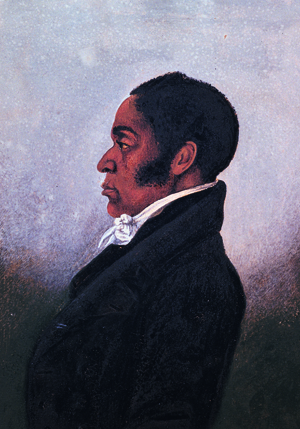

James Forten and American Freedom

by Julie Winch

James Forten never forgot what he witnessed on September 2, 1781. He spent most of the day, which happened to be his fifteenth birthday, standing in the street with thousands of other Philadelphians and watching General Washington’s troops march through the city on their way to face Cornwallis’s army in Virginia. What Forten remarked on decades later in a letter to his friend and fellow abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison was the presence in the ranks of “several Companies of Coloured People, as brave Men as ever fought.”[1] The sight of those Black soldiers heading off to battle alongside their White comrades strengthened the young James Forten in his faith that the cause of American independence knew no lines of race. He had already decided where his loyalties lay. Just a couple of weeks after that memorable birthday, he reported back to the captain of theRoyal Louis (named for America’s ally, Louis XVI of France) . He had sailed on the American privateer’s first cruise. He had risked his life when the ship had come under enemy fire and he was prepared to do so again. Within days, his commitment to the American cause, his cause, would be put to the test when a British warship captured the Royal Louis. James Forten received and rejected a remarkably generous offer to switch sides. “I have been taken prisoner for the liberties of my country,” he told the British captain who made him that offer, “and never will prove a traitor to her interest.”[2] His decision earned him seven months of captivity in a disease-ridden prison hulk and almost cost him his life.

James Forten never forgot what he witnessed on September 2, 1781. He spent most of the day, which happened to be his fifteenth birthday, standing in the street with thousands of other Philadelphians and watching General Washington’s troops march through the city on their way to face Cornwallis’s army in Virginia. What Forten remarked on decades later in a letter to his friend and fellow abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison was the presence in the ranks of “several Companies of Coloured People, as brave Men as ever fought.”[1] The sight of those Black soldiers heading off to battle alongside their White comrades strengthened the young James Forten in his faith that the cause of American independence knew no lines of race. He had already decided where his loyalties lay. Just a couple of weeks after that memorable birthday, he reported back to the captain of theRoyal Louis (named for America’s ally, Louis XVI of France) . He had sailed on the American privateer’s first cruise. He had risked his life when the ship had come under enemy fire and he was prepared to do so again. Within days, his commitment to the American cause, his cause, would be put to the test when a British warship captured the Royal Louis. James Forten received and rejected a remarkably generous offer to switch sides. “I have been taken prisoner for the liberties of my country,” he told the British captain who made him that offer, “and never will prove a traitor to her interest.”[2] His decision earned him seven months of captivity in a disease-ridden prison hulk and almost cost him his life.

James Forten’s decision to fight—and suffer—for the cause of independence was not one shared by the majority of Black people. Several thousand did serve in the American forces, but tens of thousands more sided with the British, who promised them freedom, even if that promise was made to undermine the American war effort rather than from a sense that slavery violated basic human rights. Forten’s choice of loyalties was rooted in who and what he was. He was freeborn, as was his father before him. His paternal great-grandfather had been brought to Pennsylvania as a slave around the time of William Penn’s own arrival. That man’s son had somehow managed to gain his freedom. Although James and his father, Thomas, would never know what it was to be enslaved, James’s mother, Margaret, almost certainly did. She and Thomas apparently waited years to start a family until they had bargained for her freedom. The law in Pennsylvania, as in most of Britain’s American colonies, stated that children would inherit their mother’s free or unfree status. Thomas and Margaret would not bring a child into the world until they could be sure that that child would be born free. Margaret Forten was forty-one in 1763 when James’s sister was born and forty-four in 1766 when he was born.

