The Great Negro Plot of 1741

by Thomas J. Davis

New York burned thirteen Black men at the stake and hanged another seventeen Black men along with two White men and two White women between May 11 and August 29, 1741. The executions occurred as part of what came to be called “The Great Negro Plot” or “The New York Conspiracy.”

New York burned thirteen Black men at the stake and hanged another seventeen Black men along with two White men and two White women between May 11 and August 29, 1741. The executions occurred as part of what came to be called “The Great Negro Plot” or “The New York Conspiracy.”

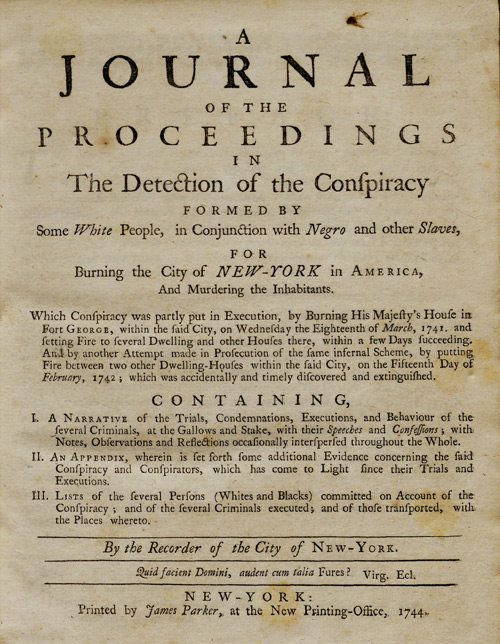

The city commissioned an official record of the episode. New York Provincial Supreme Court of Judicature Justice Daniel Horsmanden compiled the report, published in 1744 as A Journal of the Proceedings in the Detection of the Conspiracy Formed by Some White People, in Conjunction with Negro and Other Slaves, for Burning the City of New-York in America, and Murdering the Inhabitants.

As with most commission reports on urban disturbances involving Blacks in America in the centuries to come, the Journal provoked skepticism and more questions than answers. The episode it recorded, however, laid bare much about law, life, provincial politics, prosecution of crimes, the structure of slavery, class relations, and more in the burgeoning city of 9,000 Whites and 2,000 Blacks crowded on the southern tip of Manhattan Island.

The broad strokes of what happened were clear, as were the conditions in which they developed. Manhattan had the second largest urban slave population in North America, behind only Charleston, South Carolina, and this shaped the episode’s emotive environment. Black men faced rising resentment in the city as their numbers began spiking in the 1730s with their increasing employment as craftsmen. White workingmen complained bitterly about being displaced or undercut by the competition, and they pressed hard to restrict, if not eliminate, such labor. To many, that meant ridding the city as much as possible of Black men, who were often viewed as nothing but troublemakers, whatever work they did. Black women were spared such rancor as they were regarded as luxuries, employed as household drudges for those who could afford them.

The episode’s immediate physical and psychological setting arose in part from the October 1739 outbreak of the War of Jenkins’ Ear in the Caribbean. New Yorkers resented the hostilities as an intrusion of British imperial interests that they viewed as dragging them not only into things they felt were none of their business but into things that in fact hurt their business as it cut trade with their best markets in the West Indies.

In March 1741, city folks were trying to recover from the hardest winter in living memory. Unrelenting snow had started at Christmastime. Frigid temperatures followed. Ice filled the Hudson, then called the North River. Many grew sorely hungry as they huddled with scant provisions as cupboards and markets emptied. Firewood and food, when they could be had, sold for exorbitant prices. The wealthy managed; the middling and poor grumbled. Sullen complaints abounded, and they were about more than the weather.

As the worst of winter ebbed, disaster struck. It started on March 18 when a spectacular blaze engulfed the colonial capital’s administrative center at Fort George. The flames threatened a calamity all city residents feared as their barely five-square-mile warren of wooden structures lay like stacked tinder from the harbor to just beyond Beekman Street, all south of present-day Washington Square. When fire flashed anywhere, it caused alarm everywhere. The 1666 Great Fire of London that razed half the English capital seared the nightmare of an uncontrolled urban blaze into the consciousness of British Atlantic towns like New York City. Within three hours, the blaze claimed all the Fort’s main buildings and killed one soldier, as a gale drove flames to neighboring homes. Mercifully, toward evening, the fickle winds brought heavy rains that dampened the fire’s spread.

The danger seemed contained. But almost exactly a week later fire flared again. And then it struck again a week later, for the third Wednesday in a row. Within days more than a half dozen fresh fires terrified the townspeople.

Few believed the blazes all accidents, and clamor arose for answers, pushing city and provincial officials to account for the causes and to squelch any more outbreaks. But more there were.

