about the Communist menace nor any weasel words that [Soviet leader Nikita] Khrushchev might misinterpret. And he wanted it to set a tone for the era about to begin."[2] All of these goals were met.

During the drafting process, dissatisfied that his and Sorensen’s initial plan to include domestic goals in the address would sound too partisan, Kennedy eventually said: "Let’s drop out the domestic stuff altogether."[3] The omission of domestic issues was upsetting to some aides. "You can’t do this," said Kennedy aide Harris Wofford upon reading the final draft.[4] He argued that Kennedy should say something about the struggle for civil rights in America. Kennedy agreed and added "at home" to a sentence pledging that his administration would support "those human rights to which this nation has always been committed, and to which we are committed today at home and around the world." It was one of the thirty-one changes made in the last hours before delivering the speech.

Hard work on an inaugural address is no guarantor of success. Former Nixon speechwriter William Safire judged only four inaugural addresses to be great: both of Abraham Lincoln’s, Franklin D. Roosevelt’s first, and Kennedy’s. Stephen Hess, a presidential scholar and former Eisenhower speechwriter, adds two more to this list: Thomas Jefferson’s first and Woodrow Wilson’s second. Of the six, Kennedy’s is not only the most recent, delivered in 1961, but also the only one delivered in the absence of a national crisis.

JFK’s inaugural address was a model of the genre in its elevated language, call for divine assistance, stirring evocation of national traditions and values, and above all in its unifying character. In that sense, it followed the path blazed by George Washington in the first inaugural address ever delivered by a president. The Kennedy address’s twelve-minute length was perfect, not too long, not too short.

Kennedy did not survive even his first term. During the fall of 1963, the President made several trips around the country to build support for his 1964 reelection bid. On November 22, while riding through Dallas, Texas, in an open car, Kennedy was shot in the head and neck. Shortly afterward, he died at a nearby hospital without having regained consciousness. The police quickly apprehended his assassin, ex-Marine and communist-sympathizer Lee Harvey Oswald. But Oswald’s own murder while in police custody by Dallas nightclub owner Jack Ruby fostered speculation that the Kennedy assassination may have been the product of a conspiracy. A special presidential commission headed by Chief Justice Earl Warren concluded in 1964 that Oswald had acted alone.

The combination of Kennedy’s youth and glamour and his sudden, violent death has given the late president a special place in the consciousness of the American people. Polls often find that the public regards Kennedy as one of the greatest presidents in history, a verdict debated by historians. In my experience as a teacher, twenty-first-century college students know only two sentences from all of the inaugural addresses delivered by all of the presidents: FDR’s "the only thing we have to fear is fear itself" and JFK’s "ask not."

[1] Ted Sorensen, Counselor: A Life at the Edge of History (New York: Harper, 2008), 224.

[2] Ted Sorensen, Kennedy (New York: Harper Collins, 2010), 240.

[3] Sorensen, Kennedy, 242.

[4] Richard Reeves, President Kennedy: Profile of Power (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1994), 667.

Michael Nelson is the Fulmer professor of political science at Rhodes College and a senior fellow at the University of Virginia’s Miller Center. He is coauthor of The American Presidency: Origins and Development, 1776–2011 (2011).