The Fortens were luckier than most of their neighbors in that they were legally free in a city where the vast majority of Black people were enslaved. Thomas also had a skilled trade, whereas many Philadelphians, regardless of race, were unskilled day laborers. Thomas Forten worked as a sailmaker in the sail-loft of a White man, Robert Bridges. James no doubt hoped to follow in his father’s footsteps one day, and as a child he evidently began learning the basics of the sailmaker’s craft. But in 1773 or 1774 Thomas died, plunging his family into near destitution. While James needed to take whatever work was available to help put food on the table, his mother insisted that he continue with his education, at least on a part-time basis. For two years he attended the Quakers’ African School, learning to read and write and do basic mathematics. His hard-won literacy developed into a love of reading and a way with words that would benefit not only James Forten himself but his entire community in the years to come.

Not yet in his teens when his family’s struggles to stave off poverty obliged him to go out to work full time, James Forten was very much aware of the larger political and military struggles going on around him. He recalled being in the midst of an excited crowd in the State House Yard in July of 1776 and hearing the Declaration of Independence read in public for the first time. When British forces took possession of Philadelphia in 1777, many residents fled, but James and his mother and sister stayed. Philadelphia was their home and they had nowhere else to go. They were still there when the army of occupation left and Philadelphia became once more the capital of the new nation. It also became a privateering base, and at age fourteen, motivated by patriotism and the chance of prize money, James Forten signed up on board the Royal Louis, knowing full well that captains desperate for recruits could not afford to turn away volunteers on the basis of skin color. He was between cruises and enjoying a few weeks at home with his family when he watched Washington’s troops march through Philadelphia on their way to Yorktown.

When the war finally ended, James Forten found work with the man who had employed his father. Sailmaker Robert Bridges was no advocate of racial justice. He owned a couple of slaves and felt no need to apologize for doing so. However, he recognized talent and the drive to succeed when he saw them, and he saw them in James Forten. He took Forten on as an apprentice and eventually promoted him to foreman. When some of his White workers grumbled about taking orders from a Black man, Bridges told them they were welcome to seek work elsewhere. In 1798, when Bridges retired, he arranged for Forten to take over the sail-loft. With introductions to the city’s leading shipowners, and assurances that his one-time apprentice had truly mastered his trade, Bridges set Forten on the path to prosperity.

Plowing his profits into expanding his sail-loft and making judicious investments in real estate, as well as loaning money at interest, James Forten grew wealthy. His loft had no shortage of orders. Shipowners came to him because of the quality of work his racially integrated workforce produced. (Forten’s policy was to hire and promote based solely on ability.) He could have focused on making money and ignored the world around him, but he did not. By the time he took over the sail-loft he had already found his voice as a champion of racial equality. He spoke out on behalf of the growing free community of color in Philadelphia and beyond. He also attacked the institution of slavery—and he did so by referring again and again to what he insisted were the nation’s founding principles. They were, after all, the same principles that had led him off to war, and the same principles he believed he had seen displayed in that military parade that had just happened to coincide with his fifteenth birthday.

James Forten was seventy-five—old by the standards of his day—when he died in the spring of 1842. He was a husband, a father, and a grandfather. Although it troubled him deeply in his later years to see that many White Americans had apparently forgotten what, at least in his mind, the Revolution had been fought for, he refused to abandon hope. “[W]e live in stirring times,” he declared, “and every day brings news of some new effort for liberty . . . [O]nward, onward, is indeed the watchword.”[3] If he feared he would not live to see the promise of America fulfilled, he believed to the end of his life that one day his descendants would.

Julie Winch is professor of history at the University of Massachusetts Boston. She is the author of several books, including A Gentleman of Color: The Life of James Forten (Oxford University Press, 2002), which won the American Historical Association’s Wesley Logan Prize, and Between Slavery and Freedom: Free People of Color in America from Settlement to the Civil War (Rowman & Littlefield, 2014).

[1] James Forten to William Lloyd Garrison, February 23, 1831, Antislavery Manuscripts, Boston Public Library.

[2] Robert Purvis, Remarks on the Life and Character of James Forten, Delivered at Bethel Church, March 30, 1842 (Philadelphia: Merrihew & Thompson, 1842), 6.

[3] James Forten to William Lloyd Garrison, October 20, 1831, Antislavery Manuscripts, Boston Public Library.