An Arduous Path: The Passage and Ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment

by Elaine Weiss

As we mark the centennial of women’s constitutional right to vote, we should remember that the Nineteenth Amendment, like the suffrage movement itself, was forced to navigate an arduous path. Even at the endgame, even at the dawn of the second decade of the twentieth century, the idea of women holding the ballot was still controversial and contested, the final skirmishes were grueling and bitter, and the success of the amendment was in grave doubt until the very last moment.

As we mark the centennial of women’s constitutional right to vote, we should remember that the Nineteenth Amendment, like the suffrage movement itself, was forced to navigate an arduous path. Even at the endgame, even at the dawn of the second decade of the twentieth century, the idea of women holding the ballot was still controversial and contested, the final skirmishes were grueling and bitter, and the success of the amendment was in grave doubt until the very last moment.

When Congress finally passed the amendment in June 1919—after stalling for forty years, and after voting it down twenty-eight times in committee or on the floor of the House or Senate—the suffragists knew that they did not have the luxury of celebrating for more than a few moments. The next stage of the fight—for ratification in each of the forty-eight states—needed to begin immediately. Winning congressional passage had been tough, a constant effort since the amendment’s introduction in 1878, but winning ratification would be even tougher.

During the four decades of delay in Congress the suffragists worked on a parallel track in the states, trying to change state laws that restricted the franchise to men. They conducted scores of campaigns in the states to put woman suffrage on the agendas of state constitutional conventions, on legislative dockets, and on the ballot of popular referenda—where, of course, only men could vote to decide whether women “deserved” the franchise. Woman suffrage was voted down in most of these referenda; the proposition was successful in a handful of states, mostly in the West.

It was painfully obvious that some states would never grant the vote to their women citizens—not just the southern states, but also Massachusetts, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Ohio, all of which had already rejected suffrage referenda. The only solution was a federal amendment that would supersede state voting restrictions affecting the women of every state.

Suffrage leaders disagreed on the best way to push the amendment through Congress. Beginning in 1916 Carrie Catt and the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) pursued their “Winning Plan” strategy, which sought suffrage referendum victories in a few populous states to achieve a critical mass of support, forcing Congress to consider the political consequences of opposition to the amendment. When New York women won the vote by referendum in 1917, pressure on Congress increased.

Alice Paul and her National Woman’s Party took a very different approach. Forget state campaigns, they insisted, and concentrate on pressuring Congress and the President to support the amendment, employing confrontational tactics if necessary. They campaigned to defeat candidates who did not support the amendment, and attempted to punish the party in power (in this case, Democrats, who controlled both the White House and Congress) for inaction, even if that meant working against legislators who’d long been staunch advocates of women’s right to vote. This strategy did not win many friends.

Both NAWSA and the NWP set up extensive lobbying operations in Washington, with resident staff supplemented by grassroots suffragists from every state imported to lobby their own congressmen and senators. Both groups maintained detailed files on each legislator, and deployed their knowledge of his political sore spots to help “convince” him.

The suffrage organizations took very different approaches toward swaying President Woodrow Wilson. Catt courted him, extending invitations, visiting the White House, and engaging emissaries to speak privately with the President. When America entered the European conflict in spring 1917, Catt set aside her own pacifist principles to support the war effort, pledging the work of the women of NAWSA on the home front in an effort to prove the patriotism of suffragists and strengthen their call for the vote.

The suffrage organizations took very different approaches toward swaying President Woodrow Wilson. Catt courted him, extending invitations, visiting the White House, and engaging emissaries to speak privately with the President. When America entered the European conflict in spring 1917, Catt set aside her own pacifist principles to support the war effort, pledging the work of the women of NAWSA on the home front in an effort to prove the patriotism of suffragists and strengthen their call for the vote.

