Imperial Rivalries

by Peter C. Mancall

by Peter C. Mancall

When Christopher Columbus made his plans to sail westward across the Atlantic, he first set off across Europe to find sponsors. His brother Bartholomew went to the court of the English King Henry VII (who turned him down, much to the regret of later Britons who realized the opportunity they had missed). Eventually Columbus received support from King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella of Spain. He sailed westward in search of a new route to the riches of East Asia and the Southwest Pacific, but he also ventured forth as an agent of a particular European state. Columbus therefore claimed (and renamed) new lands for Spain and planted the Spanish flag to mark its expanded territory.

Columbus’s activities before and during his historic journey reflected his understanding of European politics in the late fifteenth century. Venturing westward was too expensive for an individual to fund independently, hence governments sponsored such voyages. European policy makers knew that they were always competing with each other. They also understood that their rivalries must not offend the church; until the Protestant Reformation, religious authority belonged to the pope and his court in Rome, along with his representatives across Europe.

PRINCIPALITIES AND KINGDOMS

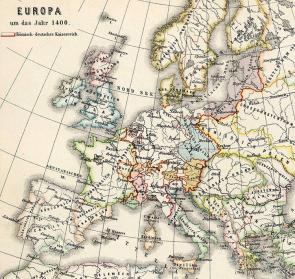

Unlike modern nations, European states in the fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries were not especially well organized or efficient. Any accurate map of Europe revealed that principalities, not modern nation-states, dominated the continent. There was no such entity as "Ireland," for example. The island instead was the home of four provinces—Leinster, Munster, Connacht, and Ulster—ruled by chieftains, each of whom controlled a large territory where inhabitants paid taxes in exchange for protection. The leaders of such petty fiefdoms and rulers of larger kingdoms tended to see their neighbors as rivals; just as Leinster feuded with Munster, England remained at odds with France, and France competed with the Spanish kingdoms. Long-distance military expeditions against more distant foreign powers were relatively rare because they were so expensive. European crusaders ventured out to retake the Holy Land from the late eleventh to the late thirteenth centuries, hoping to lay claim to Jerusalem and protect it from the growing power of Muslim states, but also to make a tidy profit in trade with Middle Eastern merchants. Along the way, these Christian warriors often raided the territories they passed through, engendering animosities that lasted for generations.

Unlike modern nations, European states in the fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries were not especially well organized or efficient. Any accurate map of Europe revealed that principalities, not modern nation-states, dominated the continent. There was no such entity as "Ireland," for example. The island instead was the home of four provinces—Leinster, Munster, Connacht, and Ulster—ruled by chieftains, each of whom controlled a large territory where inhabitants paid taxes in exchange for protection. The leaders of such petty fiefdoms and rulers of larger kingdoms tended to see their neighbors as rivals; just as Leinster feuded with Munster, England remained at odds with France, and France competed with the Spanish kingdoms. Long-distance military expeditions against more distant foreign powers were relatively rare because they were so expensive. European crusaders ventured out to retake the Holy Land from the late eleventh to the late thirteenth centuries, hoping to lay claim to Jerusalem and protect it from the growing power of Muslim states, but also to make a tidy profit in trade with Middle Eastern merchants. Along the way, these Christian warriors often raided the territories they passed through, engendering animosities that lasted for generations.

