The Development of Slavery in the Early Modern Atlantic World

by Michael Guasco

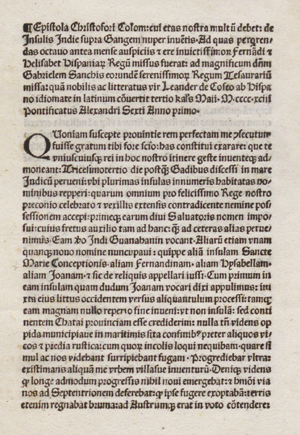

Racial slavery is as old as the Atlantic world itself. As early as the 1440s, a Portuguese expedition returned from West Africa with a small cargo of Africans who had been taken against their will to serve the material interests of European invaders. A half century later, Christopher Columbus would inaugurate the transatlantic slave trade on his second voyage when he kidnapped hundreds of native West Indians and transported them as captives across the ocean to feed the greedy appetites of his Spanish sponsors. Soon thereafter, enslaved Africans and African-descended men and women would find themselves on board Spanish and Portuguese ships bound for the Americas. The commodification of non-European human beings was both a driving force and tragic result of the craven desire of Christian Europeans for wealth and power in the early modern Atlantic world.

Racial slavery is as old as the Atlantic world itself. As early as the 1440s, a Portuguese expedition returned from West Africa with a small cargo of Africans who had been taken against their will to serve the material interests of European invaders. A half century later, Christopher Columbus would inaugurate the transatlantic slave trade on his second voyage when he kidnapped hundreds of native West Indians and transported them as captives across the ocean to feed the greedy appetites of his Spanish sponsors. Soon thereafter, enslaved Africans and African-descended men and women would find themselves on board Spanish and Portuguese ships bound for the Americas. The commodification of non-European human beings was both a driving force and tragic result of the craven desire of Christian Europeans for wealth and power in the early modern Atlantic world.

Throughout history and across the world, slavery has been ubiquitous. During the early modern era (ca. 1450–1650), however, slavery changed in two important ways. First, slavery was increasingly rationalized by rapidly escalating labor demands that were themselves a product of cash-crop agriculture. In previous eras and in other places, slavery had typically been a secondary consideration, a by-product of things like regional warfare or domestic legal systems. In the early modern era, however, the growth of slavery was tied to consumer demand for both labor and the products those laborers cultivated.

Second, slavery in the early modern era was tied to race. It had once been possible for virtually anyone to fall into a state of slavery simply because they were on the losing end of things or because they had done something to deserve the fate. Slavery was punishment. In the early modern Atlantic world, however, enslavers targeted specific groups of people because of their race and rationalized their actions by relying on the logic of racism. Racism provided cover for Europeans to exploit innocent human beings without any legally accepted justification for doing so.

Slavery developed along parallel lines in the early modern era. Native peoples throughout the Americas were the earliest targets for enslavement by the Spanish and Portuguese. In part, capturing and enslaving Indians was simply a money-making scheme for slave traders. But Indian slavery also thrived because of the growing need for labor for the extraction of mineral wealth (gold and silver) and the cultivation of the soil. By one measure, perhaps as many as 2.5 million Indians were enslaved in the Americas before 1650. Certainly, Indian slavery was closely related to some Old World ideas about what to do with the victims of a “just war,” but the practice of capturing, transporting, and exploiting Native peoples was primarily driven by the profit motive at the heart of Iberian colonialism.

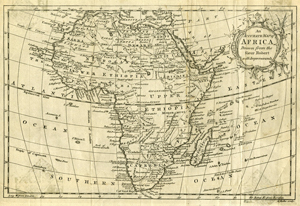

The use of, and trade in, African slaves was different. The horrors of the transatlantic slave trade provide some of the most graphic images of human suffering resulting from the commodification of human beings to fuel plantation empires. While it peaked during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the slave trade was critical to the growth of Atlantic empires from an early date. Even before 1650, perhaps one million people were ripped out of their homes in Africa to serve European masters in the Caribbean and South and North America. Many people died as a result. Of the million or so people who were taken up against their will, one in four did not make it to the other side of the ocean.