Arson was on the minds of many, and concerns were voiced when smoke from a fire obviously set in the roof shingles of a house in an already scorched street fixed suspicion on Juan de la Sylva. Captured among the crew of the sloop La Soledad, taken as a prize of war in mid-1740, and sold in the city as a slave along with his dark-skinned mates while the white-complexioned were held as prisoners of war, Juan had a reputation for surliness. Neighbors dragged him to jail and raised a hue and cry to “take up the Spanish negroes.”

But the day’s danger was hardly over.

A major blaze threatened the waterfront warehouses. Just about when it was under control, another alarm sounded—the fourth that day. Spotting a Black man fleeing the scene, a firefighter yelled “a negro, a negro!” Fraught with weeks of anxiety, some amplified the cry to “the negroes are rising, the negroes are rising!”

There was no containing the hotheaded. Mobs grabbed any Black man at hand, jailing at least two hundred that day, April 6. On that date in 1712, Blacks in New York City had set a fire in the night and pounced upon first responders, killing nine White men and wounding at least a dozen others. Punishing fire with fire, New York had burned twenty Blacks at the stake after trial and conviction.

The memory of 1712 lingered in 1741 as five months of investigations, prosecutions, and executions began. Almost all Black males older than sixteen came in for questioning—from Mayor John Cruger’s Deptford to Chief Justice James DeLancey’s Othello to former alderman Johannes Roosevelt’s Quack. (Roosevelt was a forebear of the Oyster Bay Roosevelts, Teddy and Eleanor.)

Some Blacks stubbornly said little or nothing. But over the weeks many talked, saying whatever they thought would spare them. Some of what was said explained the blazes. Quack admitted to starting the fire at the Fort, for example, enraged that Acting Governor George Clarke forbade Quack from visiting his wife, the enslaved cook at the governor’s house. Like most enslaved couples in the city, Quack and his wife lived in separate households as they were held by different slaveholders.

What officials called “confessions” shocked Whites who had no notion of what Blacks felt and thought. Learning what Blacks did outside of working hours and, especially, what they did at night—gathering illegally, grumbling against slavery and their individual slaveholders, organizing crime, and doing their own deals to ease their lives as best they could—had Whites aghast.

Prosecutors bundled the confessions into one grand conspiracy. That singular vision projected the city as a smoldering ruin, its valuables looted, its White men slaughtered, its White women ravished, and its enslaved people gleefully sailing away to French or Spanish arms.

The ugly image played on popular prejudices. It depicted Blacks as naturally corrupt, dangerously untrustworthy, and easily led into mischief and treachery; the Spanish and French as devious minions of a popish plot for worldwide Catholic dominion; and Whites who fraternized with Blacks as perverted enemies of their own race, lured by ill-gotten gains and prurient desires. Since Blacks were believed by Whites to have limited intelligence, the two White men sentenced to hang were cast as masterminds. The episode saw thirty-four people executed and seventy-two Blacks banished from the province, and portended many challenges ahead for New York City.

Further Reading

Davis, Thomas J. A Rumor of Revolt: The “Great Negro Plot” in Colonial New York. New York: Free Press/Macmillan, 1985. Paperback ed. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1990.

Davis, Thomas J. “The Great Negro Plot in New York.” True Stories from the American Past, vol. 1: To 1865 , eds. Altina L. Waller and William Graebner, 77–89. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1997.

Davis, Thomas J. “These Enemies of Their Own Household: A Note on the Troublesome Slave Population in Eighteenth Century New York,” Journal of the Afro-American Historical and Genealogical Society 5 (1984): 133–148.

Davis, Thomas J. “New York’s Long Black Line: A Note on the Growing Slave Population, 1626–1790,” Afro-Americans in New York Life and History 2 (January 1978): 41–59.

Davis, Thomas J. “The New York Slave Conspiracy of 1741 as Black Protest,” Journal of Negro History 56 (January 1971): 17–30.

Horsmanden, Daniel. The New York Conspiracy, ed. with an introduction by Thomas J. Davis. Boston: Beacon Press, 1971.

Lepore, Jill. New York Burning: Liberty, Slavery, and Conspiracy in Eighteenth-Century Manhattan. New York: Vintage, 2009.

Thomas J. Davis, PhD, JD, is professor of history emeritus at Arizona State University, Tempe. He is the editor of the official 1744 Journal of the Proceedings (1971) and author of A Rumor of Revolt: The “Great Negro Plot” in Colonial New York (1985), Race Relations in America (2006), and History of African Americans: Exploring Diverse Roots (2016), among other works. From 1993 to 2006 he was expert advisor and consultant to the Federal Steering Committee on the African Burial Ground that produced the US National Park Service African Burial Ground National Monument in lower Manhattan.