SPAIN AND PORTUGAL AND THE POPE

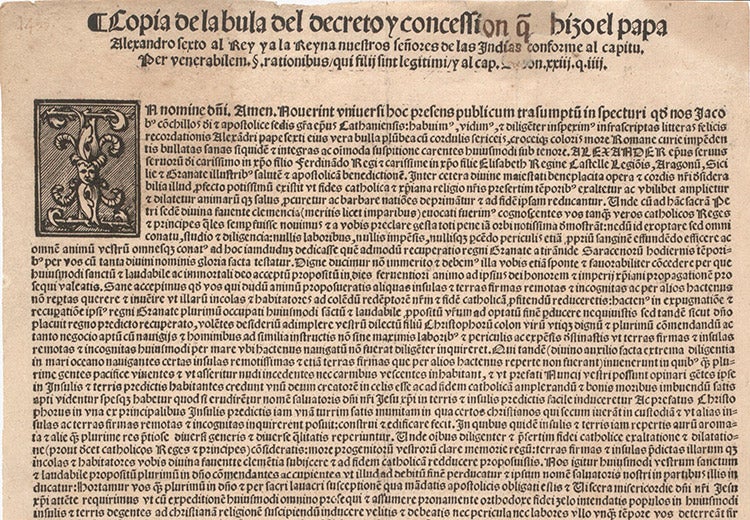

The most important national rivalries for the Western Hemisphere took shape after 1492. The same year that Columbus sailed westward, the combined forces of the Spanish kingdoms under the Castilian Queen Isabella and the Aragonese King Ferdinand reclaimed Iberia from the Islamic Moors; they also expelled Jews who lived there, or forced those who remained to convert to Christianity (at which point they became known as Marranos or conversos). Both actions endeared the monarchs to Christian leaders. On May 4, 1493, Pope Alexander VI (a Spaniard), after hearing about Columbus’s discovery of a "new world," rewarded Ferdinand and Isabella with the Bull of Donation, also known as the Inter caetera, which authorized Spain to colonize and exploit American lands despite earlier papal documents that had granted Portugal control of newly discovered regions.  The following year the Spanish and Portuguese rulers, whose ships were then engaged in the most far-reaching European exploratory ventures, agreed to the terms of the Treaty of Tordesillas, which established a geographical line approximately 1,200 nautical miles west of the Cape Verde islands. This boundary entitled the Portuguese to lay claim to Brazil, which they colonized in the sixteenth century, in addition to lands newly seen by Europeans in the Old World. Spain, meanwhile, could claim everything that lay to the west of the line.

The following year the Spanish and Portuguese rulers, whose ships were then engaged in the most far-reaching European exploratory ventures, agreed to the terms of the Treaty of Tordesillas, which established a geographical line approximately 1,200 nautical miles west of the Cape Verde islands. This boundary entitled the Portuguese to lay claim to Brazil, which they colonized in the sixteenth century, in addition to lands newly seen by Europeans in the Old World. Spain, meanwhile, could claim everything that lay to the west of the line.

These papally sanctioned agreements propelled the Spanish and Portuguese to establish colonies in the Western Hemisphere as well as (for the Portuguese) areas in and near the Indian Ocean and the southwestern Pacific. In addition to the voyages of Columbus, the Spanish sent other would-be conquerors to lay claim to new territories, including Hernán Cortés, who led Spanish forces to victory over the Aztecs in Mexico in the late 1510s, and Francisco Pizarro, whose army emerged victorious over the Incas in Peru in the 1530s. In the years that followed, Spanish conquerors raised their standard across much of southwest North America as well as Florida. Spanish and Portuguese colonizers eagerly extracted wealth from these new territories, especially in the form of hordes of gold, silver, and precious jewels. They made sure to send gifts of thanks to their religious patrons. The pope purportedly used some of the gold sent by the Spanish to cover the ceiling of Rome’s ancient basilica and one of its greatest churches, Santa Maria Maggiore. The extraction of this wealth came at a high cost not only to America’s indigenous peoples, who witnessed the desecration of temples to satisfy the lust of the conquistadores, but also to humanity’s history and art, since the newcomers typically melted Native icons and thereby erased ancient cultures.

