Historical Archaeology, Kingsley Plantation, and the Construction of Past Time

by James M. Davidson

Archaeology is the study of the past—people and everything they were, their public acts and private hopes—or at least it is an earnest attempt to “construct” this past through a meticulous examination of material objects, the greater landscape, and the social milieu under which these men, women, and children lived and died. In myriad ways, history preserves with greatest clarity the dominant narrative of society, but its alternative voices and experiences are inevitably less well-known, often willfully suppressed, and occasionally all but lost. The power of archaeology is that it can literally rescue lost time and resurrect silenced voices. This is certainly true within the field of historical archaeology, which is the study of European expansion, colonialism, and capitalism as well as the impacts of these and other forces on both European and non-Western peoples across the globe from the fifteenth century to the present day.[1]

Although archaeological research of the historical era emerged in the United States as a unique subfield in the 1930s, it wasn’t until 1967 that a critical mass of like-minded scholars gathered to found the Society for Historical Archaeology. In an era when the Civil Rights Movement in the United States was finally achieving its hard-won legislative successes for African Americans, a small research project in historical archaeology revisited one of the archetypal sites through which the black experience in this country had been forged—a southern plantation.

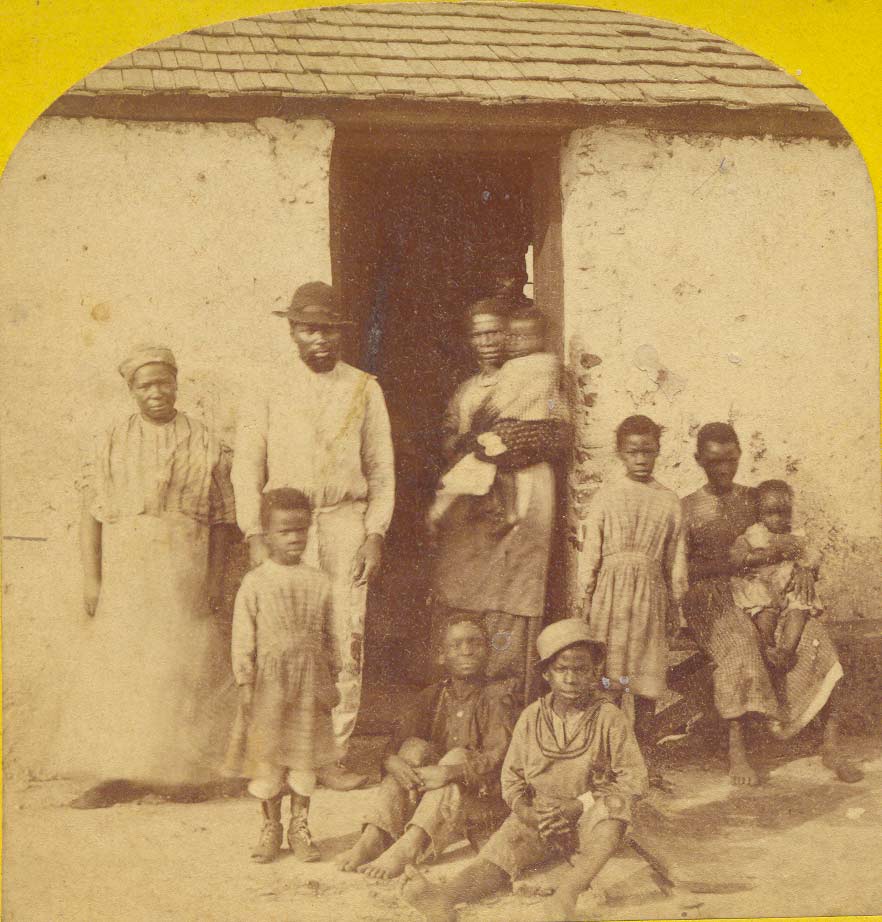

In April 1968, Americans mourned the loss of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., assassinated at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis. Three months later, University of Florida undergraduate students, led by Charles Fairbanks, undertook the first deliberate scientific archaeological excavation of a slave cabin ever conducted in the western hemisphere.[2] This marked the beginnings of a plantation archaeology that sought to understand slavery from the perspective of enslaved Africans. The focus of their research was a tabby-walled slave cabin at Kingsley Plantation on Fort George Island, Florida, located within the greater Jacksonville metropolitan area and part of the Timucuan Ecological and Historical Preserve National Park.

