Citizenship in the Reconstruction South

by Susanna Lee

Slaveholders created a system of race, gender, and class inequality in the pre-Civil War South. They justified slavery by arguing that enslaved people could not take care of themselves and needed masters to look after them. White southern proslavery advocates compared slavery to marriage: masters supported their slaves, just as men supported their wives. Most white men excluded black men, black women, and white women from public affairs. Even non-elite white men—like non-slaveholders and other poor and middle-class southerners—found themselves in lesser positions. Elite slaveholding white men considered themselves best able to lead, and they dominated political offices. To differing extents, black men, black women, white women, and non-elite white men in the pre-Civil War South were subordinate members of the nation. The upheavals of the Civil War and Reconstruction brought opportunities to transform citizenship in the United States, determining who belonged to the nation, and what rights and privileges that membership conferred.

Initially, under President Andrew Johnson’s plan for Presidential Reconstruction, citizenship in the former Confederacy did not seem much changed. Johnson believed that former Confederates could be welcomed back into the nation even though they had rebelled against the United States. According to Johnson, the institution of slavery had created an aristocracy of slaveholders who controlled politics, and the destruction of the slaveholding class would “give more good citizens to the commonwealth.” [1] In contrast, Johnson could not imagine black southerners as good citizens, despite their many contributions to the Union cause during the Civil War. He believed that black southerners possessed less “capacity for government than any other race of people” and that “wherever they have been left to their own devices they have shown a constant tendency to relapse into barbarism.” As a result, Johnson insisted that only white men could lead the South, and he made no provisions for the participation of black people in restoring the South to the Union. [2] Johnson pardoned former Confederates for their rebellion, and many returned to political office during Presidential Reconstruction.

Initially, under President Andrew Johnson’s plan for Presidential Reconstruction, citizenship in the former Confederacy did not seem much changed. Johnson believed that former Confederates could be welcomed back into the nation even though they had rebelled against the United States. According to Johnson, the institution of slavery had created an aristocracy of slaveholders who controlled politics, and the destruction of the slaveholding class would “give more good citizens to the commonwealth.” [1] In contrast, Johnson could not imagine black southerners as good citizens, despite their many contributions to the Union cause during the Civil War. He believed that black southerners possessed less “capacity for government than any other race of people” and that “wherever they have been left to their own devices they have shown a constant tendency to relapse into barbarism.” As a result, Johnson insisted that only white men could lead the South, and he made no provisions for the participation of black people in restoring the South to the Union. [2] Johnson pardoned former Confederates for their rebellion, and many returned to political office during Presidential Reconstruction.

Black southerners, once considered least capable of acting as good citizens before the Civil War, transformed the idea and practice of citizenship during Reconstruction. Before the Civil War, most white people thought that black people, because of their supposed racial inferiority or because of the degradation of slavery, could not govern themselves as free people, let alone others as voters or officeholders. During the Civil War, black people proved the opposite, offering their support for the Union cause by the thousands. Black men made one of the greatest sacrifices for their nation—fighting and dying on the battlefield—even before that nation officially recognized them as citizens.

Under Presidential Reconstruction, former slaveholders tried to reassert their control over their former slaves in many ways: by terrorizing and assaulting them, forcing them into involuntary labor, restricting their freedom of movement, and limiting their economic independence. Black southerners refused to accept the freedom-in-name-only offered by their former masters and mistresses. They petitioned, protested, and fought for the dignities, rights, and privileges of citizenship in the nation. At a freedmen’s convention in Virginia in August 1865, leaders of the African American community criticized Presidential Reconstruction:

We, the undersigned members of a Convention of colored citizens of the State of Virginia, would respectfully represent that, although we have been held as slaves, and denied all recognition as a constituent of your nationality for almost the entire period of the duration of your Government, and that by your permission we have been denied either home or country, and deprived of the dearest rights of human nature: yet when you and our immediate oppressors met in deadly conflict upon the field of battle—the one to destroy and the other to save your Government and nationality, we, with scarce an exception, in our inmost souls espoused your cause, and watched, and prayed, and waited, and labored for your success. . . .