Alice Paul (a Quaker) and the NWP denounced the war, and began picketing the White House, accusing the President of hypocrisy for waging a war “to make the world safe for democracy” while denying half of the citizens of the US a voice in their own democracy. They held picket banners reading “Democracy Begins at Home” and even “Kaiser Wilson.” They burned the President’s words in bonfires at the White House gates. They were arrested on bogus charges—like obstructing the sidewalk—jailed, kept in vermin-infested cells, physically assaulted, and force-fed with tubes rammed down their noses. The NWP’s actions were considered unpatriotic in wartime, and NAWSA suffragists denounced these protest tactics. But the NWP did garner lots of press attention, and even won sympathizers and admirers among the public.

All this put pressure on Congress to move on the amendment. The House approved the amendment in January 1918, but the Senate refused. Party politics, racism (the Nineteenth Amendment would extend the vote to black women), and the wishes of corporate backers (who believed women voting would be bad for the bottom line) combined with fears for their own re-election bids and old-fashioned misogyny to give senators ample reason to oppose the amendment.

In the fall of 1918, with the war still raging (but just weeks before the Armistice) Wilson did something no president had ever done: he stood—in person—before Congress and urged the Senate to approve the federal woman suffrage amendment, saying that women deserved the vote, and women’s support was a “spiritual instrument” he needed to conduct the war.

The Senate humiliated him, voting down the amendment the next day. They defeated the amendment again in February 1919, just when Wilson was headed to Paris to negotiate an end to the war and propose his idea for lasting peace, the League of Nations. Congress also opposed joining the League. Wilson determined that his only chance to pressure Congress into accepting American entry into the League was to allow American women—who tended to support peaceful resolutions rather than war—vote in the 1920 elections. He became an outspoken champion for the federal amendment and its ratification, though he was sidelined during much of the ratification process by a devastating stroke. During his incapacitation, the White House was secretly run by his wife Edith—an avowed anti-suffragist.

The Senate finally relented in June 1919, but even the final Senate debates included calls for insidious alterations to the amendment: one to allow states to enforce the law “as they saw fit” and another inserting the word “white” to define the women citizens entitled to vote. The amendment squeaked through, winning the approval of the required two-thirds of senators—but only by the margin of a few votes.

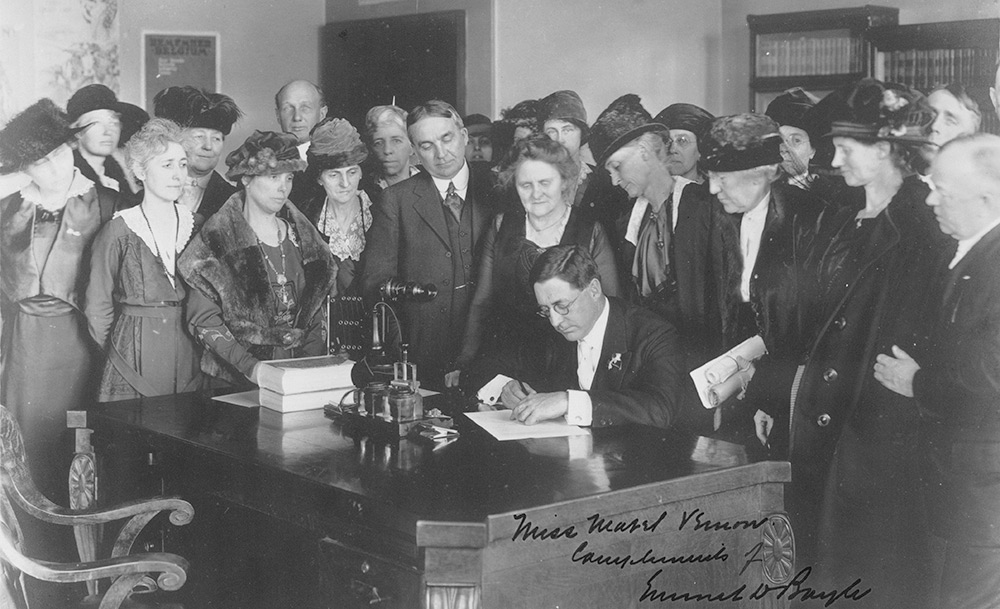

Following congressional passage on June 4, the amendment was transmitted to the states, where three-fourths, or thirty-six states of the forty-eight then in the union, were required for ratification.