In April 1968, Americans mourned the loss of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., assassinated at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis. Three months later, University of Florida undergraduate students, led by Charles Fairbanks, undertook the first deliberate scientific archaeological excavation of a slave cabin ever conducted in the western hemisphere.[2] This marked the beginnings of a plantation archaeology that sought to understand slavery from the perspective of enslaved Africans. The focus of their research was a tabby-walled slave cabin at Kingsley Plantation on Fort George Island, Florida, located within the greater Jacksonville metropolitan area and part of the Timucuan Ecological and Historical Preserve National Park.

Without any archaeological precedent, Fairbanks’s research was inspired by the Civil Rights Movement itself as well as by the work of cultural anthropologists who had been documenting the African Diaspora since the 1920s. The principal architect of this research was Melville Herskovits, who throughout his career but especially with his 1941 book, The Myth of the Negro Past, helped shatter the fiction that African-descended people in the Americas had failed to retain any remnants of African cultures or beliefs. These cultural retentions were termed “Africanisms,” and it was the search for material evidence of these “Africanisms” that inspired Fairbanks’s excavations.

What began as “plantation archaeology” has expanded well beyond this original vision to include the black experience in diverse locales and social conditions spanning the 1500s to the Cold War era, and is now termed the archaeology of the African Diaspora. Many aspects of the hidden lives of enslaved peoples have been made visible through this work. For example, Fairbanks and other researchers after him discovered that excavated slave cabins often contained evidence of firearms, in the form of lead shot and bullets, lead sprue from casting bullets in molds, gunflints or percussion caps, and gun parts. Slaves with guns are not commonly noted in accounts of the era, but in several documented examples, they are undeniable as historical fact.

A major thrust of research since the 1970s has been the search for African identity, and abundant evidence for lifeways that were deeply rooted in African cultures, especially aspects of West African religions and spirituality, has been repeatedly recovered archaeologically.

Fairbanks began his search for evidence of African material culture at Kingsley Plantation because the majority of the enslaved people there were African-born, and because of the unusual relationship that Zephaniah Kingsley, the plantation’s founder, had with them. Kingsley was born in Scotland in 1766, and by the 1790s was a slave trader traveling throughout Africa, the Caribbean, and Brazil. He arrived in Florida in 1803 and while visiting Cuba in 1806 purchased an African girl named Anta (later Anna) Madgigine Jai. He took Anna as his “wife” when she was just thirteen years old, and as Kingsley rejected Christianity, their marriage “was celebrated and solemnized by her African custom.” Zephaniah and Anna lived as husband and wife for the rest of their lives, raising four children.[3]

The Kingsleys moved to Fort George Island with more than 100 Africans in 1814, building thirty-two tabby slave cabins, among other infrastructure, and creating the plantation that Fairbanks would excavate 154 years later. It flourished for some twenty-five years, before the family immigrated to Haiti in 1839, leaving the property with Kingsley’s nephew. This move was triggered by Florida’s passage of legislation, biased against women and those of African descent, regarding inheritance.[4]

The Kingsleys moved to Fort George Island with more than 100 Africans in 1814, building thirty-two tabby slave cabins, among other infrastructure, and creating the plantation that Fairbanks would excavate 154 years later. It flourished for some twenty-five years, before the family immigrated to Haiti in 1839, leaving the property with Kingsley’s nephew. This move was triggered by Florida’s passage of legislation, biased against women and those of African descent, regarding inheritance.[4]

Kingsley did not practice Christianity and opposed attempts to Christianize his Africans,[5] whom he held in unusually high esteem, stating to abolitionist writer Lydia Maria Child that “I always thought and said, that the colored race were superior to us, physically and morally.”[6] In short, although Kingsley was a white enslaver with many of the racial biases of the era, he still allowed the Africans on his plantation the autonomy to maintain their own unique traditions or to initiate new rituals and beliefs derived from exposure to other African cultures on the island.

![A modern view of a portion of the east arc of tabby slave cabins. [Cabins E-1 through E-4]. (Courtesy of James M. Davidson) A modern view of a portion of the east arc of tabby slave cabins. [Cabins E-1 through E-4]. (Courtesy of James M. Davidson)](/sites/default/files/Figure3.jpg) For eight summers between 2006 and 2013, I led a series of archaeological field schools at Kingsley Plantation, forging a partnership between the National Park Service and the University of Florida. Our goal was to revisit this founding site for African Diaspora archaeology, but now armed with a greater understanding of how African cultures in the New World might be rendered visible through archaeology. In a combined forty-eight weeks of field research and with the cumulative efforts of more than 120 students and volunteers, our primary focus was within the slave quarters, with excavations exposing all or portions of the interiors of four cabins—W-12, W-13, W-15, and E-10—their adjoining yards, and a water well. We also rediscovered the lost Kingsley-era African Burial Ground, and in this hallowed space identified the graves of five men, women, and children, who had experienced enslavement and lived and died two hundred years ago.

