Fighting for Democracy in World War I—Overseas and Over Here

by Maurice Jackson

Maurice Jackson is Associate Professor of History and African American Studies at Georgetown University. He is the author of Let This Voice Be Heard: Anthony Benezet, Father of Atlantic Abolitionism (2009), and the co-editor of African Americans and the Haitian Revolution (2009) and Quakers and Their Allies in the Abolitionist Cause, 1754–1808 (2015). His most recent book is DC Jazz: Stories of Jazz Music in Washington, DC, co-edited with Blair A. Ruble (2018).

The United States invaded Haiti, its southern neighbor, in 1915—effectively making it a US protectorate—citing concern over the influence of Germany and France, the financial and political instability of the country, and the "safety" of the newly opened Panama Canal. Yet as war loomed over Europe the US did not declare war with Germany right away, first breaking diplomatic relations on February 3, 1917. On April 2, 1917, President Wilson went before a joint session of Congress to request that war be declared. The Senate voted on April 4 and the House on April 6 to support his appeal.

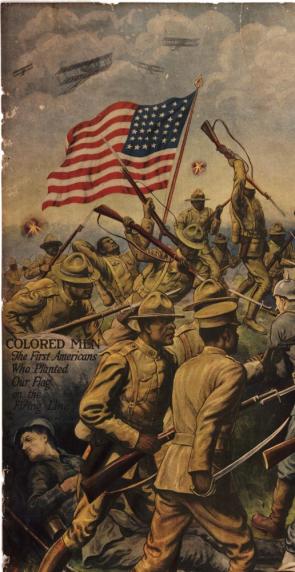

War plans had been in the making, and "more than a month before the United States declared war, the First Separate Battalion (Colored) of the Washington, D.C., National Guard was mustered into federal service." [1] The regiment had at first been assigned to guard the buildings of the Federal Enclave, including the "White House, the Capitol, and other federal buildings, and facilities such as bridges and water supply, against possible enemy sabotage."[2] A source of pride to blacks in Washington, there was white resistance to the battalion’s mobilization and deployment overseas. None was more verbal than Kentucky congressman Robert Y. Thomas, who said, "I know that a n—— knows nothing about patriotism, love of country, or morality . . . they are going to make trouble wherever they go."[3] Racist propaganda insisted that blacks could never be men of valor and were not to be trusted on the battlefield. Yet as the war preparations continued, black troops were needed and proved invaluable, just as in the Civil War.

War plans had been in the making, and "more than a month before the United States declared war, the First Separate Battalion (Colored) of the Washington, D.C., National Guard was mustered into federal service." [1] The regiment had at first been assigned to guard the buildings of the Federal Enclave, including the "White House, the Capitol, and other federal buildings, and facilities such as bridges and water supply, against possible enemy sabotage."[2] A source of pride to blacks in Washington, there was white resistance to the battalion’s mobilization and deployment overseas. None was more verbal than Kentucky congressman Robert Y. Thomas, who said, "I know that a n—— knows nothing about patriotism, love of country, or morality . . . they are going to make trouble wherever they go."[3] Racist propaganda insisted that blacks could never be men of valor and were not to be trusted on the battlefield. Yet as the war preparations continued, black troops were needed and proved invaluable, just as in the Civil War.

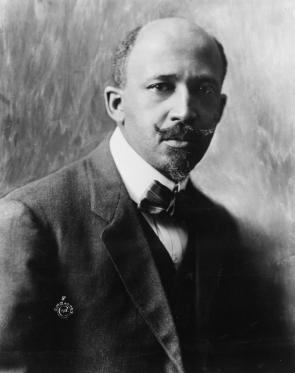

Soon W. E. B. Du Bois caused a stir with his "Close Ranks" essay published in The Crisis in July 1918. The second paragraph of the essay reads:

We of the colored race have no ordinary interest in the outcome. That which the German power represents today spells death to the aspirations of Negroes and all darker races for equality, freedom and democracy. Let us not hesitate. Let us, while this war lasts, forget our special grievances and close our ranks shoulder to shoulder with our own white fellow citizens and the allied nations that are fighting for democracy. We make no ordinary sacrifice, but we make it gladly and willingly with our eyes lifted to the hills.[4]

Immediately the black press, including Du Bois’s allies, took up verbal arms against his seeming acquiescence. The Pittsburgh Courier editorial was swift and cutting: "The learned Dr. Du Bois has seldom packed more error into a single sentence."[5]

Immediately the black press, including Du Bois’s allies, took up verbal arms against his seeming acquiescence. The Pittsburgh Courier editorial was swift and cutting: "The learned Dr. Du Bois has seldom packed more error into a single sentence."[5]

Chad L. Williams has pointed out that "the War Department implicitly acknowledged the military and political impossibility of assigning every African American draftee for labor duties and thus began floating various ideas for establishing combat units composed of black men procured through the Selective Service System."[6] Emmett J. Scott was assigned to be the Special Adjutant to the Secretary of War Newton D. Baker.[7] As Baker’s confidential adviser, Scott held "the highest government position ever achieved by a Black."[8] Scott wrote that blacks should not view him as being able to "effectively abolish overnight all racial discriminations and injustices."[9] He could not.

