Freedom, Slavery, and War in Virginia

by Alan Taylor

In July 1807, a fourteen-year-old named Willis escaped from his master in Virginia’s Princess Anne County. In a stolen boat, he rowed out to a British warship, where Willis expected a warm welcome, because war seemed imminent between the United States and the British Empire. Eager for information about the Americans, the Royal Navy captain took in, fed, and clothed Willis and four other fugitives. A month later, however, the captain sent them back to their masters in a bid to defuse tensions with the Americans. Instead of dwelling on that betrayal, Willis later recalled that “he had been to the British once & that they treated him well & he wished his master had let him remain.” In 1814, after war did erupt, Willis had better luck, fleeing again to a British warship along with “many other negroes in the neighbourhood.” As potential liberators, the British appealed to the enslaved people living around Chesapeake Bay.[1]

In July 1807, a fourteen-year-old named Willis escaped from his master in Virginia’s Princess Anne County. In a stolen boat, he rowed out to a British warship, where Willis expected a warm welcome, because war seemed imminent between the United States and the British Empire. Eager for information about the Americans, the Royal Navy captain took in, fed, and clothed Willis and four other fugitives. A month later, however, the captain sent them back to their masters in a bid to defuse tensions with the Americans. Instead of dwelling on that betrayal, Willis later recalled that “he had been to the British once & that they treated him well & he wished his master had let him remain.” In 1814, after war did erupt, Willis had better luck, fleeing again to a British warship along with “many other negroes in the neighbourhood.” As potential liberators, the British appealed to the enslaved people living around Chesapeake Bay.[1]

In June 1812, the United States declared war on the British Empire and invaded Canada, then part of that empire. Counterattacking, the British sent warships into Chesapeake Bay to attack ships, farms, and villages in Maryland and Virginia. The Royal Navy commanders hoped to force Americans to pull back their troops invading Canada and to negotiate peace.[2]

During 1813, the British rarely ventured far from the shore into the interior, a mix of forests and fields, from a dread of ambushes by the Americans. That limited range of attacks kept the British from inflicting a crippling blow on their enemy. The Royal Navy also suffered losses of manpower as many sailors and marines deserted, running away to join the Americans, who offered better pay and conditions. Employing the term “Jack,” the nickname for a common sailor, a British naval lieutenant, James Scott, complained, “The captivating sounds of liberty and equality . . . have led astray many a clearer head and sounder judgment than falls to the lot of poor Jack.” A Royal Marine officer pursued four deserters, but they escaped to shore, where, he reported, “the four villains tossed their hats up, saying they were now Americans.” In the Chesapeake, British commanders had to guard their own men while fighting the enemy.[3]

The British saw solutions to their problems in the thousands of people held in slavery on the farms and plantations around the bay. Stealing boats and canoes, the runaways sought freedom and to take revenge on their masters by joining the British. Unlike so many British sailors and marines, the runaways wanted to stay with the Royal Navy. Admiral George Cockburn welcomed Black recruits: “They are stronger Men and more trust worthy for we are sure they will not desert whereas I am sorry to say we have Many Instances of our [White] Marines walking over to the Enemy.” Promoting escapes seemed the perfect way to strengthen the British force and to punish Americans for encouraging desertion from the Royal Navy.[4]

The runaways also brought invaluable local knowledge of waterways and paths through the woods. As guides and recruits, the formerly enslaved people could guide raiders away from ambushes to find farms and plantations rich in the cattle, pigs, and flour that the British needed to supply their sailors and marines. At those farms and plantations, they could also recruit more Blacks to escape from slavery by joining the British. Every raid strengthened the British as it weakened the Americans, who lost enslaved people essential to their economy.

