The Cubist Collage Aesthetic and the Historical Narratives of Jacob Lawrence

by Patricia Hills

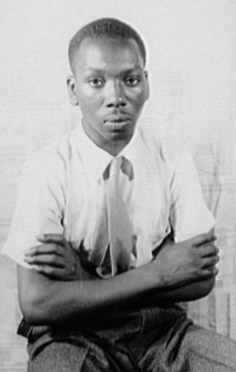

Jacob Lawrence stands as a giant in the field of American art. He was the first to devote himself to pictorializing the history of Black people in America—the heroes of struggle against slavery as well as ordinary people living within the confines of twentieth-century racism. He was also unique in creating a style of expressive collage cubism to convey the powerful messages of his paintings.

Jacob Lawrence stands as a giant in the field of American art. He was the first to devote himself to pictorializing the history of Black people in America—the heroes of struggle against slavery as well as ordinary people living within the confines of twentieth-century racism. He was also unique in creating a style of expressive collage cubism to convey the powerful messages of his paintings.

The cubist collage aesthetic would also seem especially fitting for an epic narrative focused not just on heroes and heroines, but on particularly important moments in the chronicle of a people. Although this aesthetic may be simple and reductive, it is also additive: overlapping shapes layered on the surface parallel the accumulation of incidents characteristic of an epic narrative. It is non-illusionistic: no tricks fool the eye, no felicities of chiaroscuro or cast shadows divert the spectator from the clarity of the story and the communication of its message. By eliminating illusionism Lawrence eliminated focus, texture, and, hence, the hierarchy of values that focus and texture entail. This lack of tonal values has its analogue in Lawrence’s aversion to personalizing the features of his heroes. To Lawrence these figures have importance as iconic embodiments of community and of social and political struggle.

In 1962 Lawrence delivered a speech, “The African Idiom in Modern Art,” in which he emphasized that cubism developed in Paris studios about 1900, after French artists discovered the masks and other artifacts of African art on display in anthropological museums. Lawrence’s response: “For here was an art both simple and complex—an art that possessed all of the qualities of the sophisticated community. It had strength without being brutal, sentiment without being sentimental, magic but not camouflage, and precision but not tightness.”[1] And in the same talk he praised the rationalism of the cubism that then developed: “Of all modernist concepts and styles, cubism has been the most influential. Because of its rationalism, its appeal has become universal. And because cubism seeks basic fundamental truths, it has enabled the artist to go beyond the superficial representation of nature to a more profound and philosophical interpretation of the material world.”[2]

A similar evaluation was made by the artist and gallerist Marius de Zayas in 1911, at the time when both he and Alfred Stieglitz were presenting African art in their New York galleries: “Picasso . . . receives a direct impression from external nature, he analyzes, he develops and translates it, and afterwards executes it in his own style, with the intention that the pictures should be the pictorial equivalent of the emotion produced by nature. In presenting his work he wants the spectator to look for the emotion or idea generated from the spectacle and not the spectacle itself.”[3] Although Lawrence probably never read de Zayas’s essay, he was familiar with Picasso—whose Guernica (1937) exemplified the horrors of the Spanish Civil War and which toured the country before its installation at the Museum of Modern Art.

Lawrence’s development as an artist prepared him for his style of expressive cubism. His parents were part of the Great Migration of Black Americans moving from the South to the North. Born in Atlantic City, New Jersey, in 1917, with his father, mother, and sister, he moved to Philadelphia. His parents then divorced, and his mother moved to Harlem. A few years later, when Lawrence was about nine years old, he and his sister moved to Harlem to join their mother once she had found a steady job.

Lawrence’s development as an artist prepared him for his style of expressive cubism. His parents were part of the Great Migration of Black Americans moving from the South to the North. Born in Atlantic City, New Jersey, in 1917, with his father, mother, and sister, he moved to Philadelphia. His parents then divorced, and his mother moved to Harlem. A few years later, when Lawrence was about nine years old, he and his sister moved to Harlem to join their mother once she had found a steady job.

Although he was never close to his mother, Lawrence admired her for using colored objects, rugs, and curtains to decorate their home—in fact he reflected that all the poor people’s homes in Harlem were awash in color. Color would become a major factor in his work. His mother also enrolled him in afterschool programs where he learned of the need to tell the stories of Black people.

Then, in the mid-1930s, when the federal government set up the Federal Art Project (FAP), which created community programs, Lawrence attended art classes at the Harlem Community Art Center. At first making designs for masks and small stage sets made of cardboard, he gravitated to Harlem artist Charles Alston, a graduate of Columbia University’s Teachers College, for instruction in art. Recognizing the young teenager’s talent, Alston steered Lawrence to develop his own style of flat shapes and compelling design.