When the contest waxed long, and the result hung doubtfully, you appealed to us for help, and how well we answered is written in the rosters of the two hundred thousand colored troops now enrolled in your service; and as to our undying devotion to your cause, let the uniform acclamation of escaped prisoners, “whenever we saw a black face we felt sure of a friend,” answer.

Well, the war is over, the rebellion is “put down,” and we are declared free! Four fifths of our enemies are paroled or amnestied, and the other fifth are being pardoned, and the President has, in his efforts at the reconstruction of the civil government of the States, late in rebellion, left us entirely at the mercy of these subjugated but unconverted rebels, in everything save the privilege of bringing us, our wives and little ones, to the auction block. . . .

We know these men—know them well—and we assure you that, with the majority of them, loyalty is only “lip deep,” and that their professions of loyalty are used as a cover to the cherished design of getting restored to their former relations with the Federal Government, and then, by all sorts of “unfriendly legislation,” to render the freedom you have given us more intolerable than the slavery they intended for us. [3]

Black southerners had served their nation during the Civil War, and they called on the federal government to protect them during Reconstruction.

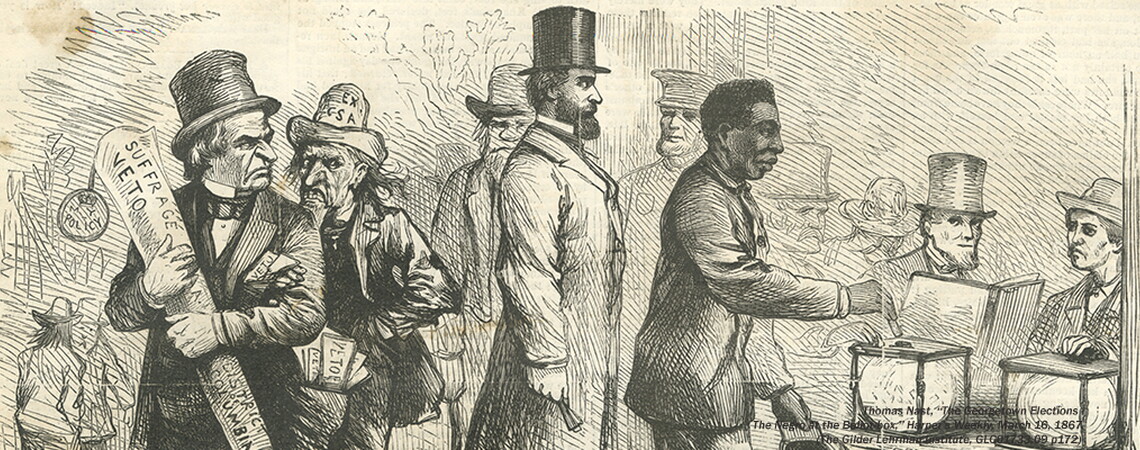

Black people’s efforts to fight the re-imposition of white supremacy by former slaveholders and to publicize attacks on black and white Unionists prompted congressional Republicans to take steps to protect freedoms in the South during a period called Congressional Reconstruction. They provided for a new process, one very different from Presidential Reconstruction, in which black and white men who had been loyal to the Union during the Civil War formed new state governments in the South. Congressional Republicans considered stripping former Confederates of their citizenship, but settled for prohibiting them from participating in forming the new state governments. During Congressional Reconstruction, the United States officially granted citizenship and rights to black people. The Fourteenth Amendment, passed in 1866 and ratified in 1868, established birthright citizenship and prohibited states from abridging the privileges and immunities of citizenship. The Fifteenth Amendment, passed in 1869 and ratified in 1870, prohibited states from denying citizens the right to vote on account of race, but not sex. The establishment of birthright citizenship—that people born in the United States, regardless of race, possessed the rights and privileges of citizenship—corrected what many Republicans saw as the unjust decision in Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857), that black people could not claim citizenship and that they had “no rights which the white man was bound to respect.” The Reconstruction Amendments and other Reconstruction measures were powerful and unprecedented efforts by the federal government to define and protect citizens, especially those newly freed from slavery.