African Americans were organized into four regiments under the 93rd infantry division. The four units were the 369th (New York, already sent to France), the 370th (Illinois, which had black officers), the 371st (draftees), and the 372nd. The 372nd regiment was composed of six National Guard units from Washington DC, and the First Battalion Companies A-D, from Maryland, Tennessee, Massachusetts, Ohio, and Connecticut. At first two of the three battalions were led by black officers, but that quickly changed by order of Secretary of War Baker.[10] ![Charles Young, ca. 1919 (<i />History of the American Negro in the Great World War by William Allison Sweeney [Chicago: G. G. Sapp], 1919) Charles Young, ca. 1919 (History of the American Negro in the Great World War by William Allison Sweeney [Chicago: G. G. Sapp], 1919)](/sites/default/files/essay-images/charles.young_.1919.jpg) The 372nd was first led by a notoriously bigoted white officer, Colonel Glendie Young, instead of its ranking African American, Charles Young, who Du Bois had hoped "might be given his chance here but nothing came of this."[11] Although racially insensitive officers led the regular Army, the National Guard unit’s leadership, which was led under individual state authority, was far worse.

The 372nd was first led by a notoriously bigoted white officer, Colonel Glendie Young, instead of its ranking African American, Charles Young, who Du Bois had hoped "might be given his chance here but nothing came of this."[11] Although racially insensitive officers led the regular Army, the National Guard unit’s leadership, which was led under individual state authority, was far worse.

According to Gail Buckley, "by July 5, 1917, more than 700,000 blacks were registered; less than 10% of the U.S. population, they made up 13% of all U.S. draftees. Of the 367,000 black draftees who ultimately served, 89% were assigned to labor, supply, and service units. Only 11 percent of all black military forces would see combat—the National Guard, and a few southern draftee units."[12] Gerald Astor writes that of the "404,308 African Americans in the Army . . . around 42,000 could be listed as combat soldiers with 90 percent of them serving in the two infantry divisions."[13] By January 1919, most had been assigned to segregated units and about 20 percent fought in two specially created all-black combat units.

About 160,000 of the 200,000 blacks sent to France served in SOS [service] units. Roughly 20 percent of the black soldiers or about 40,000 men who were in combat were in the 92nd and 93rd Infantry Divisions. The 372nd division was sent to Alsace, where they fought with the 157th French Division. The men of the 372nd were led by senior white and junior black officers. They arrived in France in early summer of 1918 and joined the French 157th Red Hand Division.[14] The French commanding general paid tribute, stating "[t]he ‘Red Hand’ sign of the Division, thanks to you [black soldiers], became a bloody hand . . . You have well avenged our glorious dead."[15]

As African Americans began to arrive on French shores in 1918, most under British or French command, they were exploited and often degraded by white officers. For some, "the French experience became decisive in the development of a new sense of solidarity," among themselves and some of the African units.[16] The French people did not have the problems that the American whites had in recognizing the heroics of black Americans. Some white officers were able to overcome the racism. Said one: "I’d take my chance of going anywhere with these black soldiers at my back. So would any of the rest of the officers."[17] In total, during the war the 93rd Division suffered 584 men killed and 2,852 wounded.[18] Of the 400,000 black soldiers, about "20 percent served in combat roles."[19] The men of the 372nd suffered more than 600 casualties. The French government awarded the regiment the Croix de Guerre with Palm. Three of its officers were honored with the French Legion of Honor, 123 men personally won the Croix de Guerre, and twenty-six were awarded the Distinguished Service Cross.[20] The "First Separate Battalion" also received the Croix de Guerre.[21]

The most famous unit was the 369th Infantry known as the Harlem Hellfighters because they were a New York African American regiment. The US Army would not allow them to serve alongside white soldiers, so they were merged into the French military and were supplied with French supplies, were based in French camps, and fought in France. Many are buried near the Argonne Forests and others near the trenches of Aisne-Marne. Black soldiers had longed to go home from the war and some sang the verses:

I ain’t got no business in Germany

And I don’t want to go to France

Lawd, I want to go home, I want to go home.[22]

Some returning soldiers later were lynched while still in their military uniforms. Sadly it was not until June 2, 2015—when President Barack Obama posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor to Private Henry Johnson, a member of the famed Harlem Hellfighters—that those African Americans who served received due recognition for their service.[23] One of Johnson’s compatriots said of the French appreciation of Johnson and his fellow Bronze fighters,