ENGLAND, FRANCE, AND HOLLAND JOIN THE RACE

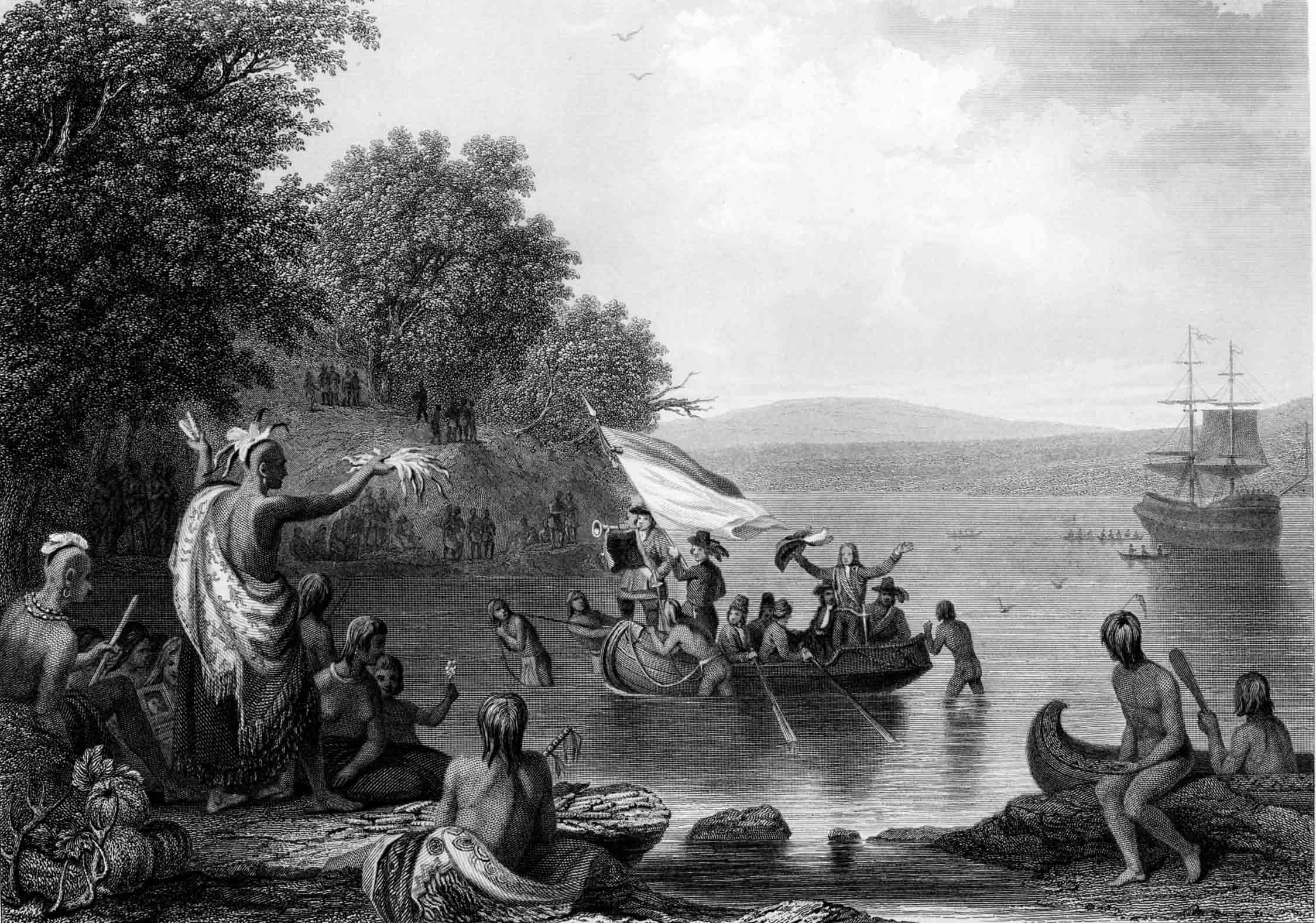

The agreements of the early 1490s made sense in a Europe where the Spanish and the Portuguese were the dominant maritime players. But over the course of the sixteenth century other Europeans also recognized the benefits of long-distance commerce and conquest. The French had been interested in possibilities of Atlantic enterprise since the early decades of the sixteenth century.  The Breton explorer Jacques Cartier made three voyages—in 1534, 1535–1536, and 1541–1542—as part of an effort to expand knowledge of North America and identify a possible route through the continent to the South Sea. He never found that passage, but he did explore the St. Lawrence Valley and laid an initial French claim to Canada. By mid-century, a group of mapmakers clustered in Dieppe had produced a series of new maps, based on Portuguese sea charts (called portolans), which hinted at what explorers would find. In July 1608 Samuel Champlain, after exploring other territory farther south, established Quebec City, which would become the central colonial outpost of New France. Such grand assertions—such as claiming ownership of Canada based on establishing a relatively small community—were not unique. In 1609, the Dutch-employed English captain Henry Hudson, after failing to find the Northeast Passage (which he hoped would take him through open water north of Russia to the Pacific), crossed the Atlantic and eventually made his way up the river that now bears his name. In the years that followed the Dutch laid a formal claim to this region, calling it New Netherland and establishing their main outpost on the island of Manhattan.