Lawrence’s nonacademic method of conceiving pictures first as design structures would stay with him throughout his career. Early on he developed his signature style of working with descriptive lines, patterns of light and dark, and a limited palette of flat, unmodulated colors for composing pictures. When interviewers later asked him about his distinctive style, he would often say, “I didn’t think about it. It was all I could do. I couldn’t do anything else. I didn’t know of any other way to paint. So it wasn’t an intellectual process. . . . I was encouraged by various people. They didn’t try to change my style.”[4]

While he was learning to be an artist, he was also immersing himself in Black history by attending lectures and reading texts by progressive contemporary authors. An influential theorist of education at the time was another Columbia Teachers College teacher—John Dewey—author of the widely read Art as Experience (1934). Dewey and his followers believed that both the process of making art and the appreciation of art enriched the lives of individuals and, by extension, the community. In 1939 Holger Cahill, director of the FAP, delivered a tribute to Dewey at the philosopher’s eightieth birthday celebration: “John Dewey and his pupils and followers have been of the greatest importance in developing American resources in the arts, especially through their influence on the school systems of the country. They have emphasized the importance and pervasiveness of the aesthetic experience, the place of the arts as part of the significant life of an organized community, and the necessary unity of the arts with the activities, the objects, and the scenes of everyday life.”[5]

Lawrence did indeed paint scenes of everyday Harlem, but he became more ambitious. After having spent time in the Schomburg Library doing research on Black history and listening to lectures, he turned to painting multiple scenes focused on the epic histories of people who sought to free enslaved peoples: The Life of Toussaint L’Ouverture (1938), The Life of Frederick Douglass (1939), The Life of Harriet Tubman (1940), and in 1941 John Brown’s Arsenal and his sixty panels—The Migration of the Negro—depicting Blacks moving North beginning in 1914 to find jobs and escape the severe segregation of the racialized South (see And the Migrants Kept Coming).

Lawrence did indeed paint scenes of everyday Harlem, but he became more ambitious. After having spent time in the Schomburg Library doing research on Black history and listening to lectures, he turned to painting multiple scenes focused on the epic histories of people who sought to free enslaved peoples: The Life of Toussaint L’Ouverture (1938), The Life of Frederick Douglass (1939), The Life of Harriet Tubman (1940), and in 1941 John Brown’s Arsenal and his sixty panels—The Migration of the Negro—depicting Blacks moving North beginning in 1914 to find jobs and escape the severe segregation of the racialized South (see And the Migrants Kept Coming).

The pictures in each series show a variety of scenes and activities with captions drawn from Lawrence’s readings in history and the anecdotes from his Harlem neighbors about the Great Migration. In Harriet Tubman, we first see a scene of toiling enslaved Black people, with the caption from Harriet Tubman herself: “With sweat and toil and ignorance he consumes his life, to pour the earnings into channels from which he does not drink.” The second panel shows a lynched figure, with a caption that quotes the southern Senator Henry Clay defending slavery. Third comes a painting of a cotton plant with a passage from Abraham Lincoln’s famous 1858 speech that reads “A house divided against itself cannot stand.” Fourth is a panel showing carefree Black children tumbling in the landscape. The fifth panel shows Tubman lying on the ground and the disappearing legs of the overseer who has just beaten her. And so the series continues with a rhythm of images that suggests “cause and effect” but also the “call and response” traditions of the Black church (see Panel 9). Most of the captions draw from history. Some of the works seem very abstract—but they show, as De Zayas said, “the emotion or idea generated from the spectacle and not the spectacle itself.”

Lawrence’s other series show the same juxtapositions and rhythms in dialogue with concise and pithy quotations. The different series were well received, and Lawrence’s career was launched.

All through Lawrence’s life the operative word for humanity was “struggle.” In a 1982 lecture he said, “Man’s struggle is a very beautiful thing. . . . The struggle that we go through as human beings enables us to develop, to take on further dimension.”[6]

Lawrence led the way in joining an expressive cubism with Black history and with the humanistic goal to overcome adversity, build community, and create a better world.

Patricia Hills is professor emerita of art history at Boston University. Her books include Modern Art in the USA: Issues and Controversies of the Twentieth Century (Prentice Hall, 2001), May Stevens (Pomegranate Press, 2005), and Painting Harlem Modern: The Art of Jacob Lawrence (University of California Press, 2009; repr. 2019). She worked at the Whitney Museum (part time and full time) between 1971 and 1987, mounting such exhibitions as Eastman Johnson (1972) and John Singer Sargent (1986–1987). In 2011 she received the College Art Association award for Distinguished Teaching of Art History.

I want to thank the Gilder Lehrman Institute for providing me with a research grant in 2005 to do full-time research at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in Harlem.

[1] Jacob Lawrence, “The African Idiom in Modern Art” (1962), manuscript, p. 12, Box 3, Jacob Lawrence Archives, The George Arents Research Library, Syracuse University. Also available at the Archives of American Art.

[2] Jacob Lawrence, “The African Idiom in Modern Art” (1962), manuscript, p. 9.

[3] Marius de Zayas, “Picasso,” Camera Work (April–July 1911), pp. 65–67, quoted in Patricia Hills, “Jacob Lawrence’s Expressive Cubism,” in Ellen Harkins Wheat, Jacob Lawrence: American Painter (Seattle: Seattle Art Museum, 1986), p. 19.

[4] Jacob Lawrence, transcript of interview by Patricia Hills, May 20, 1985 (Patricia Hills archives).

[5] Excerpt from Holger Cahill, “American Resources in the Arts,” speech delivered in 1939 and quoted in Francis V. O’Connor, ed., Art for the Millions: Essays from the 1930s by Artists and Administrators of the WPA Federal Art Project (Boston: New York Graphic Society, 1973); also quoted in Patricia Hills, Painting Harlem Modern: The Art of Jacob Lawrence (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2009), p. 281.

[6] Jacob Lawrence, lecture delivered on November 15, 1982, quoted in Wheat, Jacob Lawrence: American Painter (1986), p. 105.