For eight summers between 2006 and 2013, I led a series of archaeological field schools at Kingsley Plantation, forging a partnership between the National Park Service and the University of Florida. Our goal was to revisit this founding site for African Diaspora archaeology, but now armed with a greater understanding of how African cultures in the New World might be rendered visible through archaeology. In a combined forty-eight weeks of field research and with the cumulative efforts of more than 120 students and volunteers, our primary focus was within the slave quarters, with excavations exposing all or portions of the interiors of four cabins—W-12, W-13, W-15, and E-10—their adjoining yards, and a water well. We also rediscovered the lost Kingsley-era African Burial Ground, and in this hallowed space identified the graves of five men, women, and children, who had experienced enslavement and lived and died two hundred years ago.

To see aspects of religiosity through material objects, it is necessary to understand the belief systems of the African parent cultures from which these people were descended, which typically include a belief in the reincarnation of the soul, a pantheon of deities with specific needs and powers, and lesser spirits both benign and malevolent. In particular we focused on cultures known to have been represented among Kingsley’s slaves—the Calabar, Ibo, and related peoples from what is now modern Nigeria; the Susu people and other cultures from Upper Guinea; and Central and East African cultures derived from the slave port at Zanzibar.[7]

Since many aspects of religion are ephemeral actions, we focused our efforts on recognizing religious paraphernalia, or at least the core symbols that might be mapped onto everyday objects accessible on the island. To be able to “see” common artifacts as ones potentially imbued with religiosity, researchers rely on the context of the artifacts, any modifications to the object or objects, and extensive ethnographic research. Using this process, several artifacts recovered during the 2006 through 2013 field seasons are believed to be associated with African spiritualties.

Since many aspects of religion are ephemeral actions, we focused our efforts on recognizing religious paraphernalia, or at least the core symbols that might be mapped onto everyday objects accessible on the island. To be able to “see” common artifacts as ones potentially imbued with religiosity, researchers rely on the context of the artifacts, any modifications to the object or objects, and extensive ethnographic research. Using this process, several artifacts recovered during the 2006 through 2013 field seasons are believed to be associated with African spiritualties.

The majority of these objects are interpreted as charms, literally supernatural objects that provide protection from physical illness, psychological anxiety, or supernatural harm. These charms fall into two categories: personal charms, worn on the body to protect an individual (often on a string around the neck or ankle, or within a cloth charm bag), and house charms, buried to protect an entire home and its inhabitants. Finally, there were a handful of features composed of portions of animals or entire animal carcasses that were likely killed and buried as animal sacrifices, which formed part of a dedication ritual.

The forms of these objects could vary, but examples of likely personal charms once worn on the body include glass beads (mostly blue), a perforated silver coin, a chandelier crystal, and a brass sideplate for a musket, cast in the shape of a dragon and inscribed with an “X” on its back.

The forms of these objects could vary, but examples of likely personal charms once worn on the body include glass beads (mostly blue), a perforated silver coin, a chandelier crystal, and a brass sideplate for a musket, cast in the shape of a dragon and inscribed with an “X” on its back.

House charms were typically buried, and often included iron objects. For example, iron tools, including hoes, a plowshare, and an axe, were placed at the back doorways of four cabins. Another iron object was a padlock with three “Xs” inscribed on its keyhole cover, and buried near the back door of Cabin E-10. Other possible house charms include large lightning whelks buried in the yards of cabins; a water-polished stone that could not naturally exist on this sand and clay island, recovered at the base of a slave water well; and prehistoric stone axes found buried in the floor or yard of cabins E-10 and E-11. Finally, there were lightning whelk shells placed above graves in the Kingsley African Burial Ground, to protect the souls of the recently departed from malevolent forces.[8]

Dedication ceremonies for buildings or other constructions in Central and West African cultures often involved animal sacrifice, and some or all of the animal’s body could be buried. Three examples are known for Kingsley Plantation—a pig skull buried adjacent to the construction pit for the water well behind Cabin E-11; an intact pig carcass, buried beneath the floor of the sugar mill; and a unique discovery, an intact chicken, along with an egg still inside the hen’s body, placed above an iron laterite concretion and a single glass bead, all buried together beneath the floor of Cabin W-15. It is believed to have been placed there when the cabin was initially constructed, just as the Kingsleys and their enslaved population arrived on Fort George Island for the first time in the spring of 1814.[9]