At first, the Royal Navy captains felt restricted by orders from their government in London to welcome only a few runaway men who could prove useful as guides. That government wanted to avoid the high cost of supplying thousands of runaways including women and children. But entire families came, forcing naval captains to fudge their restrictive orders. In September 1813, a British admiral reported, “I could not refuse those which have got on board the ships in Canoes—men, women & children—amounting to about 300 as they would certainly have been sacrificed if they had been given up to their masters & destroyed our Influence among them, for at present every Slave in the Southern States would join us if they could get away.” By the end of 1813, at least six hundred runaways in the Chesapeake had escaped to the British. They forced a shift in British policy in favor of welcoming and enlisting formerly enslaved men as the best way to attack the southern states.[5]

In return for military help, the British offered freedom, clothing, pay, and land after the war in a British colony. The government preferred to welcome only men, but naval captains explained that few Black men would enlist without a safe haven for their families. Bowing to that reality, the British government recognized that “the Assistance given to their families in the British Service [was] understood to be one principal Cause of the desire to emigrate, which had been manifested by the Negro population.”[6]

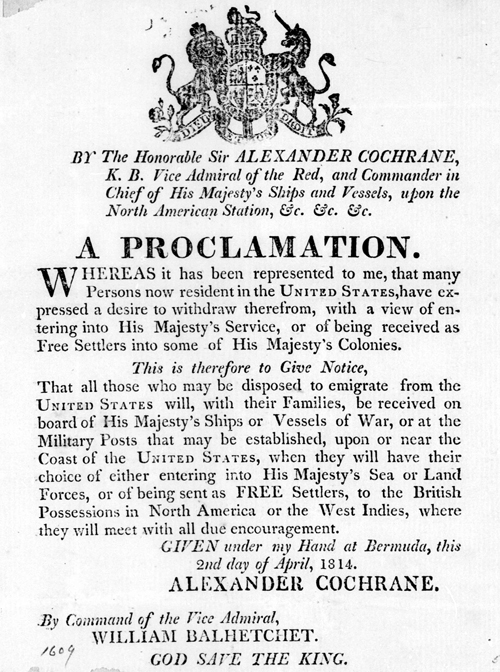

Admiral Sir Alexander Cochrane welcomed the shift in policy. During a pre-war visit to Virginia, Cochrane had concluded “from what I saw of its Black Population they are British in their hearts and might be made of great use if War should be prosecuted with Vigor.” In 1814, he ordered his captains to make liberating Blacks the prime goal of their shore raids: “Let the Landings you may make be more for the protection of the desertion of the Black Population than with a view to any other advantage. . . . The great point to be attained is the cordial Support of the Black population.” The new policy paid off. About 2,800 runaways joined the British during 1814, more than four times as many as in 1813.[7]

In April 1814, to accommodate the refugees, Cochrane’s chief subordinate, Rear Admiral Cockburn, occupied and fortified Tangier Island, within Chesapeake Bay and twenty miles from Virginia’s Eastern Shore. It seemed far enough from the mainland to discourage White marines from deserting, but close enough to entice refugees. On the southern end of the island, where sea breezes kept the mosquitoes at bay, the British built Fort Albion, bristling with cannon and featuring a hospital, church, and barracks for the troops and cabins for the refugees.[8]

When refugee men reached a warship or Tangier Island, they had the choice of enlisting as sailors or marines or of working to build barracks and fortifications on the island. As with the Black regiments of the Union Army during the Civil War, White men served as the officers in the marine battalion that enlisted Blacks from the Chesapeake. In addition to providing the rank-and-file privates, Blacks served as the corporals and sergeants. Women provided essential services as laundresses, nurses, cooks, and guides for raiding parties. Some of the refugees moved on to work at the British naval base at Bermuda, a cluster of islands off the American coast.[9]

Possessing racial prejudices, Cockburn doubted that the refugees would make good marines, but he soon changed his mind. After watching them train for a month, he reported that they were “getting on astonishingly and are really very fine Fellows. . . . They have induced me to alter the bad opinion I had of the whole of their Race & I now really believe these we are training, will neither shew want of Zeal or Courage when employed by us in attacking their old Masters.” With glee, he noted that the Black marines excited “the most general & undisguised alarm” among the Virginians, who expected the formerly enslaved men would “have no mercy on them and they know that he understands bush fighting and the locality of the Woods as well as themselves, and can perhaps play at hide & seek in them even better.” Indeed, the Black marines became the best fighters in the British service along the Chesapeake. Captain Robert Barrie reported that they had “conducted themselves with the utmost Order, Forbearance, and Regularity.”[10]