The Breton explorer Jacques Cartier made three voyages—in 1534, 1535–1536, and 1541–1542—as part of an effort to expand knowledge of North America and identify a possible route through the continent to the South Sea. He never found that passage, but he did explore the St. Lawrence Valley and laid an initial French claim to Canada. By mid-century, a group of mapmakers clustered in Dieppe had produced a series of new maps, based on Portuguese sea charts (called portolans), which hinted at what explorers would find. In July 1608 Samuel Champlain, after exploring other territory farther south, established Quebec City, which would become the central colonial outpost of New France. Such grand assertions—such as claiming ownership of Canada based on establishing a relatively small community—were not unique. In 1609, the Dutch-employed English captain Henry Hudson, after failing to find the Northeast Passage (which he hoped would take him through open water north of Russia to the Pacific), crossed the Atlantic and eventually made his way up the river that now bears his name. In the years that followed the Dutch laid a formal claim to this region, calling it New Netherland and establishing their main outpost on the island of Manhattan.

THE SEARCH FOR THE NORTHWEST PASSAGE

![This map shows an early representation of the purported Northwest Passage above North America. Novi Orbis Pars Borealis, [1600], by Matthias Quad (Historic Maps Collection, Princeton University)](https://www.gilderlehrman.org/sites/default/files/imagecache/inline-2col-float/essay-images/northwestpassage.jpg) The English, for their part, schemed to gain control of much of North America, hoping—as did the French and the Dutch—to find the Northwest Passage, a water route to Asia that European mapmakers were convinced existed somewhere in North America. Whoever found that route would be able to control passage from the Atlantic to the South Sea (now the Pacific Ocean) and from there to Japan, China, and the Spice Islands.

The English, for their part, schemed to gain control of much of North America, hoping—as did the French and the Dutch—to find the Northwest Passage, a water route to Asia that European mapmakers were convinced existed somewhere in North America. Whoever found that route would be able to control passage from the Atlantic to the South Sea (now the Pacific Ocean) and from there to Japan, China, and the Spice Islands.

Since Europeans had fallen in love with East Asian silk as well as the cinnamon, cloves, nutmeg, and peppers from places like Banda much earlier, these sixteenth-century explorers knew there was enormous demand for whatever they could bring back. A northern route would in theory drastically cut the length of the journey, thus ensuring that the spices sailors hauled home would be fresher than those brought by other Europeans who took southern routes around Africa or South America. A quick water route would also have enabled northern Europeans to cut off both the Spanish, who got to the East efficiently only after they claimed Mexico and built a major port at Acapulco (so they could send silver to the Philippines to purchase spices and silks), as well as the Portuguese, who reached the Pacific by sailing around Africa and then across the Indian Ocean. Even more important, the discovery of the northerly route would (at least in the opinion of the English) prove that God favored the Reformation and hence reward those who broke away from Rome—a far greater prize than the demarcation line with which the pope had rewarded Spain and Portugal.

RELIGIOUS STRIFE AND THE MAP OF THE "NEW WORLD"