Dedication ceremonies for buildings or other constructions in Central and West African cultures often involved animal sacrifice, and some or all of the animal’s body could be buried. Three examples are known for Kingsley Plantation—a pig skull buried adjacent to the construction pit for the water well behind Cabin E-11; an intact pig carcass, buried beneath the floor of the sugar mill; and a unique discovery, an intact chicken, along with an egg still inside the hen’s body, placed above an iron laterite concretion and a single glass bead, all buried together beneath the floor of Cabin W-15. It is believed to have been placed there when the cabin was initially constructed, just as the Kingsleys and their enslaved population arrived on Fort George Island for the first time in the spring of 1814.[9]

This “chicken sacrifice” is an inarguable material correlate of African religiosity and serves to vindicate Fairbanks’s original 1968 hypothesis regarding Zephaniah Kingsley and his relationship with the plantation’s enslaved people. In sum, all of the artifacts and features discussed here are just small elements of what was a vast hidden cosmology expressed within a multi-ethnic African community on an island in Spanish Florida two centuries ago. The greater implications of these discoveries are complicated, but do suggest a series of pragmatic coping strategies to help assuage the combined traumas of brutal abductions from across a vast ocean, the perpetual violence or its threat that permeated every day of their lives, and the acute anxieties of life and death in a strange land.

Archaeology balances itself between the humanities and the sciences, but in the end, archaeologists are storytellers. In our interpretation of the physical evidence we find through our excavations, archaeologists create narratives, hopefully true narratives, using best practices and following the evidence derived from the material record. In telling these stories, we must recognize that the act of archaeology is also political action. The stories we choose to tell necessarily exclude other stories that we may choose not to tell. Silences in the past are often not true silences, but constructed absences of willful neglect, a purposeful forgetting. The desire to set right the grave misrepresentations of the history of slavery and the greater black experience in this country that were perpetuated throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, helped inspire the earliest efforts of plantation archaeology, and in time, African Diaspora archaeology. The questions we ask of the past, how we interpret a site, and in the process “create” a past—a people’s history—matter, and in the process we can help or hinder those living in our present, or even those not yet born.

James M. Davidson is Associate Professor and Graduate Coordinator of the Department of Anthropology at the University of Florida. A specialist in nineteenth- and twentieth-century historical archaeology, he has published recent articles in the International Journal of Historical Archaeology, the Journal of African Diaspora Archaeology and Heritage, and the Journal of African American History.

[1] Charles E. Orser, Jr., A Historical Archaeology of the Modern World (New York: Plenum Press, 1996).

[2] Charles Fairbanks, “The Kingsley Slave Cabins in Duval County, Florida, 1968.” Conference on Historic Site Archaeology Papers (1974), 7:62–93.

[3] Daniel L. Schafer, Anna Madgigine Jai Kingsley: African Princess, Florida Slave, Plantation Owner (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2003), 1-2; and Daniel W. Stowell, ed., Balancing Evils Judiciously: The Proslavery Writings of Zephaniah Kingsley (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2000), 22–23, 40–41, and 121.

[4] Daniel W. Stowell, Timucuan Ecological and Historical Resource Study (Atlanta: US Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Southeast Field Area, 1996), 40–42 and 45–46; and Schafer, Anna Madgigine Jai Kingsley, 38–46.

[5] Stowell, ed., Balancing Evils Judiciously, 69.

[6] Lydia Maria Child, Letters from New York (1845; repr. Freeport, New York: Books for Libraries Press, 1970), 155.

[7] James M. Davidson, “‘A Cluster of Sacred Symbols’: Interpreting an Act of Animal Sacrifice at Kingsley Plantation, Fort George Island, Florida (1814-1839).” International Journal of Historical Archaeology (2015), 19(1): 76–121.

[8] Davidson, “‘A Cluster of Sacred Symbols’: Interpreting an Act of Animal Sacrifice at Kingsley Plantation,” International Journal of Historical Archaeology, 19(1): 76–121.

[9] Davidson, “‘A Cluster of Sacred Symbols’: Interpreting an Act of Animal Sacrifice at Kingsley Plantation,” International Journal of Historical Archaeology, 19(1): 76–121.