During Congressional Reconstruction, black southerners allied with white southerners, especially those who had previously held little political or economic power. Through the Republican Party, black and white southerners acted as citizens in an unprecedented interracial alliance that brought democratic reforms to the South, especially greater rights and protections to everyday folk, those whose humble standing or racial status had previously marked them for discrimination. New state constitutions drafted during Congressional Reconstruction established state-funded systems of public education and other government institutions for common people, abolished property-holding qualifications for office-holding and jury service, prohibited imprisonment for debt, and exempted homesteads and other personal property from seizure by creditors.

White women outside the South, drawing on Congressional Reconstruction’s egalitarian promise, called for the expansion of women’s rights as citizens, especially their political and economic rights. White women in the South did not form a comparable women’s rights movement. Regardless, efforts to enfranchise women in the Reconstruction Amendments failed. In addition, none of the new state constitutions written under Congressional Reconstruction provided for female suffrage. Constitutional conventions in Texas, North Carolina, and Arkansas considered but ultimately rejected women’s suffrage. [4] Women’s rights activists did succeed in securing some economic rights. Most wives had no legal identity separate from their husbands, which prevented them from owning property or controlling their own wages. State legislators passed laws after the Civil War that allowed married women to hold their own property. However, southern legislators passed these married women’s property acts primarily as a way to shield the husbands’ property from creditors, not as a women’s rights reform. [5] The failure of women’s suffrage and the conservative nature of married women’s property acts in the South suggest the larger opposition of many white southerners to the transformations of Congressional Reconstruction.

Many former Confederates, especially former slaveholders, organized themselves into the Conservative or Democratic Party and opposed Congressional Reconstruction, often violently. They embraced terrorism in the form of groups like the Ku Klux Klan who intimidated and murdered black and white Republicans. Federal officials withdrew support for Congressional Reconstruction, distracted by other concerns. The end of Congressional Reconstruction limited the ways that many black and white southerners could act out their citizenship in the South. However, the Reconstruction Amendments—incorporated into the Constitution in part through black activism in the South—remained. New generations of black and white southerners would draw on Congressional Reconstruction for inspiration and the Reconstruction Amendments for constitutional authority in their struggles to claim full citizenship in the nation.

[1] Dan T. Carter, When the War Was Over: The Failure of Self-Reconstruction in the South, 1865−1867 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1985), 29−30.

[2] Andrew Johnson, Annual message to Congress, December 1867, quoted in Eric Foner, Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863−1877 (New York: Harper & Row, 1988), 179−181.

[3] “An Address, To the Loyal Citizens and Congress of the United States of America,” printed in Liberty, and Equality before the Law. Proceedings of the Convention of the Colored People of VA., Held in the City of Alexandria, Aug. 2, 3, 4, 5, 1865 (Alexandria, VA: Cowing & Gillis, 1865), p. 21; “The Late Convention of Colored Men,” New York Times, August 13, 1865.

[4] Elna C. Green, Southern Strategies: Southern Women and the Woman Suffrage Question (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1997), 6–7.

[5] Suzanne Lebsock, “Radical Reconstruction and the Property Rights of Southern Women,” Journal of Southern History 43, no. 2 (May 1977): 195–216.

Susanna Lee teaches the history of the American Civil War and Reconstruction at North Carolina State University. She earned her BA in history at the University of California, San Diego, and her MA and PhD in history from the University of Virginia. Her book, Claiming the Union (Cambridge University Press, 2014), focuses on southern citizenship after the Civil War. She is currently working on a book about the US–Dakota War.