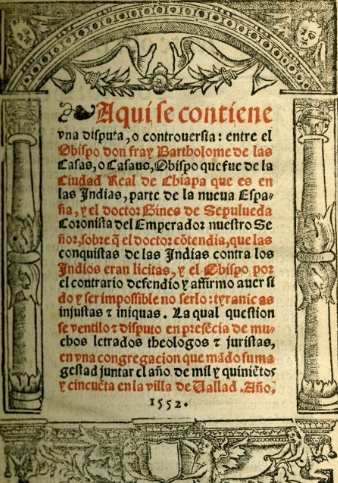

It is impossible to overstate the significance of religious strife in post-Reformation Europe. After the Reformation, northern European Protestants were eager to establish claims in new territories so that they could prevent the spread of the faith now known as Roman Catholicism. Under Queen Elizabeth I, a daughter of Henry VIII, the English renewed their longstanding effort to colonize Ireland, which had begun in the twelfth century but had never fully succeeded. Elizabeth’s commanders, fueled by the idea that Irish Christianity was inferior to their own and thus needed to be eradicated, employed brutal tactics on the battlefield. This experience shaped the mindset of some of the English who later joined missions across the Atlantic. The English, who would eventually gain control of the Atlantic coast of North America between Canada and Florida, made their contest with Rome a central part of their arguments for conquest and colonization. They were aided, as it turned out, by a report written by a one-time slaveholder turned Dominican missionary named Bartolomé de Las Casas, who in 1552 published (in Seville) a book called A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies. The book contained lurid details about torture and murder perpetrated by Spanish conquistadors in the Indies, which Las Casas urged the Spanish court to recognize in order to halt such violent tactics. When the book appeared in an English language translation in London in 1583, its purpose had less to do with changing Spanish tactics. It became a testimony to the inherently barbarous nature of Iberian Catholics, a theme picked up by other English authors in the 1580s and 1590s. These texts helped prompt reluctant Protestants to commit precious resources to the creation of overseas colonies, thereby expanding the European imperial contest for dominance in the Atlantic basin.

It is impossible to overstate the significance of religious strife in post-Reformation Europe. After the Reformation, northern European Protestants were eager to establish claims in new territories so that they could prevent the spread of the faith now known as Roman Catholicism. Under Queen Elizabeth I, a daughter of Henry VIII, the English renewed their longstanding effort to colonize Ireland, which had begun in the twelfth century but had never fully succeeded. Elizabeth’s commanders, fueled by the idea that Irish Christianity was inferior to their own and thus needed to be eradicated, employed brutal tactics on the battlefield. This experience shaped the mindset of some of the English who later joined missions across the Atlantic. The English, who would eventually gain control of the Atlantic coast of North America between Canada and Florida, made their contest with Rome a central part of their arguments for conquest and colonization. They were aided, as it turned out, by a report written by a one-time slaveholder turned Dominican missionary named Bartolomé de Las Casas, who in 1552 published (in Seville) a book called A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies. The book contained lurid details about torture and murder perpetrated by Spanish conquistadors in the Indies, which Las Casas urged the Spanish court to recognize in order to halt such violent tactics. When the book appeared in an English language translation in London in 1583, its purpose had less to do with changing Spanish tactics. It became a testimony to the inherently barbarous nature of Iberian Catholics, a theme picked up by other English authors in the 1580s and 1590s. These texts helped prompt reluctant Protestants to commit precious resources to the creation of overseas colonies, thereby expanding the European imperial contest for dominance in the Atlantic basin.

EXPLORATION BOOK SHOP

Although Europeans looking westward across the Atlantic were in constant competition for lands, riches, and souls, they shared information about new discoveries with surprising frequency. When Columbus returned from his first journey, his initial testimony quickly appeared in a book now known to scholars as the Barcelona Letter of 1493, after the place where a publisher first printed it. Soon editions in other languages appeared, including one published in Basel, Switzerland, also in 1493, which included crude woodcuts created by an artist who had read the text and tried to create a visual rendering of Columbus’s initial encounter with the Arawaks or Tainos. By 1500, descriptions of Columbus’s voyages had spread across Europe.