The use of, and trade in, African slaves was different. The horrors of the transatlantic slave trade provide some of the most graphic images of human suffering resulting from the commodification of human beings to fuel plantation empires. While it peaked during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the slave trade was critical to the growth of Atlantic empires from an early date. Even before 1650, perhaps one million people were ripped out of their homes in Africa to serve European masters in the Caribbean and South and North America. Many people died as a result. Of the million or so people who were taken up against their will, one in four did not make it to the other side of the ocean.

Ultimately, there was nothing surprising about Spain and Portugal engaging in slavery. Although the transatlantic model and the increasingly predatory stance toward sub-Saharan Africans was new, slavery had long been legal on the Iberian Peninsula and throughout much of the Mediterranean world. Southern European Christians and North African Muslims were locked in an ongoing struggle that fueled regional violence and generated large numbers of captive slaves. But what about the role played by those Europeans who claimed to be against slavery and who inhabited spaces where it was illegal? By the time Spain and Portugal were coursing up and down the coast of Africa and beginning the process of establishing colonies in the Americas, slavery was actually quite rare in northern Europe. Yet, eventually, every European nation embraced slavery as a part of their Atlantic endeavors. Clearly, some people actively embraced slavery even though they came from places that generally frowned upon the practice.

The English case is particularly instructive. From one perspective, it might appear as if the English had no intention of practicing slavery in the colonies they established after Jamestown in 1607. During the first few decades, there were hardly more than a few hundred Africans in places that would one day become part of the United States. Since slavery was not legal in England, we might be inclined to assume that English settlers in the colonies had neither the ability nor the inclination to implement a system of slavery in their colonies. Certainly, throughout the first half of the seventeenth century, there is little evidence to suggest that English colonists were intent on constructing New World slave societies that could come anywhere close to what existed in Latin America. For that reason, it once was common to describe the growth of slavery as either being accidental—an “unthinking decision” in the words of historian Winthrop Jordan—or a product of changes in the labor market that did not happen until the last few decades of the seventeenth century.

But there are other ways to characterize the English story that suggest that the English were quite eager to become slave traders and slave holders. Even before they established colonies, for example, the English bought and sold slaves in the Atlantic world. John Hawkins led three slave-trading expeditions and sponsored a fourth between Africa and Spanish America in the 1560s. English ships plundered enslaved African men and women by the hundreds from the Spanish and Portuguese. As far as northern Europeans were concerned, buying and selling, kidnapping and ransoming, and making the most of slavery before they had colonies was one of the potential benefits of maritime activity in the early modern era.

From that perspective, the story of 1619 and the arrival of the first Africans in Jamestown looks a bit different than the way the story is often told. It used to be suggested that the status of the first Africans in Virginia was unclear because the English had no law of slavery and no real experience with the practice as it existed in the Americas. While the former claim may be true, the latter claim is false. What the English didn’t have was a reliable supply chain, a problem they wouldn’t resolve until the second half of the seventeenth century when King Charles II chartered the Royal African Company. What they did have, however, was a rapacious appetite and willingness to treat vulnerable individuals with impunity. Illicit traders therefore found a ready market for African slaves who arrived in Virginia by the hundreds, and in places like Barbados by the thousands, before they formally legalized in 1661 what they had been doing all along.

The institution of slavery exploded throughout the Americas in the late seventeenth century, but it got a running start in the early modern Atlantic world. Europeans, eager to set themselves up as power brokers in the Atlantic world, extracted resources and exploited the Indigenous inhabitants of the Americas and sub-Saharan Africa to achieve their goals. Slavery facilitated the conquest of the Americas and fueled the development of plantation economies. The growth of slavery was aided by the crafting of racist justifications to explain why violence and human suffering on an unimaginable scale were not only acceptable but necessary. Fortunately, slavery was largely destroyed in the nineteenth century. Unfortunately, we continue to live in a world riven by its consequences.

Michael Guasco is chair and professor of history at Davidson College. He is the author of Slaves and Englishmen: Human Bondage in the Early Modern Atlantic World (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2014).