The amendment’s journey through the states was made more difficult, purposefully so, by the Senate’s delay: they released it for ratification at a time when most state legislatures were not in session, and many met only every two years, or for a limited stretch each year. This required the extra step of governors calling their legislators to the capital for an “extraordinary session,” which many governors resisted doing on account of bother, expense, and political peril. (A few governors feared their legislatures might impeach them if convened.) So suffragists had to convince the governors of thirty states to call special sessions before they could even begin convincing legislators to ratify.

Both wings of the US suffrage movement—NAWSA and the NWP—immediately launched their ratification plans, mobilizing their members in every state to press their governors to call a special session of the legislature, then bombarding legislators with personal pleas to support ratification.

The first days of the ratification process in early June 1919 were easy and gratifying for the suffragists. Michigan, Illinois, and Wisconsin raced to claim the honor of first state to ratify; Wisconsin even sent its certification of ratification on a fast train, delivered by hand to the secretary of state in Washington DC. In a late-night special session, New York whisked its ratification through both houses of the legislature in less than three hours. Minnesota’s legislators stood and sang the “Battle Hymn of the Republic” in celebration of their ratification. Members of the Pennsylvania House of Representatives in Harrisburg also burst into patriotic song when the amendment passed in their chamber.

Utah, where women had enjoyed the vote since 1896, approved the amendment unanimously, with an assemblywoman presiding over the quick, decisive roll call in the lower house. Ohio suffragists celebrated their legislature’s ratification at a saloon—toasting their success with Prohibition-compliant lemonade. But even as they celebrated, Ohio opponents of the Nineteenth Amendment were busy circulating petitions to recall the ratification.

Within the first three months—through the summer of 1919—seventeen states ratified the amendment. But by fall, the pace slowed and trouble began. Many governors refused to call special sessions. Most galling to the suffragists was the delay of the governors of the western states, where women already enjoyed the right to vote, to convene their legislators to ratify. Carrie Catt called them “selfish” and conducted a whistle-stop tour of the western states to confront the governors and rally support for the amendment. Alice Paul and her staff were also busy in the field, pushing for state action, lobbying for ratification, even escorting reluctant legislators into the chambers to vote.

They met considerable pushback. The governor of Louisiana tried to organize a block of thirteen of his fellow southern governors to pledge to refuse special sessions, and failing that, to work to kill ratification in their states. Such orchestration was hardly necessary; almost all of the southern states enthusiastically rejected the amendment, on the basis of states’ rights and the importance of denying African American women the vote.

In the north, the governor of Connecticut adamantly refused to call a special session. Suffragists organized a “Flying Emergency Corps” of distinguished women from every state to swoop into Connecticut, holding rallies and marches and town hall lectures across the state, then confronting the governor in his office to argue for ratification. He refused. The governors of Vermont and Florida were equally stubborn.

Suffragists were alarmed by how difficult, and how close, the ratification vote in New Jersey proved to be. They were shocked when moderate Delaware rejected the amendment. Even as ratification was won in some statehouses, anti-suffrage lawyers immediately challenged the decision, petitioning for recalls and reversals.

By the spring of 1920, the suffragists had eked out thirty-five state ratifications, one shy of the threshold for ratification and entry into the Constitution. Only one more state was needed, but options were few: nine states had rejected the amendment, one (North Carolina) was poised to reject it, and three states were refusing to convene their legislatures to consider it. That left only Tennessee as a possible thirty-sixth state. The suffragists knew Tennessee was a dangerous place to stage what might be the final fight for the fate of the amendment, and they had good reason to worry.

The Tennessee suffragists were fractious. The Tennessee governor did not want to deal with the amendment; he was unpopular and had a re-election primary fight on his hands. Both the governor and the Tennessee legislature tried to avoid the issue, claiming they were bound by a Reconstruction-era provision in the state constitution that prohibited their considering a federal amendment before an election. But when the Supreme Court ruled that such provisions were unconstitutional, Tennessee ran out of excuses, and the governor was forced to call legislators to Nashville to deal with the amendment.