Some returning soldiers later were lynched while still in their military uniforms. Sadly it was not until June 2, 2015—when President Barack Obama posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor to Private Henry Johnson, a member of the famed Harlem Hellfighters—that those African Americans who served received due recognition for their service.[23] One of Johnson’s compatriots said of the French appreciation of Johnson and his fellow Bronze fighters,

France has wept over them—wept the tears of gratitude and love. France had sung and danced and cried to their music. France had given its first war medal for an American private to one of their number. France had given them the collective citation of flying the Croix de Guerre streamers at the peak of its colors. France had kissed those colored soldiers—kissed them with reverence and in honor, first upon the right cheek and then upon the left.[24]

Other soldiers came home with renewed hope, military discipline, and knowledge of weapons. W. E. B. Du Bois wrote of their bravery in war, and of the racism they came home to, in his article "Returning Soldiers":

We return.

We return from fighting.

We return fighting.

Make way for Democracy! We saved it in France, and by the Great Jehovah, we will save it in the United States of America, or know the reason why.[25]

[1] Arthur E. Barbeau and Florette Henri, The Unknown Soldiers: Black American Troops in World War I (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1974), 19.

[2] Barbeau and Henri, The Unknown Soldiers, 19–20.

[3] Quoted in Barbeau and Henri, The Unknown Soldiers, 78.

[4] W. E. B. Du Bois, "Close Ranks," in David Levering Lewis, ed., W. E. B. Du Bois: A Reader (New York: Henry Holt and Co., 1995), 697.

[5] Pittsburgh Courier, July 20, 1918, quoted in David Levering Lewis, W. E. B. Du Bois: Biography of a Race, 1868–1919 (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1994), 556.

[6] Chad L. Williams, Torchbearers of Democracy: African American Soldiers in the World War I Era (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010), 67.

[7] Emmett J. Scott, "The Participation of Negroes in World War I: An Introductory Statement," Journal of Negro Education 12 (1943), 288–297.

[8] Gail Buckley, American Patriots: The Story of Blacks in the Military from the Revolution to Desert Storm (New York: Random House, 2001), 178–179.

[9] Emmett J. Scott, Official History of the American Negro in the World War (1919), quoted in Buckley, American Patriots, 179.

[10] Barbeau and Henri, The Unknown Soldiers, 79.

[11] W. E. B. Du Bois, "An Essay toward a History of the Black Man in the Great War" in Lewis, ed., W. E. B. Du Bois: A Reader, 711.

[12] Buckley, American Patriots, 165.

[13] Gerald Astor, The Right to Fight: A History of African Americans in the Military (Novato CA: Presidio Press, 1998), 110.

[14] Lt. Col. [Ret.] Michael Lee Lanning, The African-American Soldier: From Crispus Attucks to Colin Powell (Secaucus NJ: Carol Publishing Group, 1999), 145.

[15] The Record of the 372nd, Chapter XVII, http://net.lib.byu.edu/estu/wwi/comment/scott/SCh17.htm. In French units there were about 500,000 African soldiers. While Africans who fought for France were given French citizenship, black Americans were not even given equal American citizenship.

[16] Dick van Galen Last with Ralf Futselaar, Black Shame: African Soldiers in Europe, 1914–1922 (London: Bloomsbury, 2015), 84.

[17] Quoted in Chester D. Heywood, Negro Combat Troops in the World War (Worcester MA: Commonwealth Press, 1928), 10.

[18] Monroe Mason and Arthur Furr, The American Negro with the Red Hand of France (Boston: Cornwill, 1920), 43–44. Upon arriving in France, the 372nd Infantry was immediately assigned to the 157th Infantry of the French Army—the renowned Red Hand Division—to help fight in the famous Meuse-Argonne offensive.

[19] Jeffrey B. Ferguson, The Harlem Renaissance: A Brief History with Documents (Boston: Bedford/ St. Martin’s, 2008), 5.

[20] Jami Bryan, "Fighting for Respect: African-American Soldiers in WWI" (2003), http://www.militaryhistoryonline.com/wwi/articles/fightingforrespect.aspx.

[21] Barbeau and Henri, The Unknown Soldiers, 131.

[22] James Weldon Johnson, Black Manhattan (1930; repr. New York, 1968), 232–233; Barbeau and Henri, Unknown Soldiers, 204.

[23] See Michael E. Ruane, "Harlem Hellfighters: In WWI, we were good enough to go anyplace," Washington Post, June 1, 2015, and Sarah Kaplan, "WWI ‘Harlem Hellfighter,’ relegated by racism, to receive Medal of Honor," Washington Post, May 15, 2015. The campaign to honor Henry Johnson was led by US senator Charles E. Schumer (D-New York). On May 5, 2015, Senator Schumer issued a press release entitled "An American Hero Will Finally Get the Medal He Deserves."

[24] Quoted in van Galen Last and Futselaar, Black Shame, 85.

[25] W. E. B. Du Bois, "Returning Soldiers," The Crisis 18 (May 1919): 13–14.