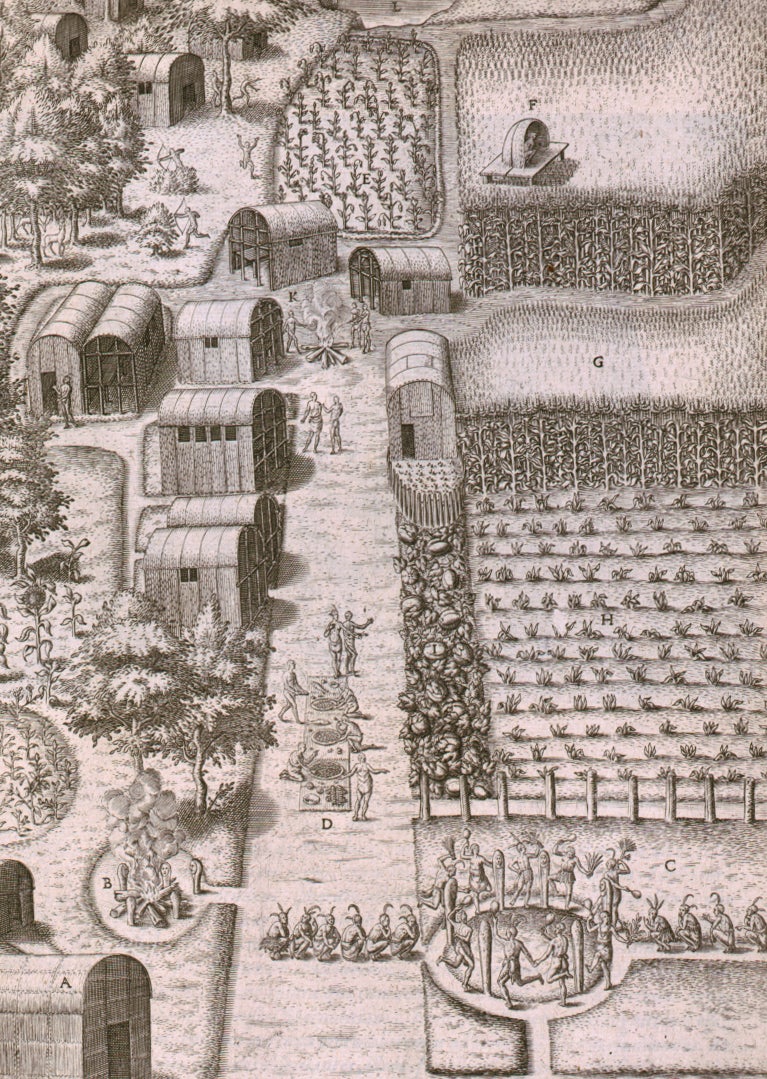

The spread of works about Columbus was only the beginning. Over the course of the sixteenth century, when printing presses proliferated across Europe, scores of new books testified to both the opportunities and dangers of the Western Hemisphere. One of those books was written by a young English mathematician named Thomas Harriot, who had traveled to the outer banks of modern North Carolina, in 1585. In 1588 Harriot produced a small book rich with details about the region he had seen, the peoples who lived there, and the natural resources that could be extracted from its landscape. Harriot called his book A Brief and True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia. Two years later, an avid promoter of English colonization named Richard Hakluyt the younger (to differentiate him from his cousin) took the text from Harriot’s book and worked with a Flemish engraver based in Frankfurt-am-Main, Theodor de Bry, to produce the first fully illustrated published account of any Native American population. In 1590 English, French, German, and Latin versions all rolled off de Bry’s presses.

What could explain such a publishing strategy? After all, France was still a Catholic nation, as were parts of German-speaking central Europe, so a book extolling the virtues of territory claimed by the English might only feed the desire of English foes to seize the region. Yet Hakluyt and the others embraced the multi-language edition because they recognized that the European scientific community needed to know about new discoveries. The scholars among them could read Latin, but by the late sixteenth century vernacular languages had also come to be important in the transmission of knowledge, as people who were not scholars became interested in the world around them and the new discoveries.

The four-language edition of Harriot’s Brief and True Report serves as a cautionary tale for scholars trying to understand European imperial rivalries during the initial colonization of the Americas. Europeans competed fiercely for territories and souls that they believed they could and should conquer. They also mounted legal arguments about which European nation could justly claim which parts of the non-European world. These arguments included a tract written by a Dutch jurist named Hugo Grotius, published in 1609 as Mare Liberum (the Free Sea), which aimed at undermining the Treaty of Tordesillas. Grotius asserted that the Spanish and Portuguese could not lay permanent claim to territories based on a geographical line drawn through the ocean, because no one could own the sea.

By the time the English founded Jamestown, Virginia, in 1607, imperial rivals jostled for control of the resources of the Atlantic basin. Eventually European contests would spawn American battles too, with far-ranging consequences for the Native peoples who came into contact with newcomers eager to establish a firm grip over the Western Hemisphere.

Peter C. Mancall is the Andrew W. Mellon Professor of the Humanities and Professor of history and anthropology at the University of Southern California and the director of the USC-Huntington Early Modern Studies Institute. His publications include Fatal Journey: The Final Expedition of Henry Hudson—A Tale of Mutiny and Murder in the Arctic (2009), Hakluyt’s Promise: An Elizabethan’s Obsession for an English America (2007), and Travel Narratives from the Age of Discovery: An Anthology (2006). He is currently working on American Origins, which will be volume one of the Oxford History of the United States.