The newspapers would come to call these weeks in Nashville “the war of the roses” as Nineteenth Amendment supporters wore yellow roses on breast and lapel, while opponents wore red roses. They also called it “Suffrage Armageddon” as the fight turned bitter and wild.

Realizing how crucial the battle in Tennessee would be, Carrie Catt came to Nashville for six weeks to direct campaign strategy; Alice Paul sent her top lieutenants and organizers. The two rival suffrage camps set up separate headquarters and operated with separate staffs toward their mutual goal. They faced intense opposition not only from hostile politicians and powerful corporate interests (the railroad, textile manufacturers, and liquor lobbies especially), but also from wary clergymen, who railed against woman suffrage from the pulpit.

But the most emotional opposition to the amendment came from anti-suffrage women. Tennessee “antis” converged on Nashville, together with contingents from the other southern states, and national leaders from Boston, New York, and Washington. They warned that woman suffrage would endanger the American family, undermine Christian values and the southern way of life, and bring about the moral collapse of the nation. Their arguments devolved into a blatant racist appeal: The Nineteenth Amendment would grant the vote to black women, which would upset southern social norms.

The situation in Nashville was complicated by the fall presidential elections, and the candidates were reluctantly dragged into the fray. President Wilson dispatched missives from the White House. Once the legislature met in session, the city was swarming with corporate lobbyists, political operatives, journalists, and suffrage and anti-suffrage campaigners, all trying to influence the beleaguered legislators. A nasty political battle ensued: there was bribery and booze, propaganda and blackmail, fistfights and kidnappings. Legislators who had pledged to support the amendment began to mysteriously change their minds. Suffragists despaired, and it looked like they were going to lose.

On the last day of deliberations, the fate of the amendment was decided by a single vote of conscience, from the youngest member of the legislature, twenty-four-year-old delegate Harry T. Burn, who had received a note from his mother that morning. Heeding her plea, he changed his vote to break a tie in the House, tipping the tally to ratification. Even after the vote, anti-suffrage forces tried to nullify the proceedings, using parliamentary and legal maneuvers, court injunctions, and incendiary public protest rallies to “Save the South.” Despite all this, the Nineteenth Amendment officially entered the US Constitution on August 26, 1920. In celebration, church bells rang across the country.

Even then, opponents of the amendment did not give up their fight, taking their argument all the way to the Supreme Court; the Court finally dismissed their claims in 1922. The promise of the Nineteenth Amendment would be denied to many African American women in the southern states by the same Jim Crow laws that had already subverted the Fifteenth Amendment, robbing black men of their voting rights. Poll taxes, literacy tests, intimidation, and violence would make a mockery of these constitutional voting rights, which were not enforced by the states—or by Congress—until the voting Rights Act of 1965.

Selected Bibliography

Catt, Carrie Chapman, and Nettie Shuler. Woman Suffrage and Politics: The Inner Story of the Suffrage Movement . New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1923. New edition forthcoming from Dover Publications, 2020.

Harper, Ida Husted, History of Woman Suffrage, vol. 6, 1900−1920. New York: National American Woman Suffrage Association, 1922.

Weiss, Elaine. The Woman’s Hour: The Great Fight to Win the Vote. New York: Viking/Penguin, 2018.

Wheeler, Marjorie Spruill, Votes for Women! The Woman Suffrage Movement in Tennessee, the South, and the Nation. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1993. New edition forthcoming, 2020.

Elaine Weiss is an award-winning journalist and writer. Her magazine features have been recognized with prizes from the Society of Professional Journalists, and her writings have appeared in The Atlantic, Harper’s, the New York Times, the Boston Globe, and the Philadelphia Inquirer. She is the author of The Woman’s Hour: The Great Fight to Win the Vote (Viking, 2018).