Thanks to Black guides, raids could push deeper into the countryside, evading ambushes to find hidden herds of livestock on farms. Experienced at dodging slave patrols, enslaved people had developed an intimate, local knowledge of the intricate Tidewater landscape of swamps, forests, and waterways. A British naval lieutenant, James Scott, recalled, “The opportunities afforded us of safely traversing the enemy’s country at night, by means of these black guides, placed a powerful weapon in the Rear-Admiral’s hands. . . . The country within ten miles of the shore lay completely at our mercy.” An American general complained, “Our negroes are flocking to the enemy from all quarters, which they convert into troops, vindictive and rapacious—with a most minute knowledge of every bye path. They leave us as spies upon our posts and our strength, and they return upon us as guides and soldiers and incendiaries.” By converting enslaved men into marines, the British grew stronger while the American economy became weaker.[11]

During the summer of 1814, Admiral Cockburn targeted the shores of southern Maryland and Virginia’s Northern Neck. While seeking supplies and more Black recruits, the British broke military resistance along the Potomac and Patuxent Rivers. In mid-August, a local planter complained that the British felt so secure that, after marching unmolested deep into St. Mary’s County, the officers “amused themselves at nine pins for an hour or two” before returning to their ships.[12]

Cockburn sought to open the way for the British to ascend the Potomac and Patuxent Rivers to attack Washington, DC. Cockburn wanted to discredit President James Madison as incompetent to defend even the nation’s capital. Having eliminated militia resistance along the Patuxent, British troops and Black marines landed without resistance on August 19–20 and quickly moved upriver, forcing the Americans to destroy their gunboats. On August 24, the invaders overwhelmed a militia force at Bladensburg, an eastern suburb of Washington. Fear of a slave revolt accelerated the militia flight. General Walter Smith of the District militia recalled “that each man more feared the enemy he had left behind, in the shape of a slave in his own house or plantation, than he did anything else.” The victors then swept into the city to destroy the public buildings, including the White House and Capitol. At sunset on August 25, after twenty-four destructive hours in the city, the British marched away, returning without opposition to their warships on the Patuxent.[13]

With the help of Black marines, the invaders inflicted the greatest defeat suffered by Americans during the War of 1812. By their courage, persistence, and numbers, runaways had changed British policy, which enabled Admiral Cockburn to adopt a more aggressive strategy for 1814. Black guides and marines had been essential to the summer raids that had opened Washington to attack in August. In Virginia’s Northern Neck, General Hungerford complained of “the great advantage the Enemy have over us in being informed by our Blacks of all our movements.” Black initiative transformed the British conduct of the war in the Chesapeake. This performance strengthened abolitionist arguments within the United States that internal security required greater moral consistency by Americans. By freeing people from slavery, the United States could benefit from Blacks fighting for the cause of freedom.[14]

Alan Taylor is Thomas Jefferson Foundation Chair in American History at the University of Virginia. His publications include William Cooper’s Town: Power and Persuasion on the Frontier of the Early American Republic (Knopf, 1995), The Divided Ground: Indians, Settlers, and the Northern Borderland of the American Revolution (Knopf, 2006), and The Internal Enemy: Slavery and War in Virginia: 1772–1832 (Norton, 2014), which won the 2014 Pulitzer Prize for History.

NOTES

This essay adapts and condenses material previously published in chapters six and nine of Alan Taylor, The Internal Enemy: Slavery and War in Virginia, 1772–1832 (New York: W. W. Norton, 2014).

[1] Depositions of Cornelius Matthias, May 5, 1823, and David Shirley, May 5, 1823 (all quotations), Auditor of Public Accounts, General Militia Records: List of Furloughs & Discharges, entry 258, box 779, Library of Virginia (Richmond).

[2] John W. Croker to Sir John Borlase Warren, January 9, 1813, and Warren to Croker, March 28, 1813, in William S. Dudley, ed., The Naval War of 1812: A Documentary History, 3 vols. (Washington, DC: Department of the Navy, 1992), vol. 2:14, and 80–81; Andrew Lambert, The Challenge: America, Britain, and the War of 1812 (London: Faber and Faber, 2012), 64, 109–12, 243.

[3] James Scott, Recollections of a Naval Life, 3 vols. (London: Brichard Bentley, 1834), vol. 2:14 (“captivating sounds”); Anne Petrides and Jonathan Downs, eds., Sea Soldier: An Officer of Marines with Duncan, Nelson, Collingwood, and Cockburn, The Letters and Journals of Major T. Marmaduke Wybourn, RM, 1797–1813 (Tunbridge Wells, UK: Parapress, 2000), 181–82 (“four villains”).

[4] C. J. Bartlett and Gena A. Smith, “‘A Species of Milito-Nautico-Guerilla Warfare’: Admiral Alexander Cochrane’s Naval Campaign against the United States, 1814–1815,” in Julie Flavell and Stephen Conway, eds., Britain and America Go to War: The Impact of War and Warfare in Anglo-America, 1754 –1815 (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2004): 179; George Cockburn to Sir Alexander Cochrane, June 25, 1814 (“stronger men”), in W. S. Dudley, ed., The Naval War of 1812, vol. 3:116; Scott, Recollections, vol. 3:216.

[5] Bartlett and Smith, “‘Species of Milito-Nautico-Guerilla Warfare,’” 187; Sir John Borlase Warren to Lord Melville, September 6, 1813, MG 24, F 132, reel A-2076, Library and Archives Canada (Ottawa).

[6] Joseph Nourse to George Cockburn, July 23, 1814, in W. S. Dudley, ed., The Naval War of 1812, vol. 3: 159; Henry Bathurst to Robert Ross, August 10, 1814 (“assistance”), and Bathurst to Sir Alexander Cochrane, October 26, 1814, Sir Alexander Cochrane Papers, reel 1, Library of Congress.

[7] Sir Alexander Cochrane, “Thoughts on American War,” April 27, 1812 (“from what I saw”), Henry Dundas, Viscount Melville, Papers, Huntington Library (San Marino, CA); Cochrane to George Cockburn, July 1, 1814 (“Let the Landings”), in W. S. Dudley, ed., The Naval War of 1812, vol. 3:130.

[8] George Cockburn to Sir Alexander Cochrane, April 2, 1814, and April 13, 1814, in W. S. Dudley, ed., The Naval War of 1812, vol. 3:43 and 47.

[9] George Cockburn to Sir Alexander Cochrane, May 9, 1814, in W. S. Dudley, ed., The Naval War of 1812, vol. 3:62; William Stanhope Lovell, Personal Narrative of Events from 1799 to 1815 (London: William Allen & Co., 1879), 153.

[10] George Cockburn to Sir Alexander Cochrane, April 2, 1814 (“most certainly”), Cockburn to Sir John Borlase Warren, April 13, 1814, Cockburn to Cochrane, May 10, 1814, and Robert Barrie to Cockburn, June 19, 1814, in W. S. Dudley, ed., The Naval War of 1812, vol. 3:43–44, 47, 65–66, and 111–14.

[11] George Cockburn to Sir Alexander Cochrane, April 2, 1814, in W. S. Dudley, ed., The Naval War of 1812, vol. 3:43–45; Scott, Recollections, vol. 3: 120–21 (“opportunities”); John P. Hungerford to the Adjutant General, August 5, 1814 (“Our negroes”), in H. W. Flournoy, ed., Calendar of Virginia State Papers and Other Manuscripts (New York: Kraus Reprint Corporation, 1968, of Richmond 1890 original), vol. 10:368.

[12] Scott, Recollections, vol. 3:229; Robert Barrie to George Cockburn, June 19, 1814, in W. S. Dudley, ed., The Naval War of 1812, vol. 3:111–13; John Rousby Plater to Levin Winder, August 15, 1814 (“nine pins”), Maryland State Papers, ser. A, box S1004–130, doc. 3, Maryland State Archives (Annapolis).

[13] Scott, Recollections, vol. 3:239; George Cockburn to Sir Alexander Cochrane, July 31, 1814, in W. S. Dudley, ed., The Naval War of 1812, vol. 3:168; Walter Smith quoted in Benson J. Lossing, Pictorial Field Book of the War of 1812 (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1869), 938 (“each man”).

[14] John P. Hungerford to James Barbour, July 21, 1814 (“great advantage”), in Flournoy, ed., Calendar of Virginia State Papers, vol. 10:362.